Kishine Barracks and the 106th General Hospital

Life and death in the Vietnam War medical communications zone in Japan

By William Wetherall

First posted 18 December 2015

Last updated 2 June 2024

Kishine and the 106th

Purpose

•

Sources

•

Memory

•

Fact checking

•

Editing

•

Corrections

•

Abbreviations

•

Japanese terms

2017 Kanagawa News article

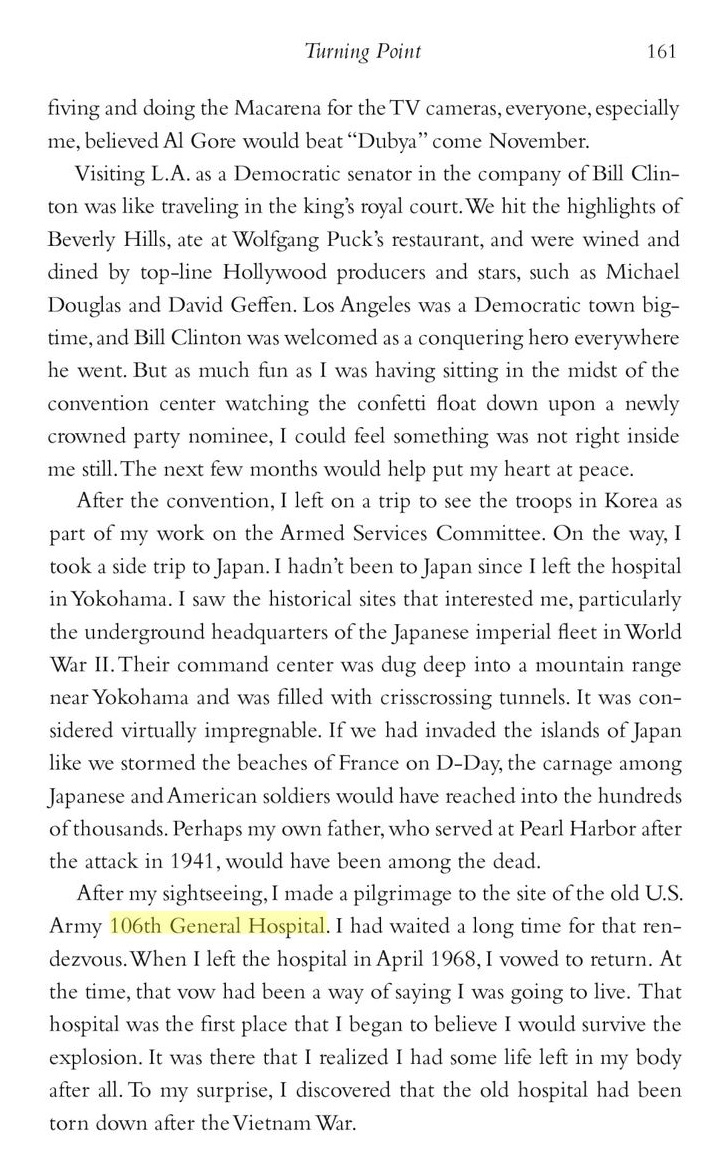

106th General Hospital (1969)

Unit history

•

Installation

•

Mission

•

Officers

•

Organization

•

Operation

•

Hospitalization

•

Burns

•

Personnel

•

Map

•

Buildings

•

Photographs

106th in Stars and Stripes

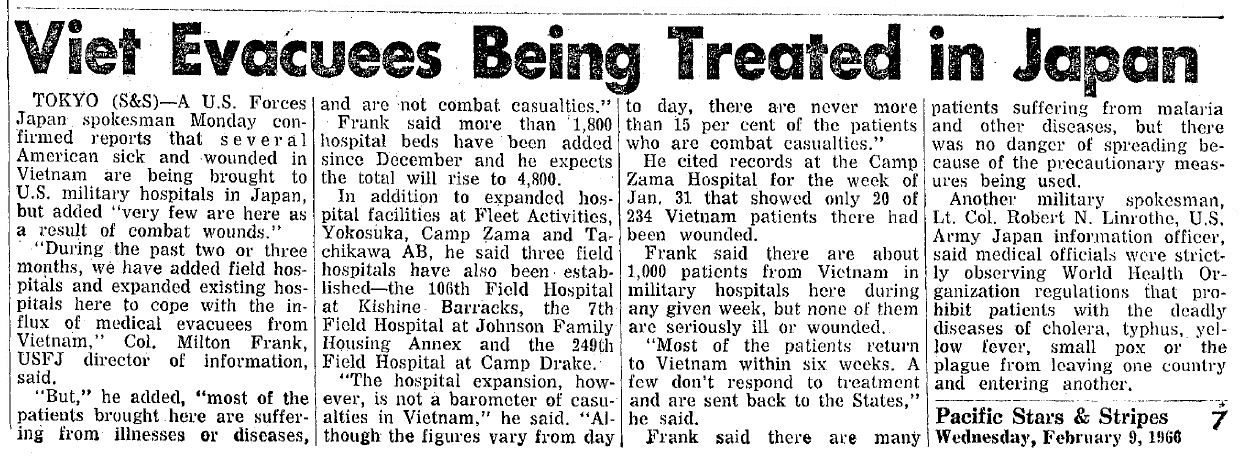

Viet evacuees

•

Hospitals

•

Doctors

•

Nurses

•

Other staff

•

Patients

•

Medals and awards

•

Red Cross

•

Sports

•

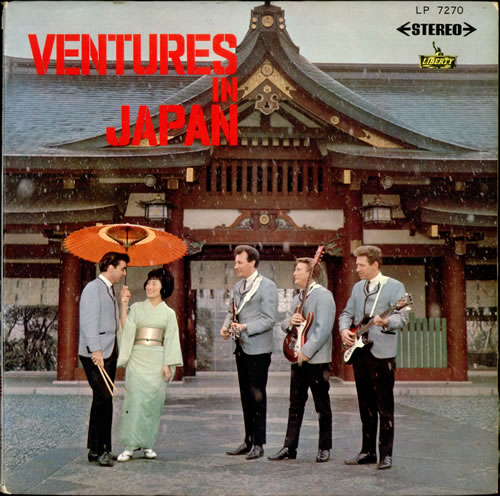

Celebrities

•

Milieu

106th medical reports

Abdominal injuries

•

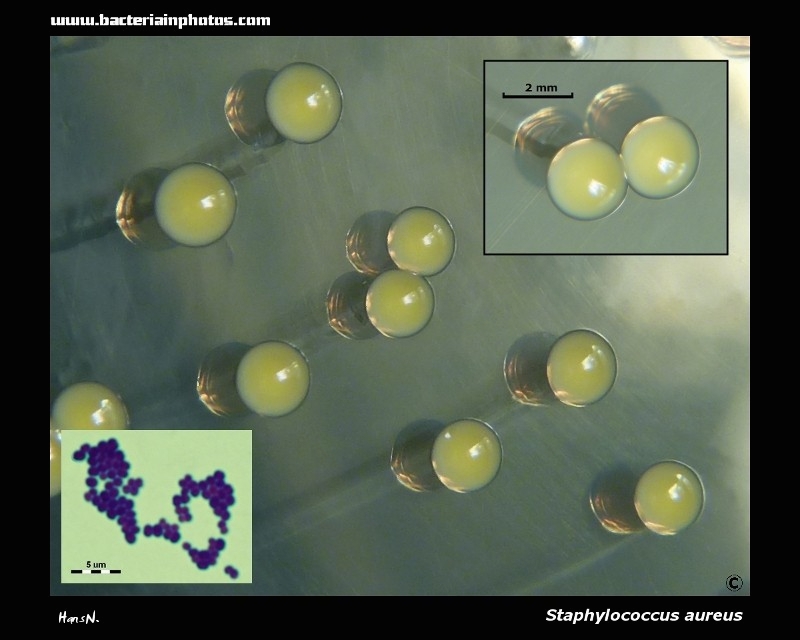

Bacteria in wounds

•

Bacteremia

•

Burns report

•

Fat embolism

•

Pulmonary insufficiency

•

Septic phlebitis

•

Vascular injuries

•

Amputations

•

Head wounds

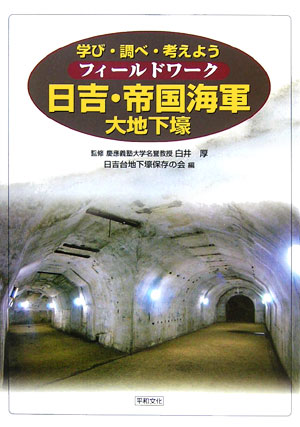

Kishine history

Aerial photos

•

Geography

•

Before wars

•

China and Pacific Wars

•

Allied Occupation

•

Post-Occupation

•

Vietnam War

•

Renovations

•

Reversion

•

Kishine Park

Kishine images

Then and now

•

Photos

•

Suido street

•

Area maps

•

Satellite views

•

Street views

Park access

Park guides

Park vs Barracks

Kishine stories

Tales by or about some of the people who were there for whatever reason

Other stories

PTSD appellants

•

MUC claims

•

Reunion

•

Wheeler

•

Zengaku

•

Air crashes

•

SDF sub-camp

•

Tower jumper

Other hospitals

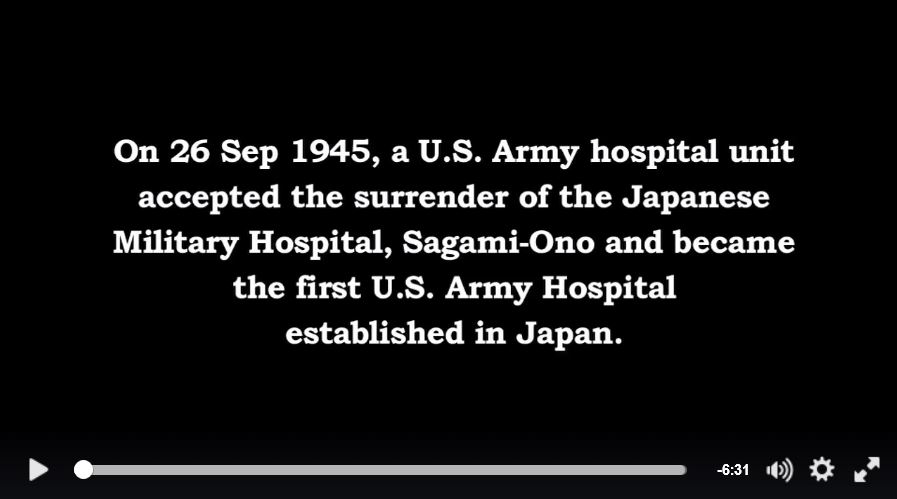

Sagami-Ono Hospital

•

7th Field Hospital

•

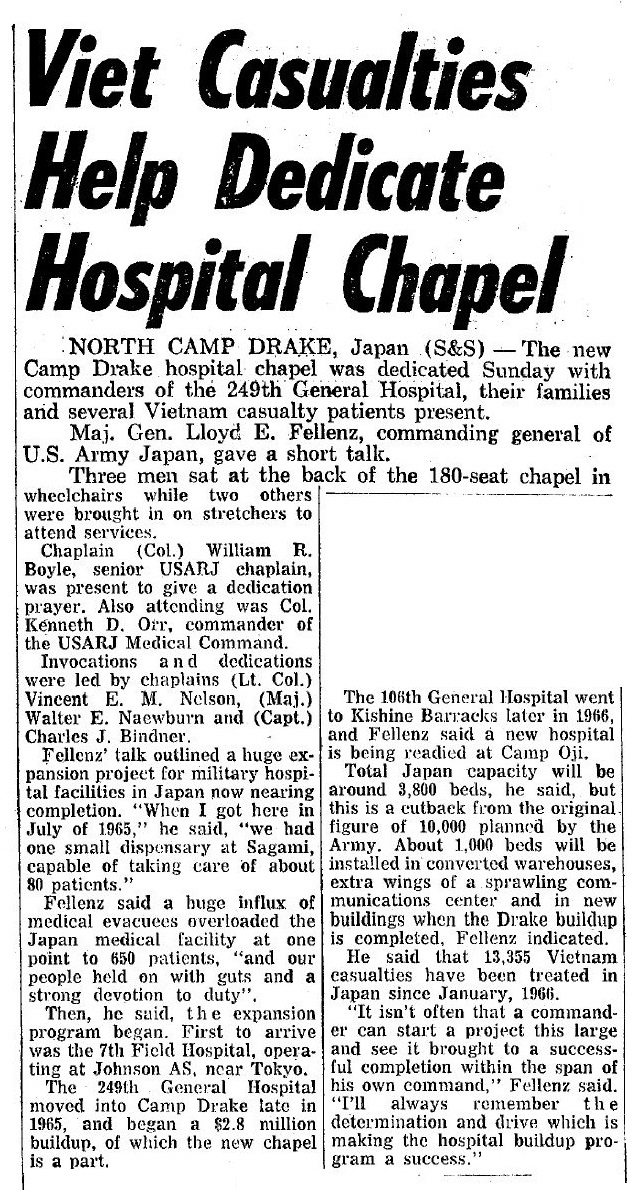

249th General Hospital

•

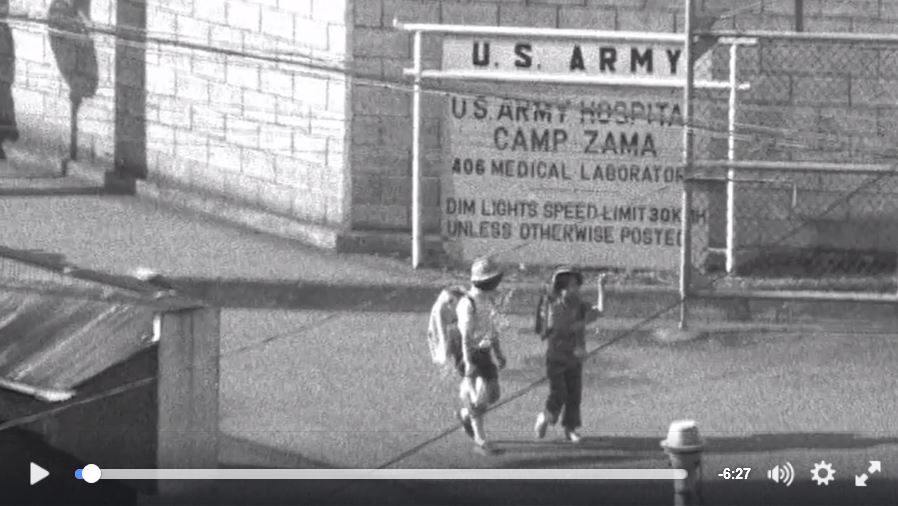

406th Medical Laboratory

•

Hospitals in Vietnam

•

Evacuation

Other perspectives

Marriages

•

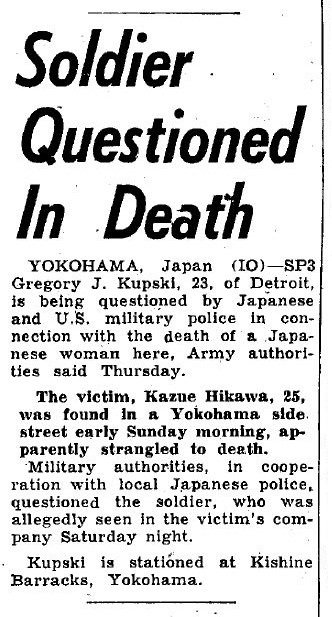

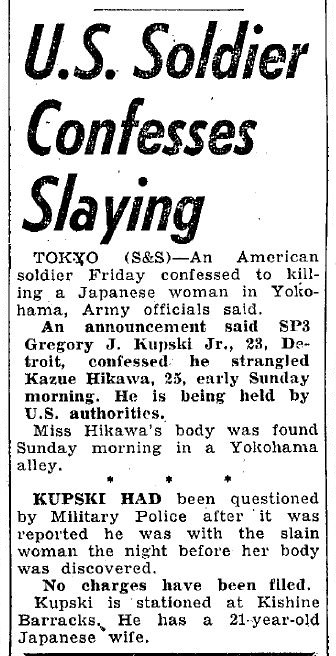

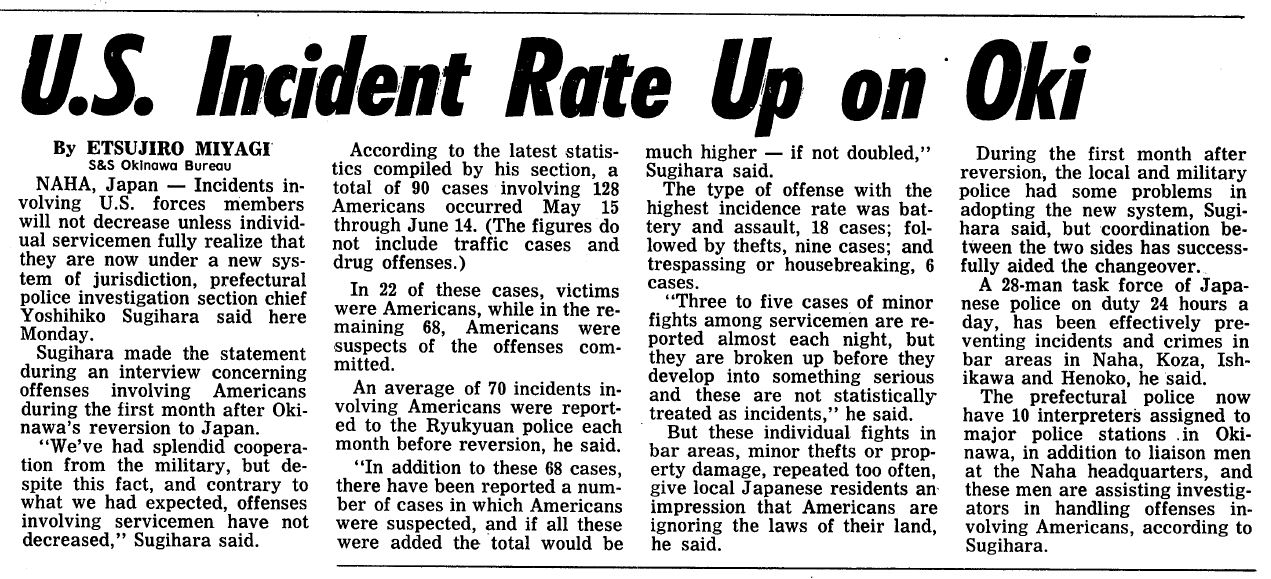

Crime

•

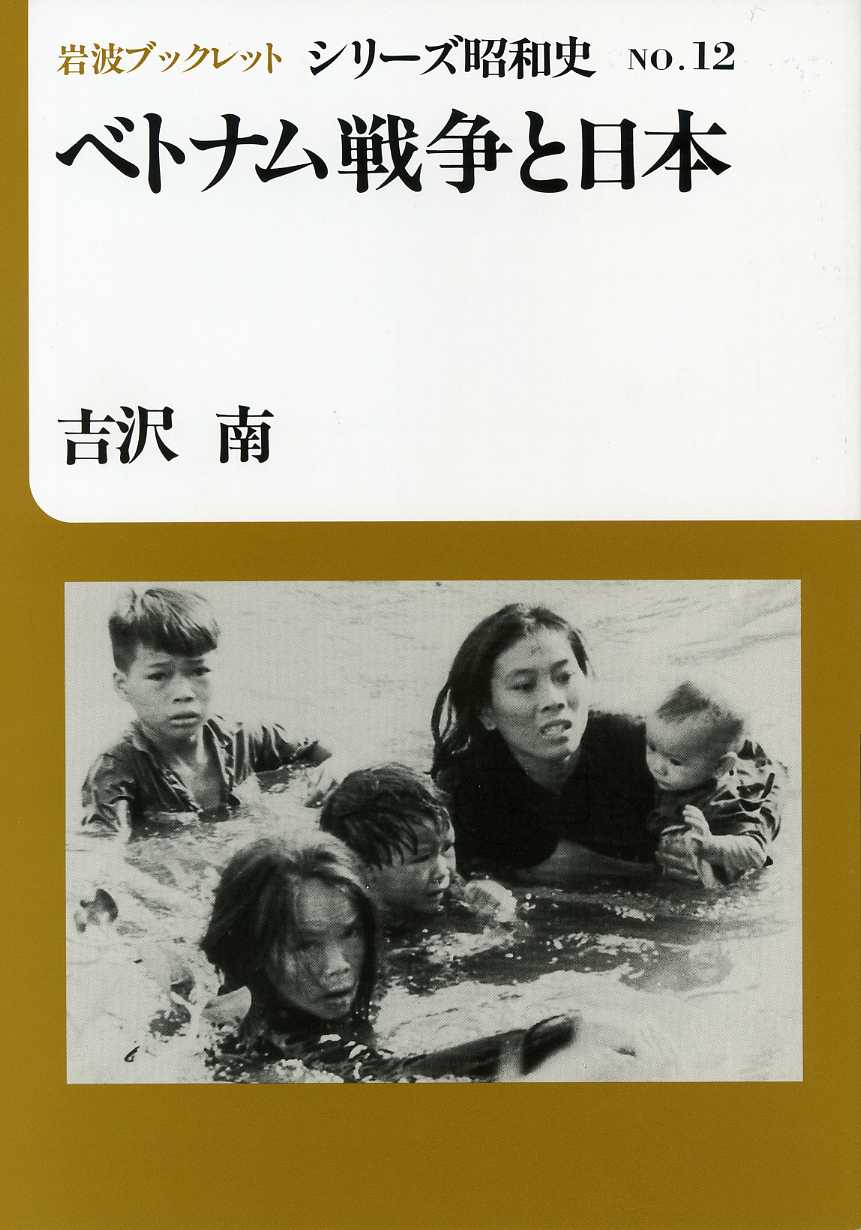

Vietnam and Japan

•

Rest & Recuperation

•

Helicopters

•

Community protests

•

Urban legends

•

Demonstrations

•

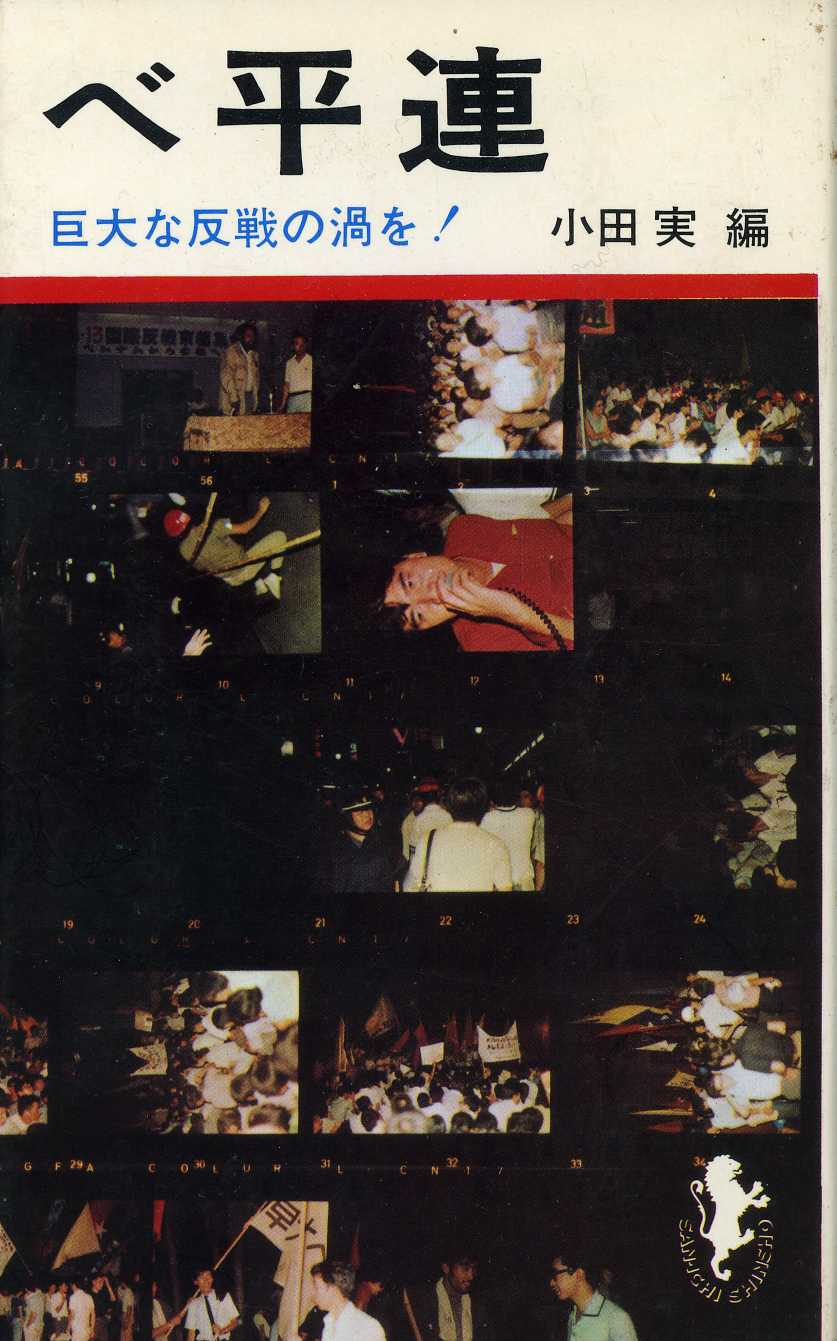

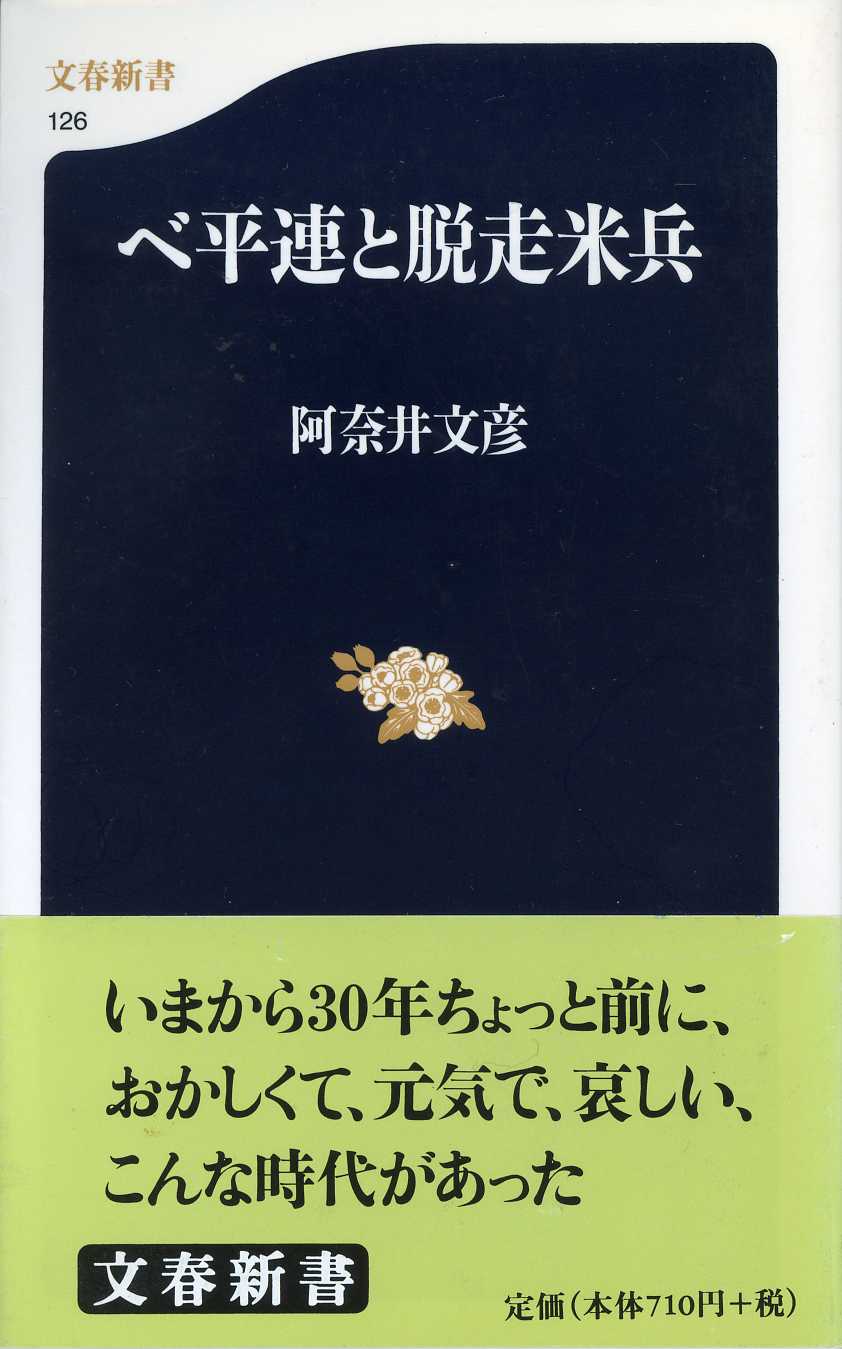

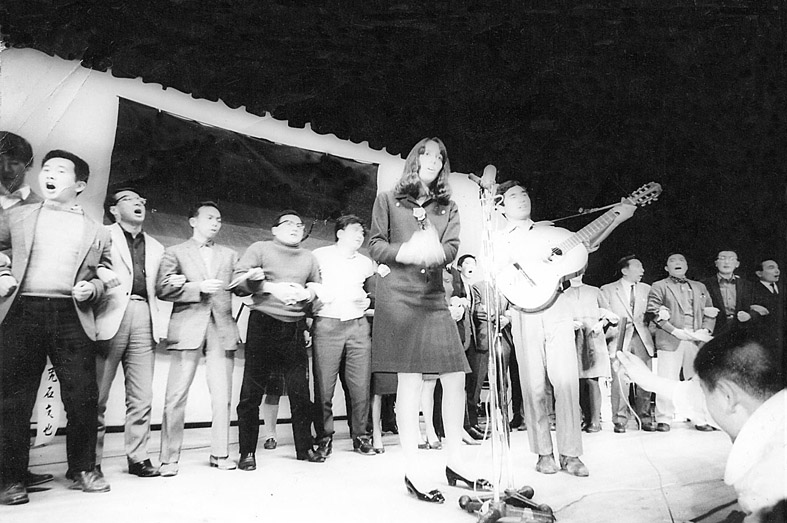

Beheiren

Other directions

Veterans on desertion

•

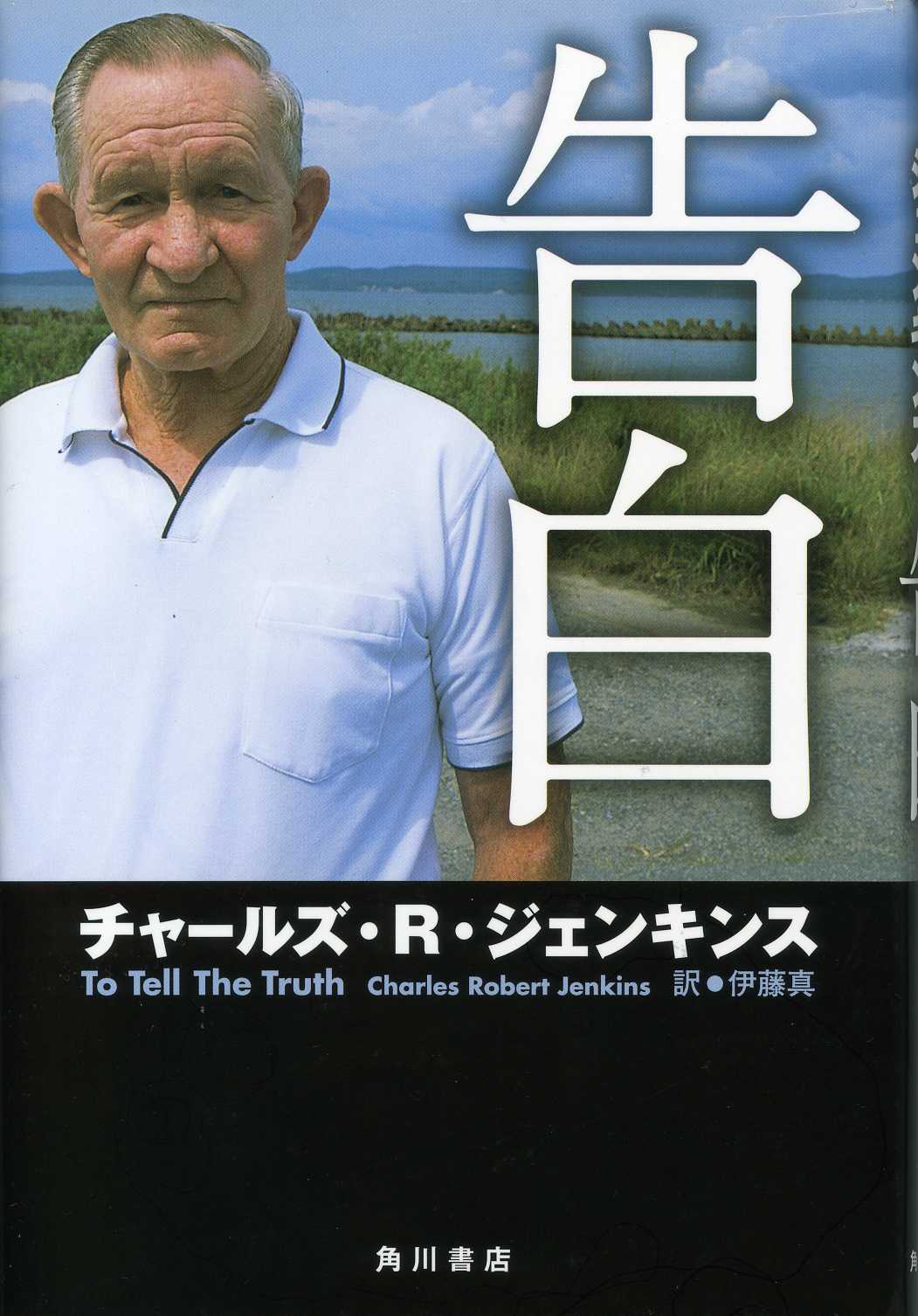

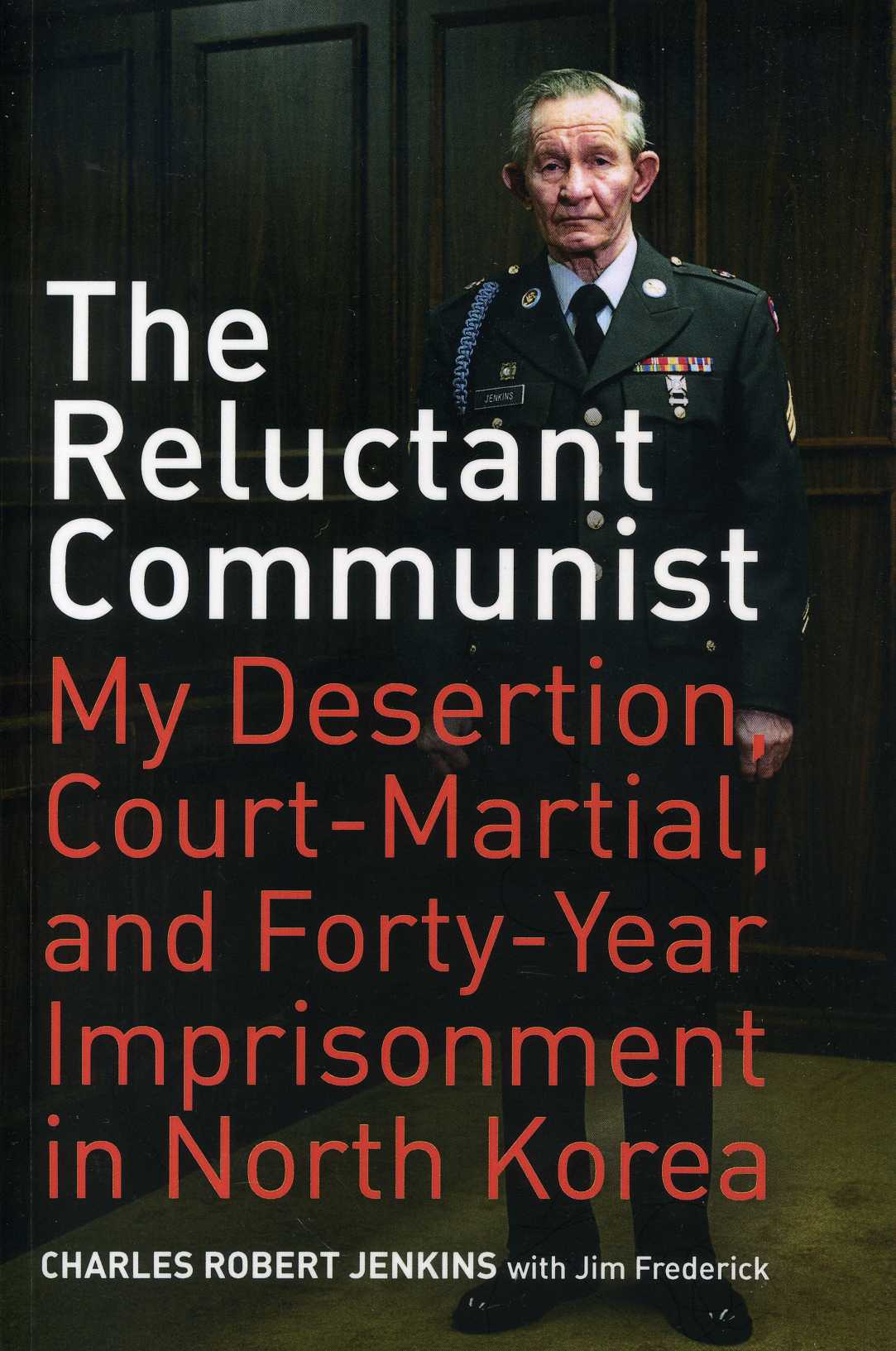

Charles Jenkins

•

Kim Tonghui and Kim Hyungsung

•

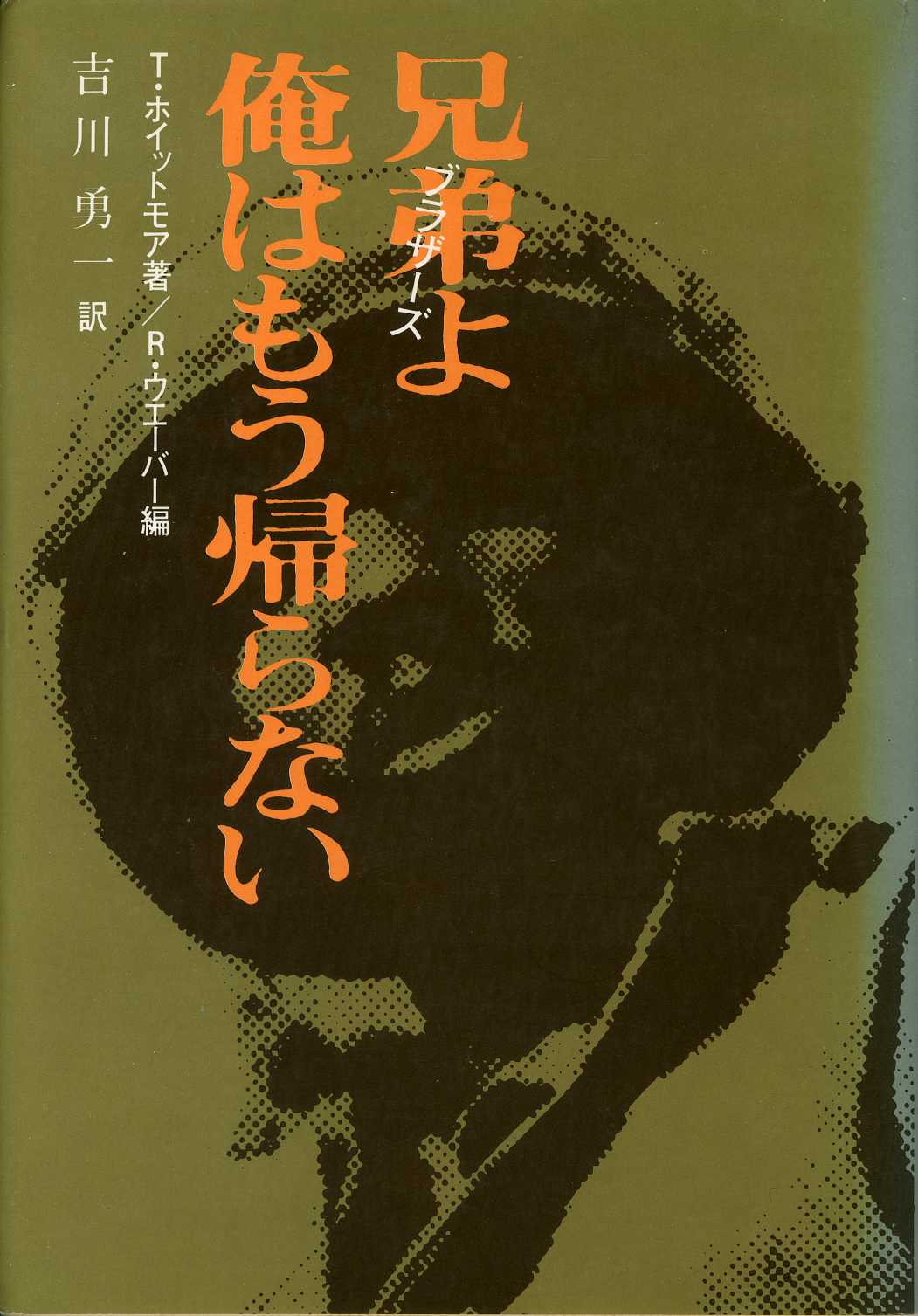

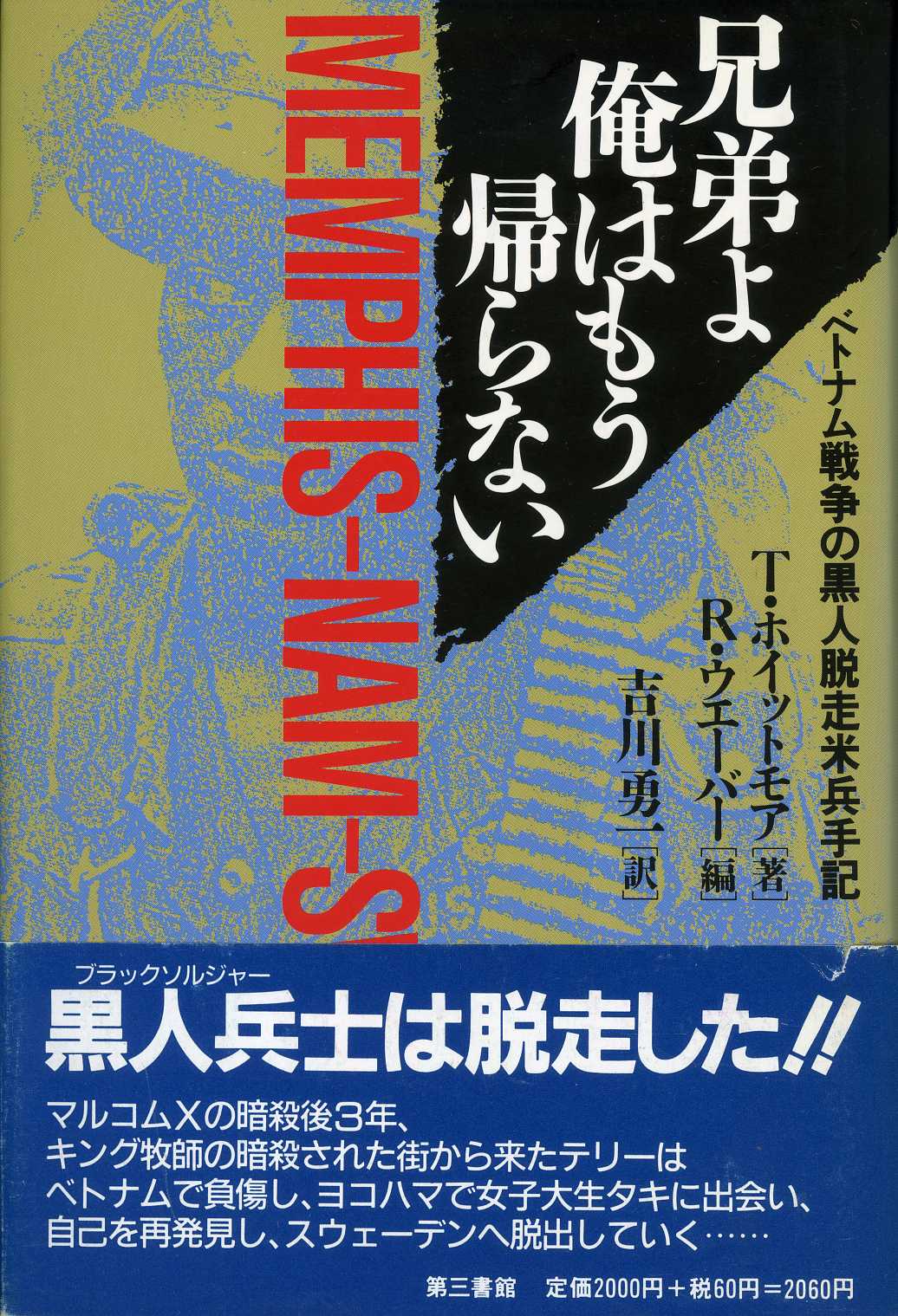

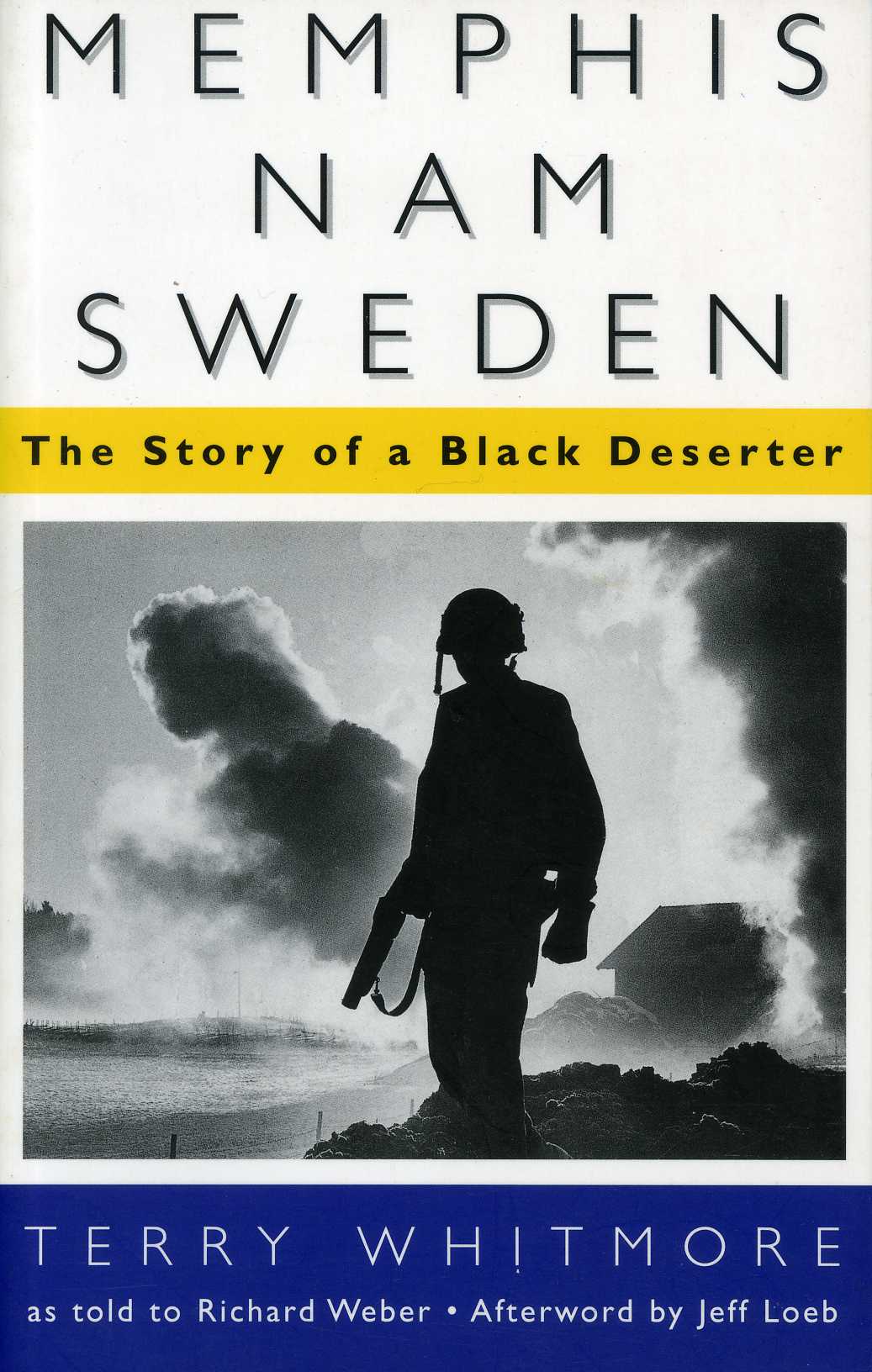

Terry Whitmore

•

Kenneth Briggs aka Kim Jinsu

•

Shimizu Tetsuo

Early posts and training

Basic training (Ft. Ord)

•

Medical corpsman training (Ft. Sam Houston)

•

561st Ambulance Company (Ft. Ord)

•

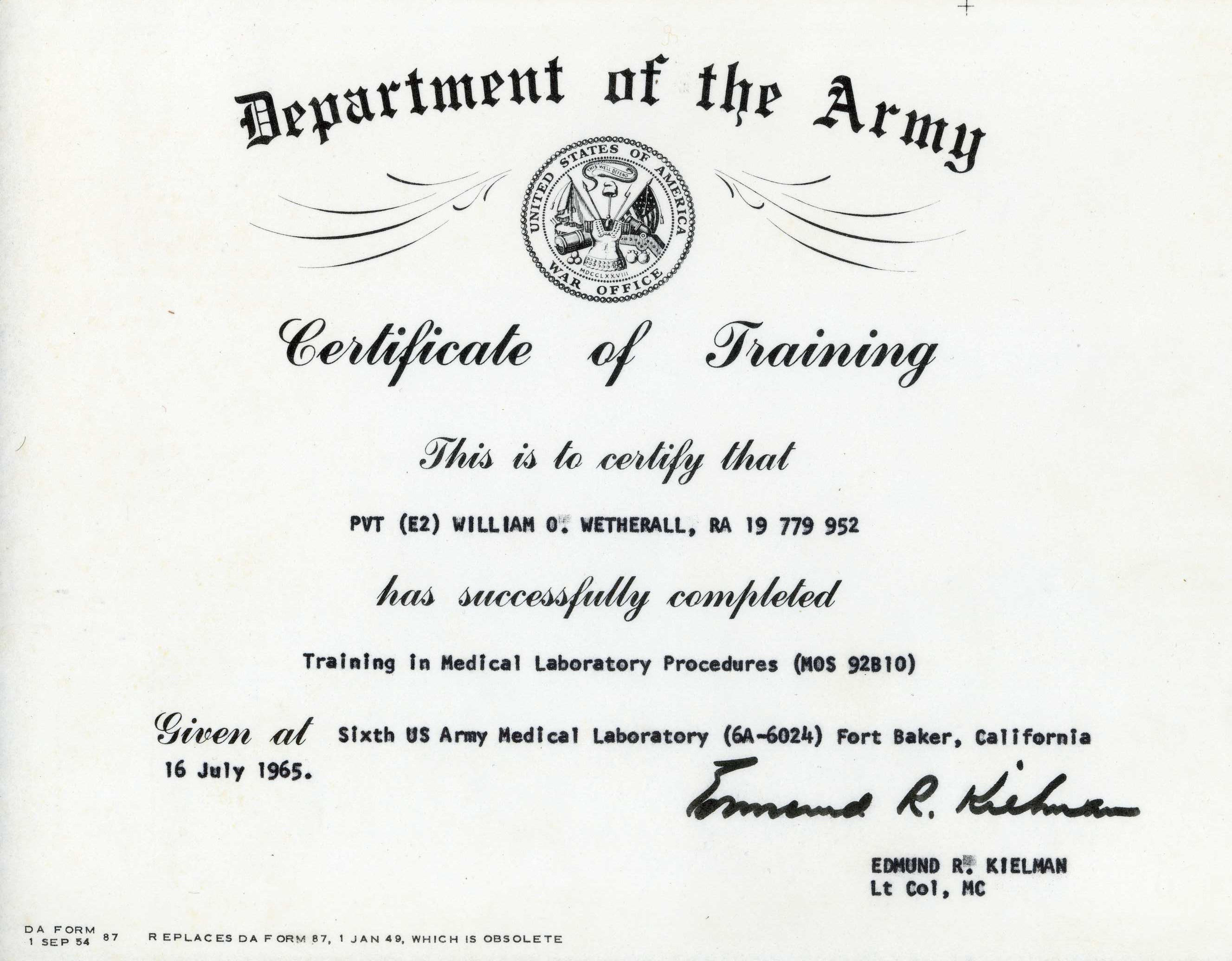

Lab tech training (Ft. Baker)

Lab tech posts

USAH (Ft. Ord)

•

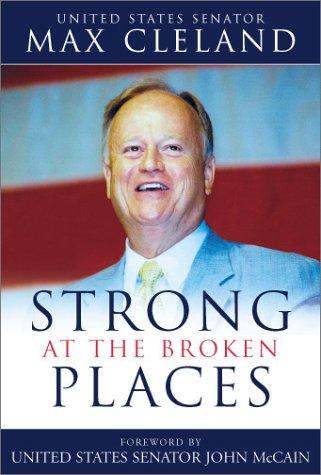

106th General Hospital (WBGH Ft. Bliss)

•

McAfee Army Hospital (WSMR)

•

106th General Hospital (Kishine Barracks)

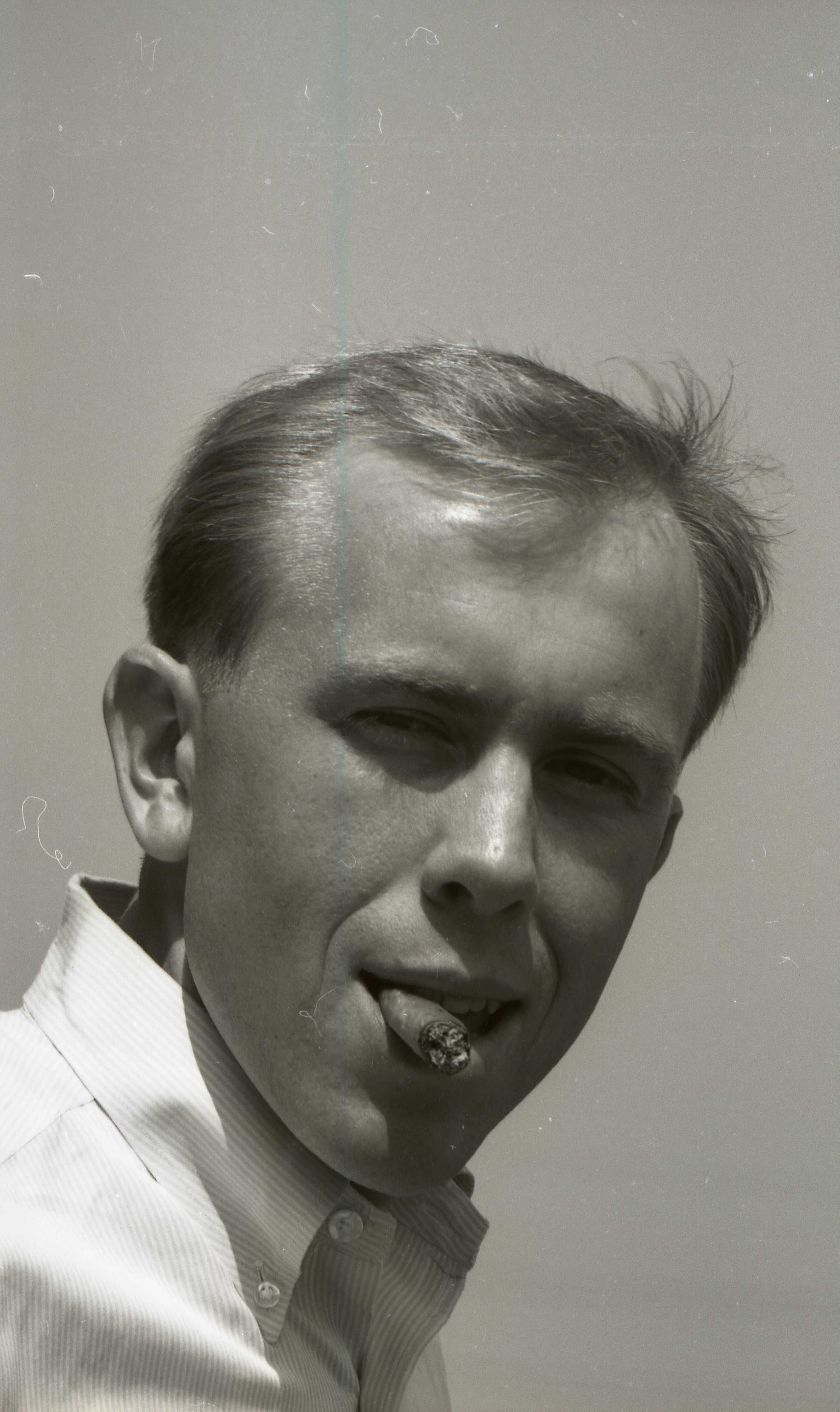

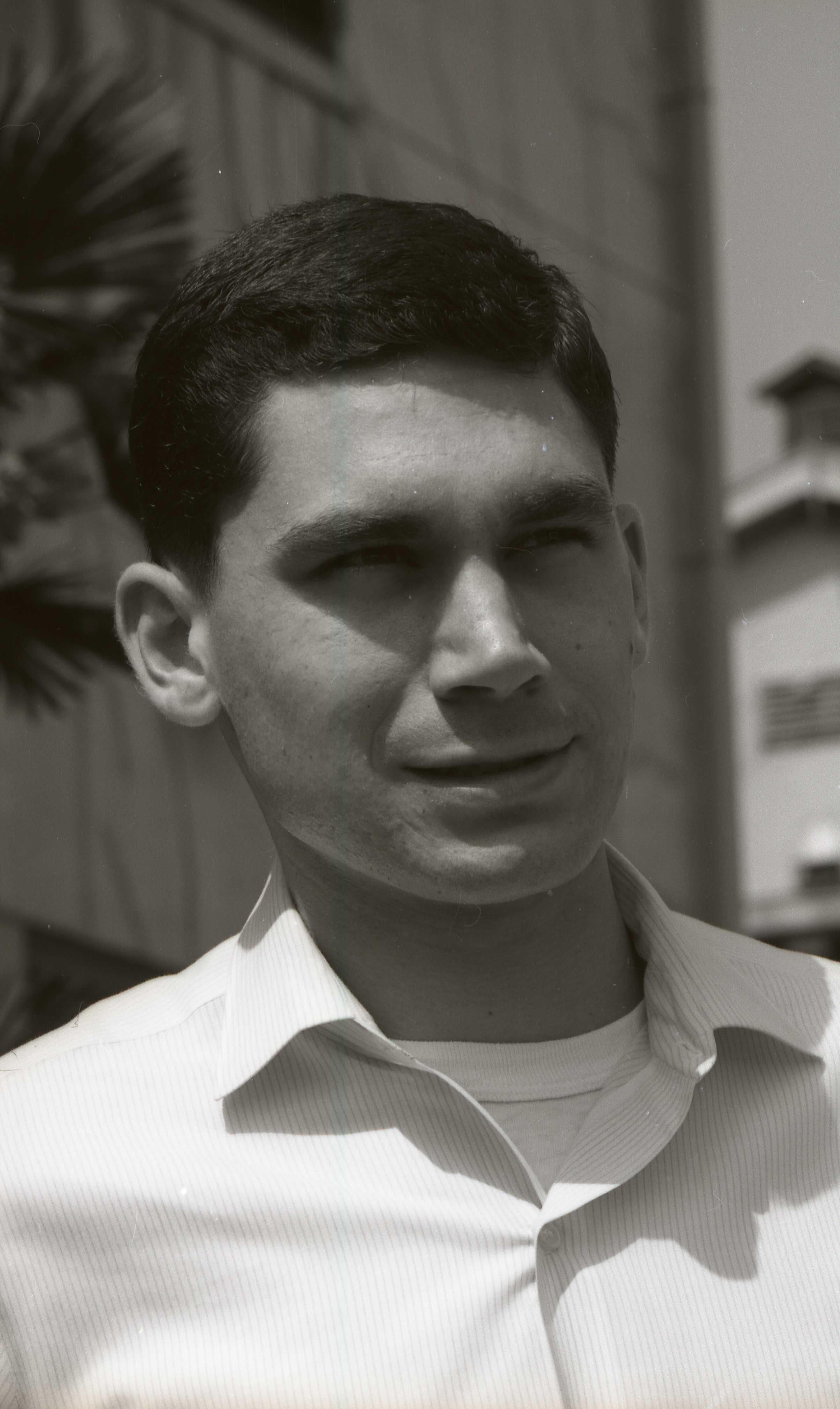

People I knew

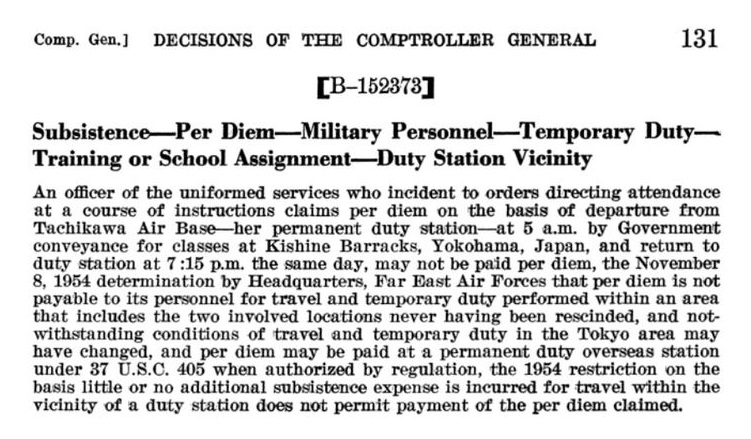

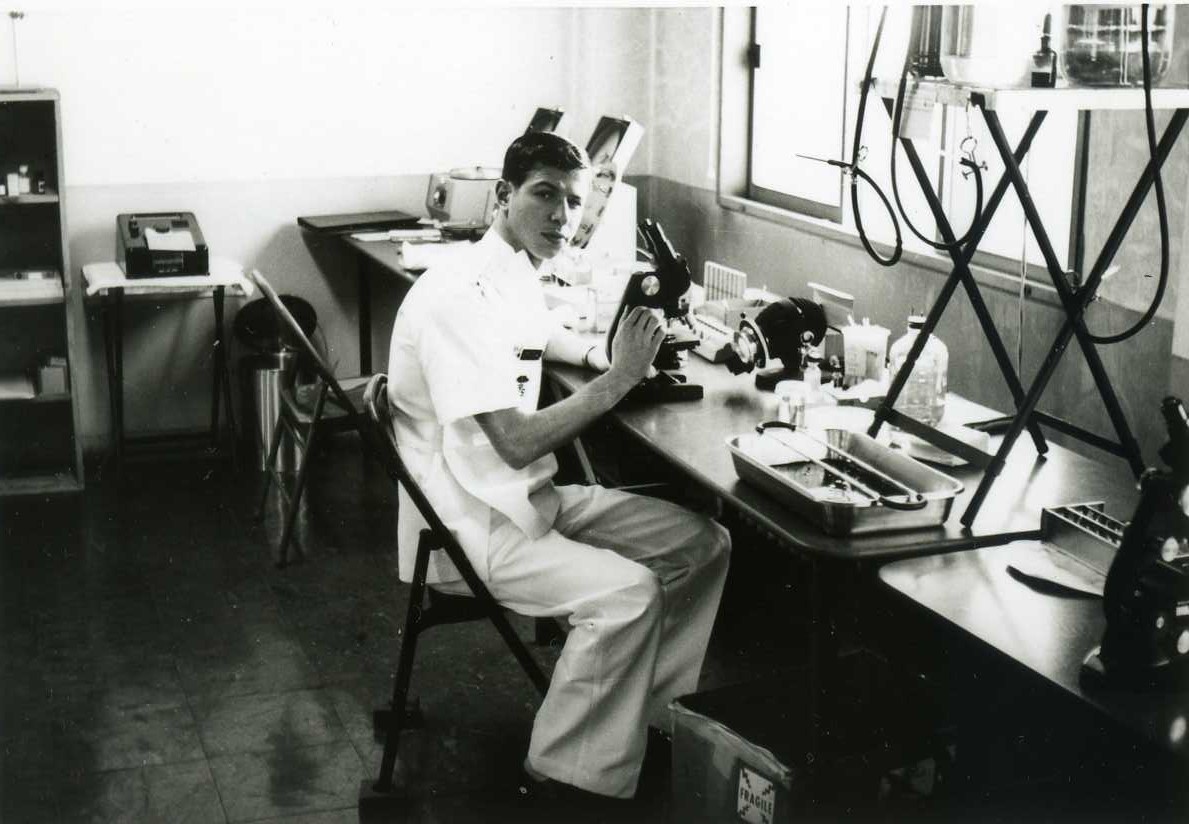

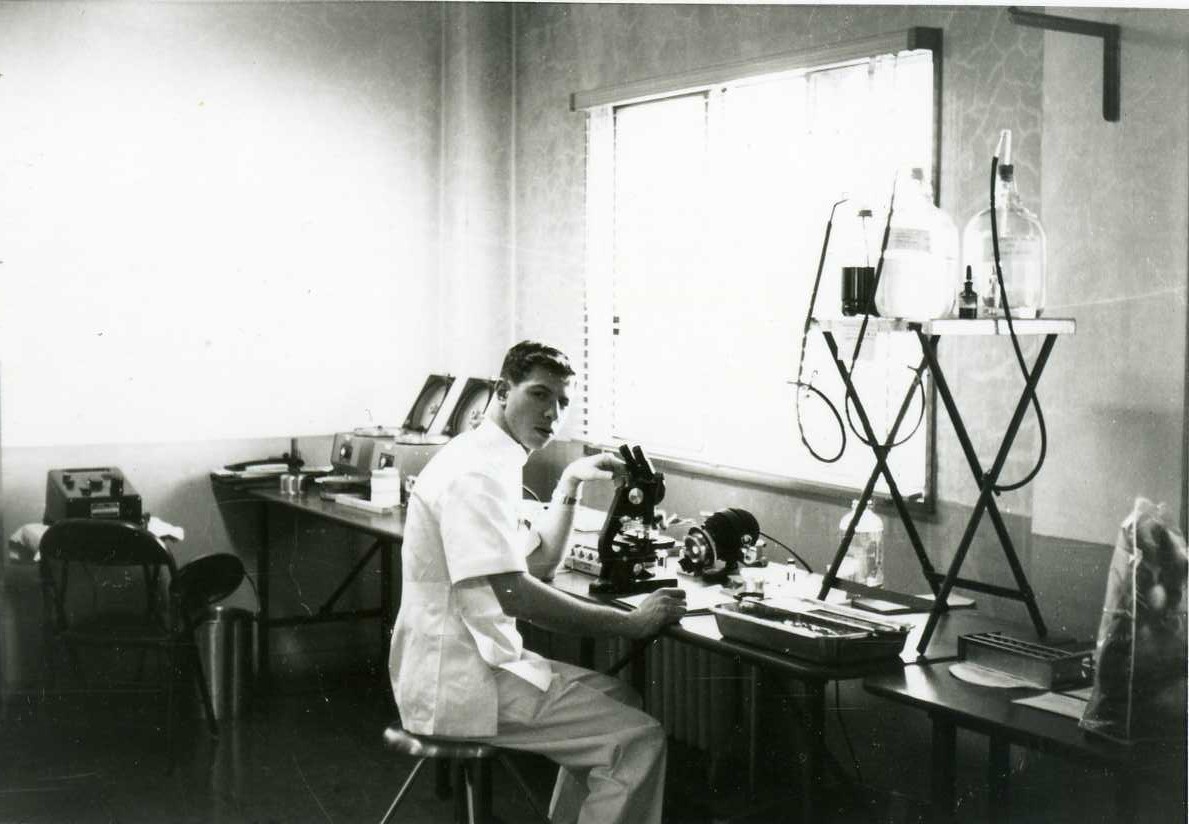

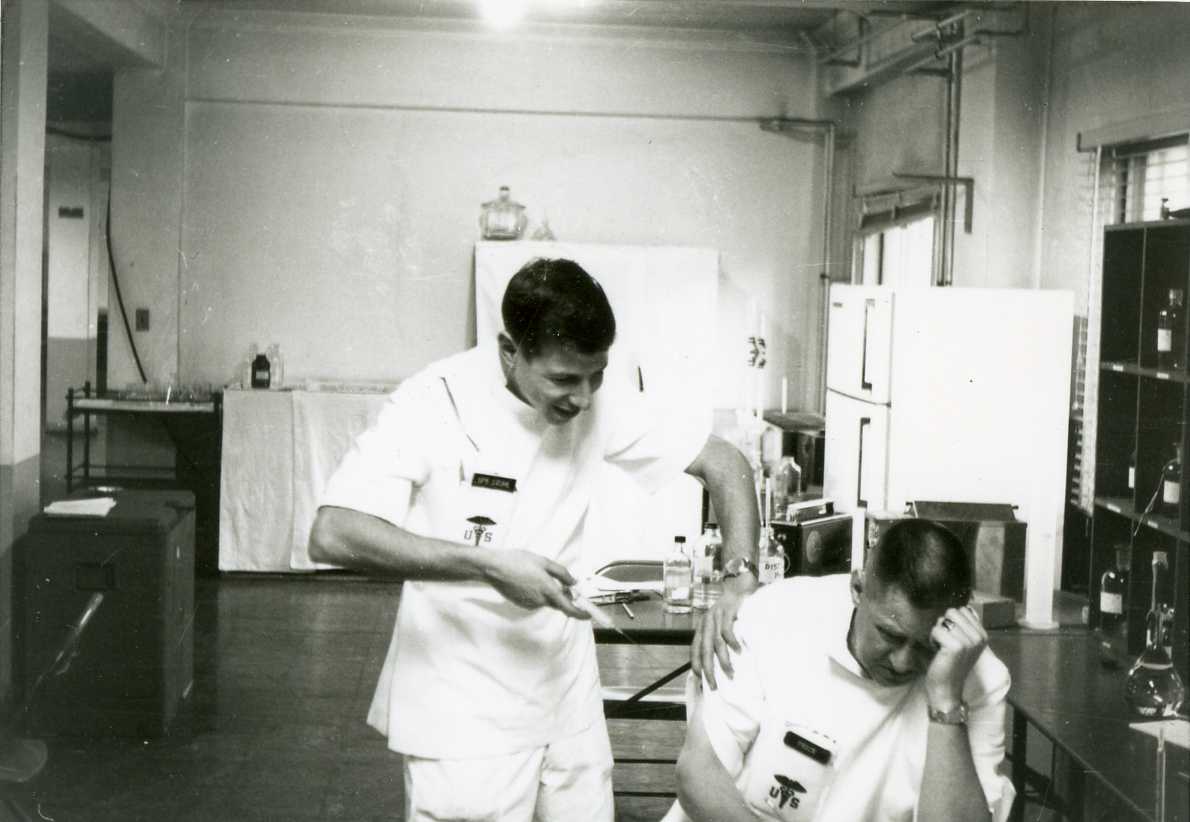

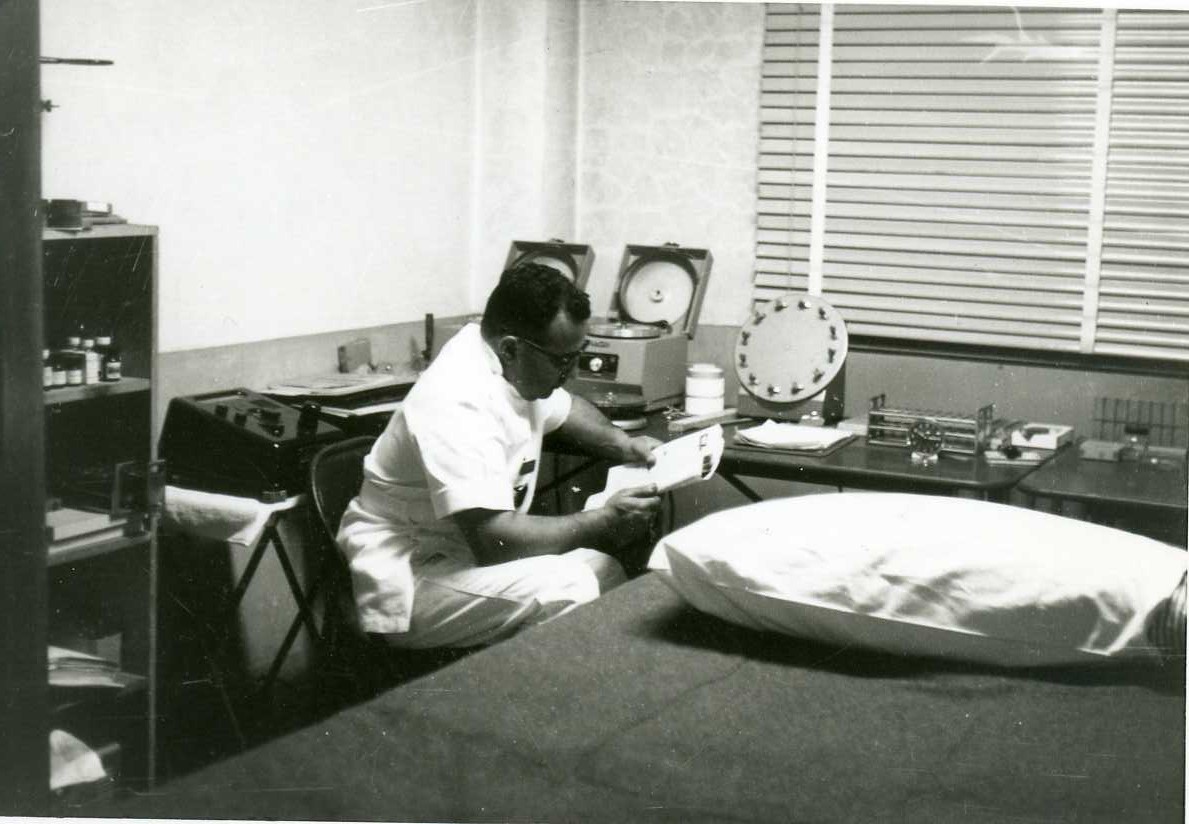

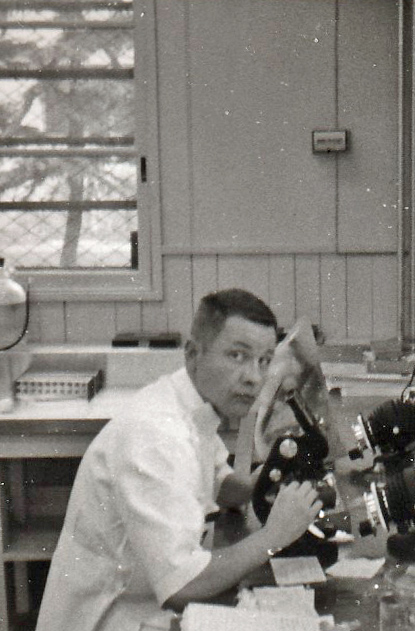

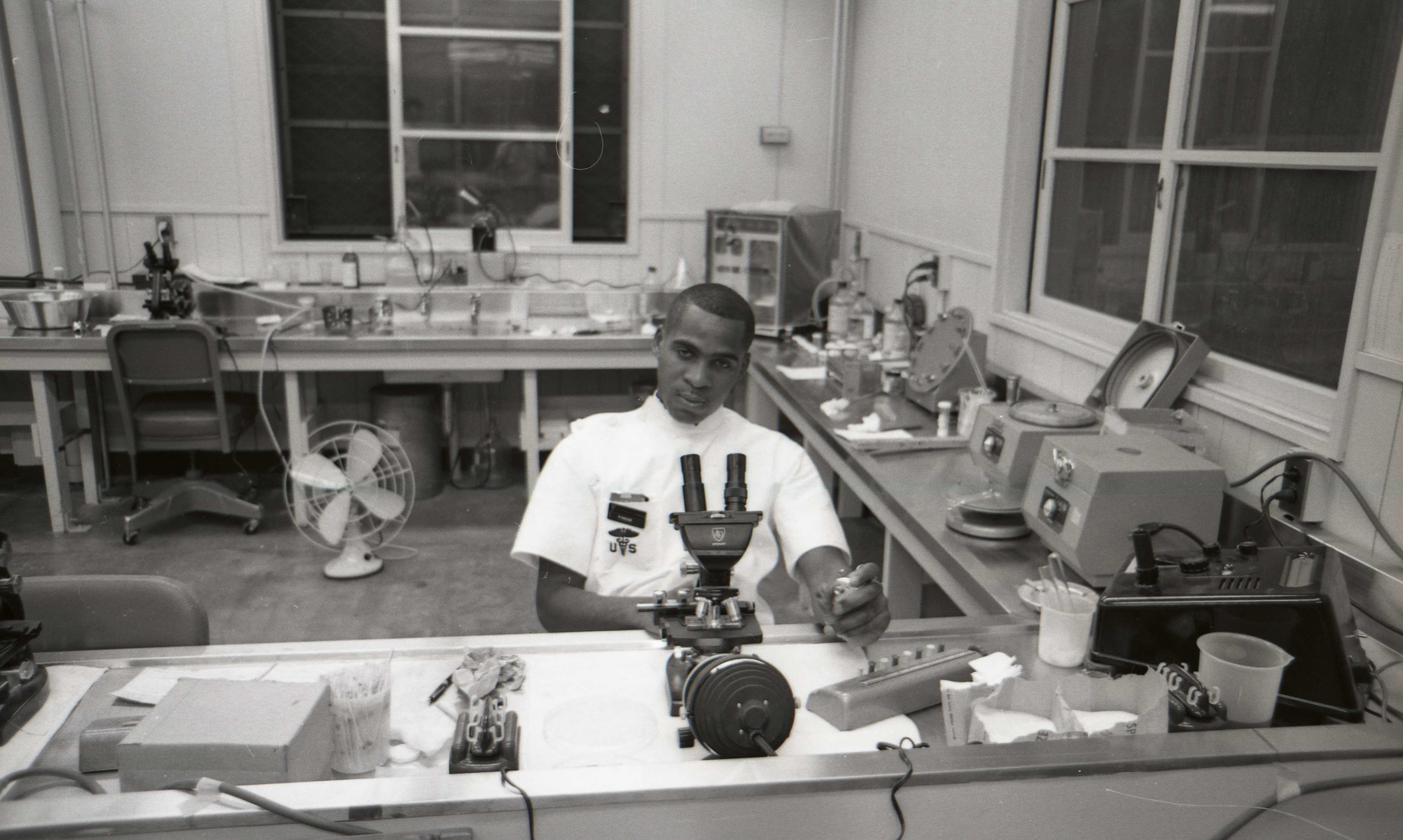

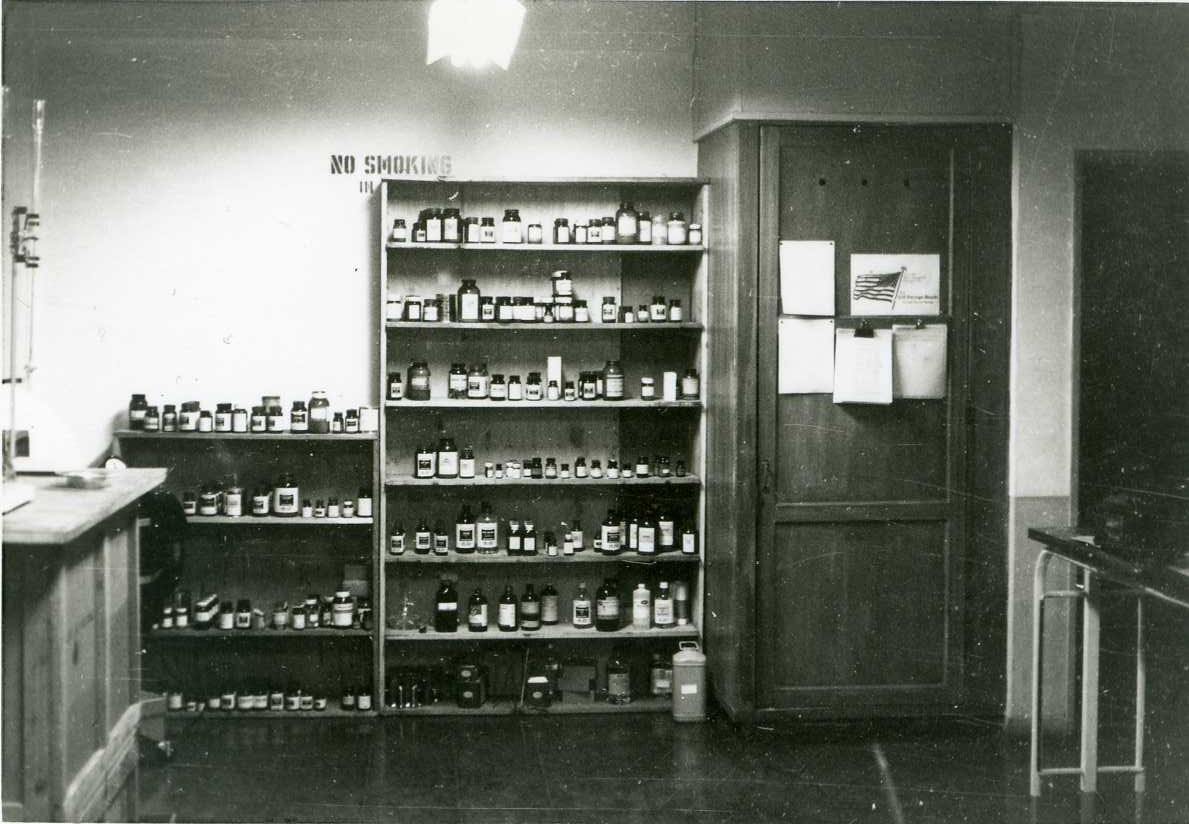

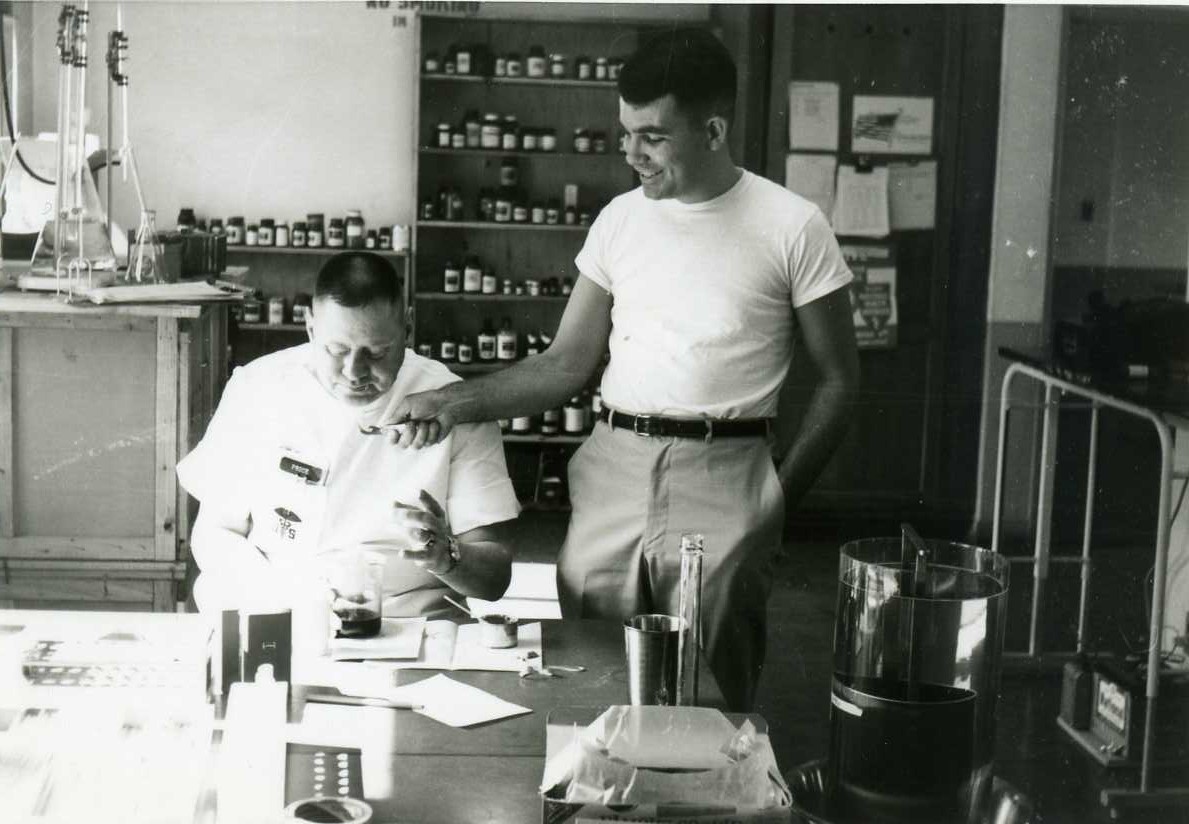

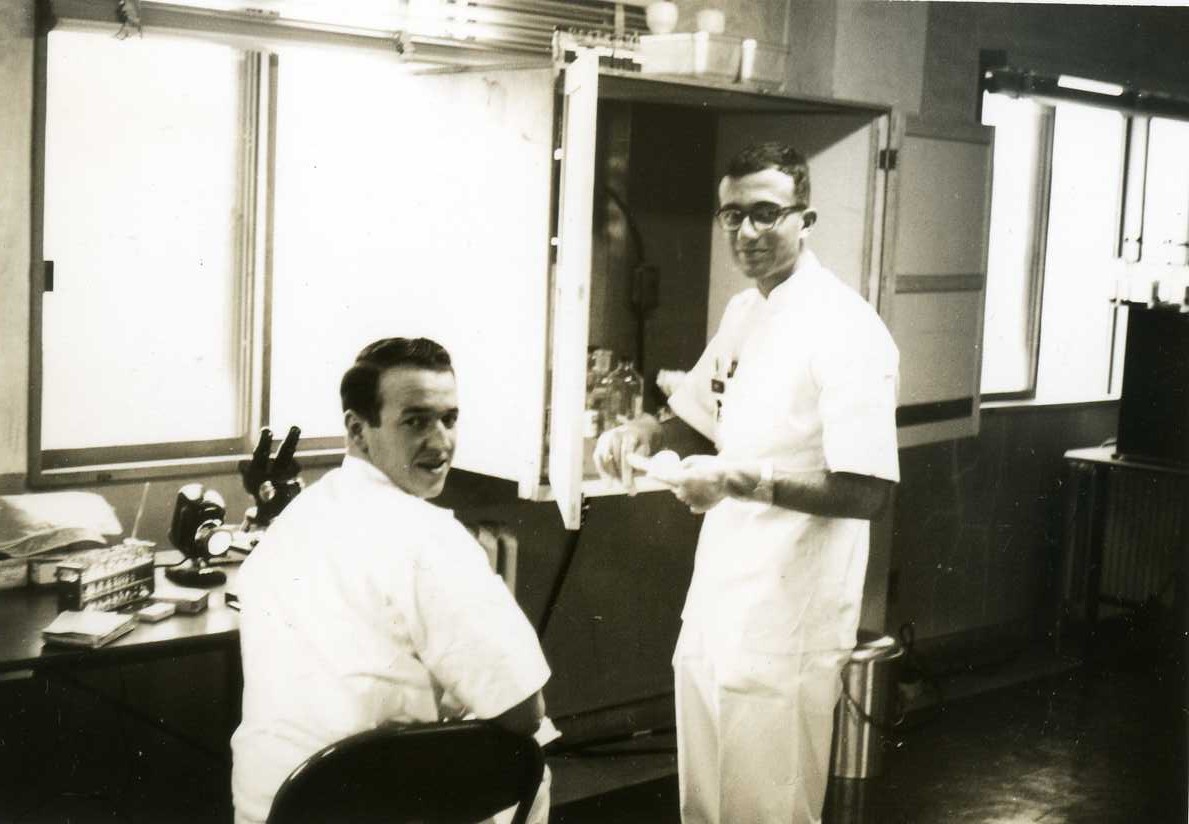

Clinical pathology

Hematology

•

Serology

•

Urinalysis

•

Blood chemistry

•

Bacteriology

•

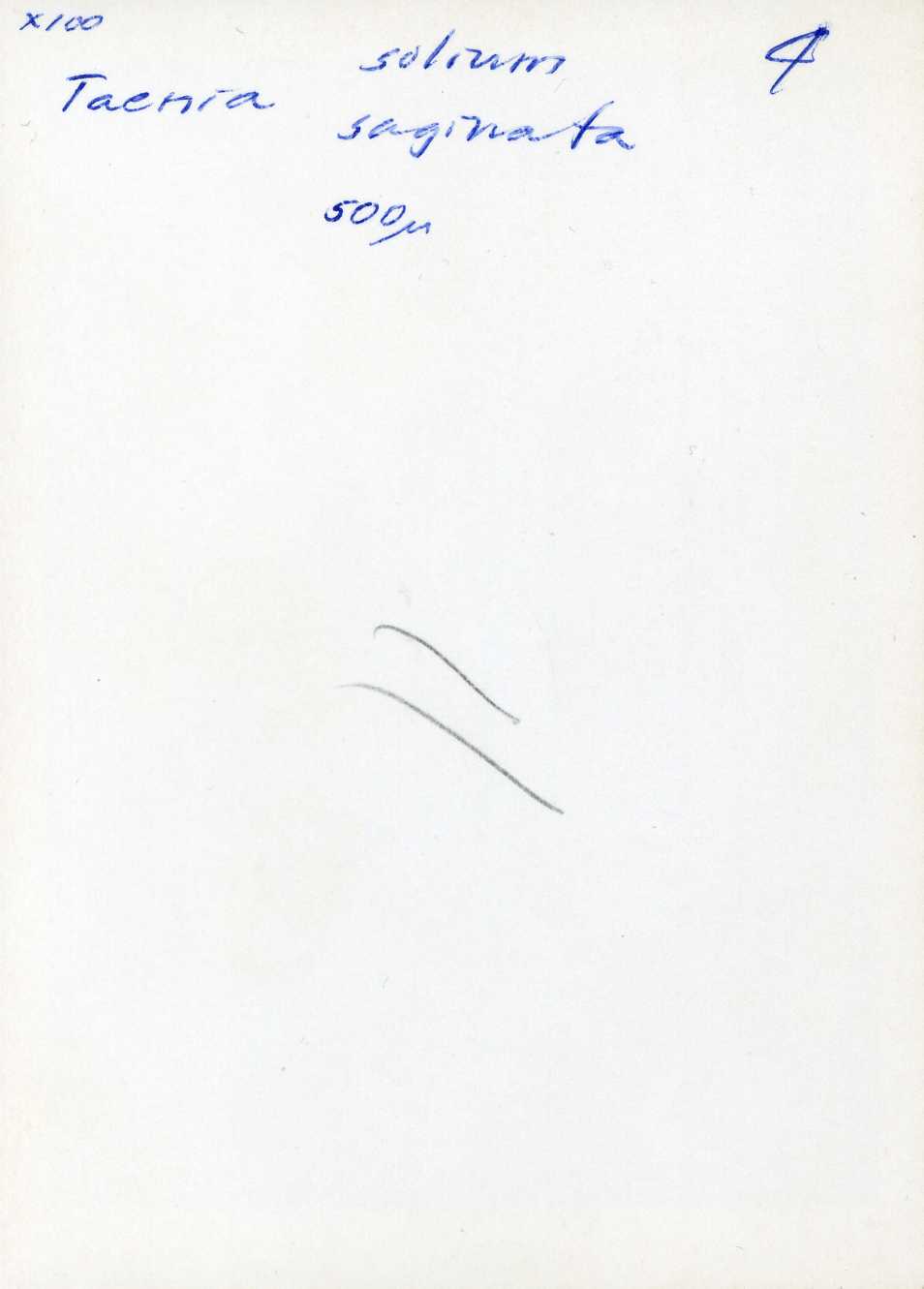

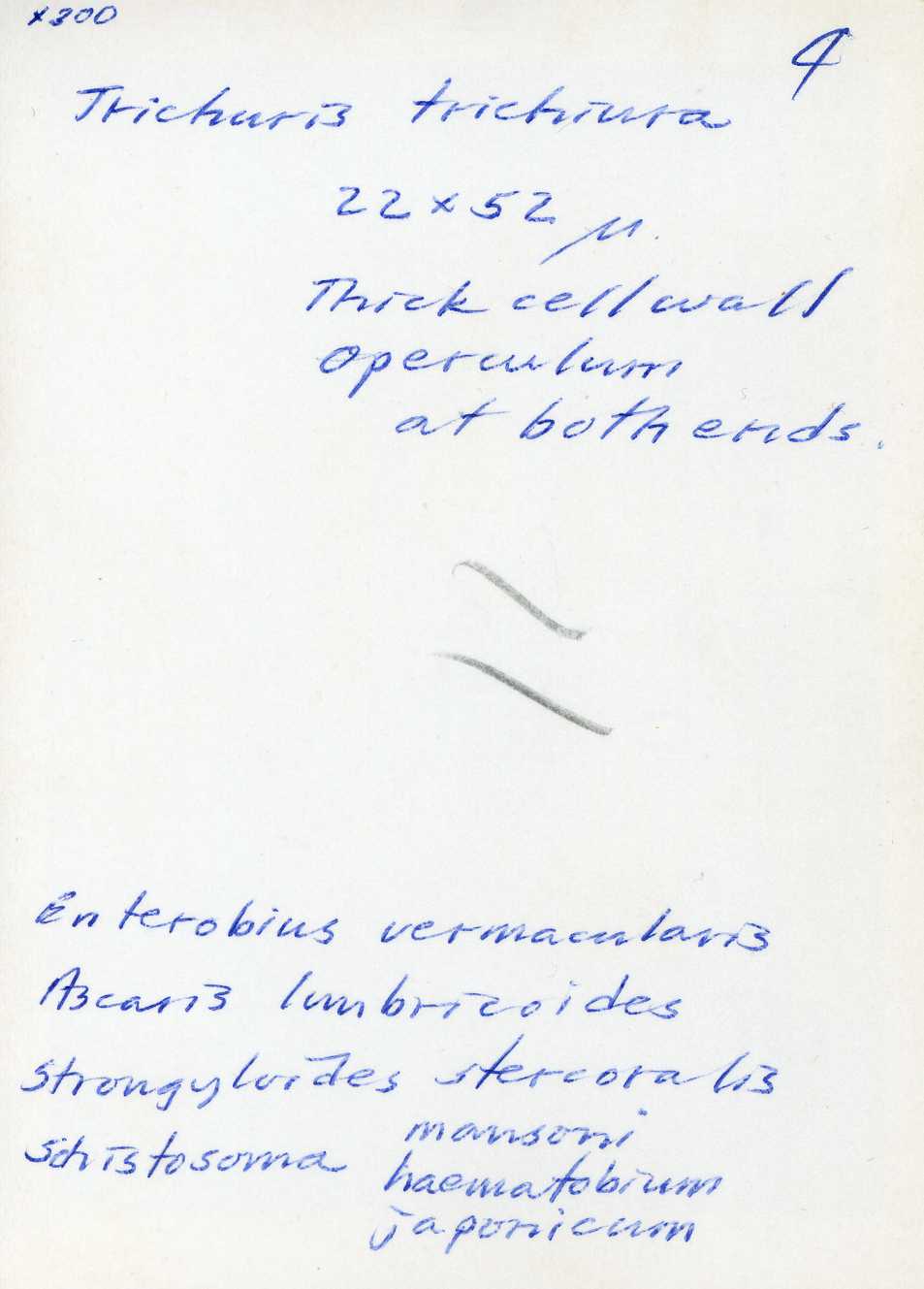

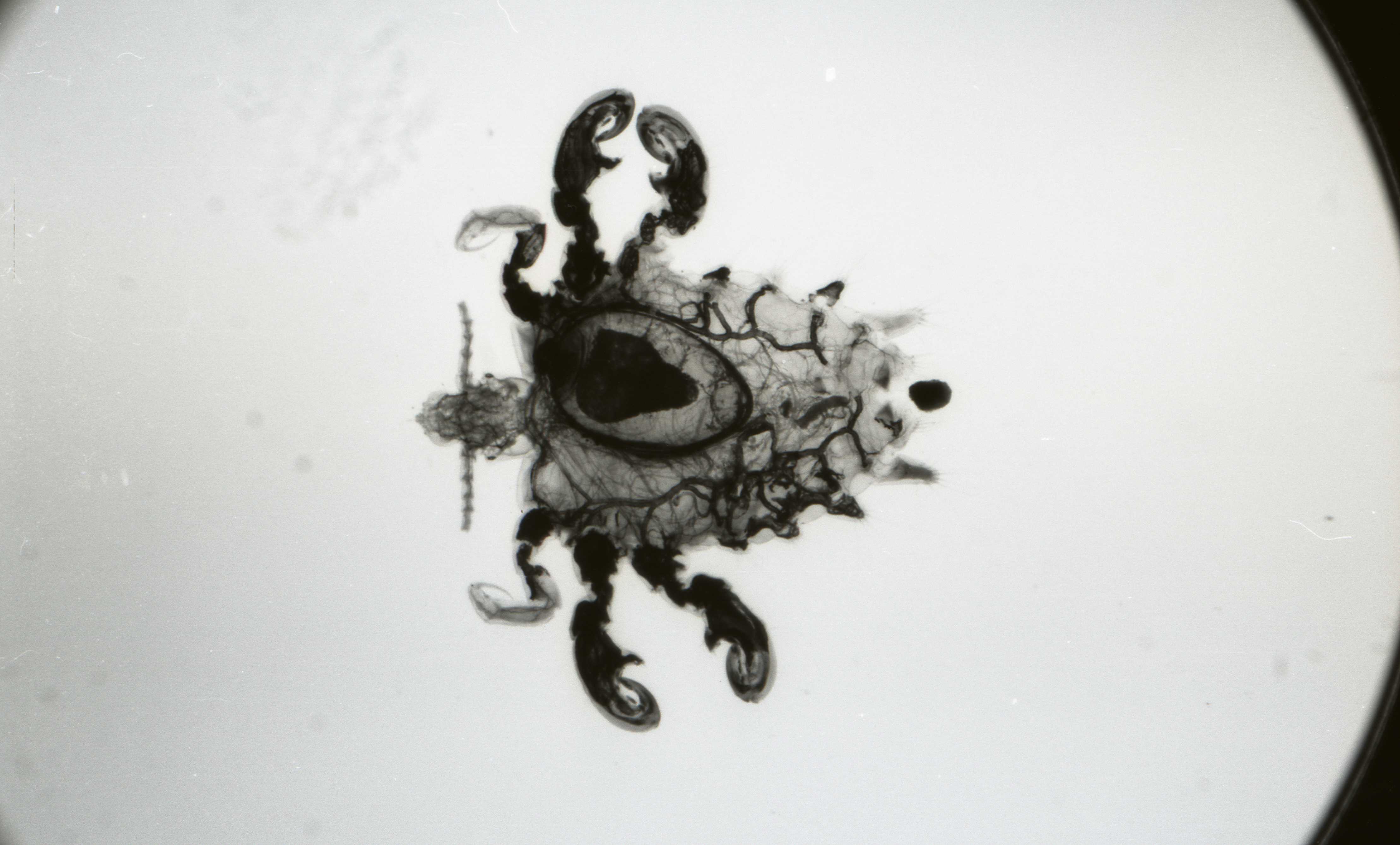

Parisitology

•

Histology

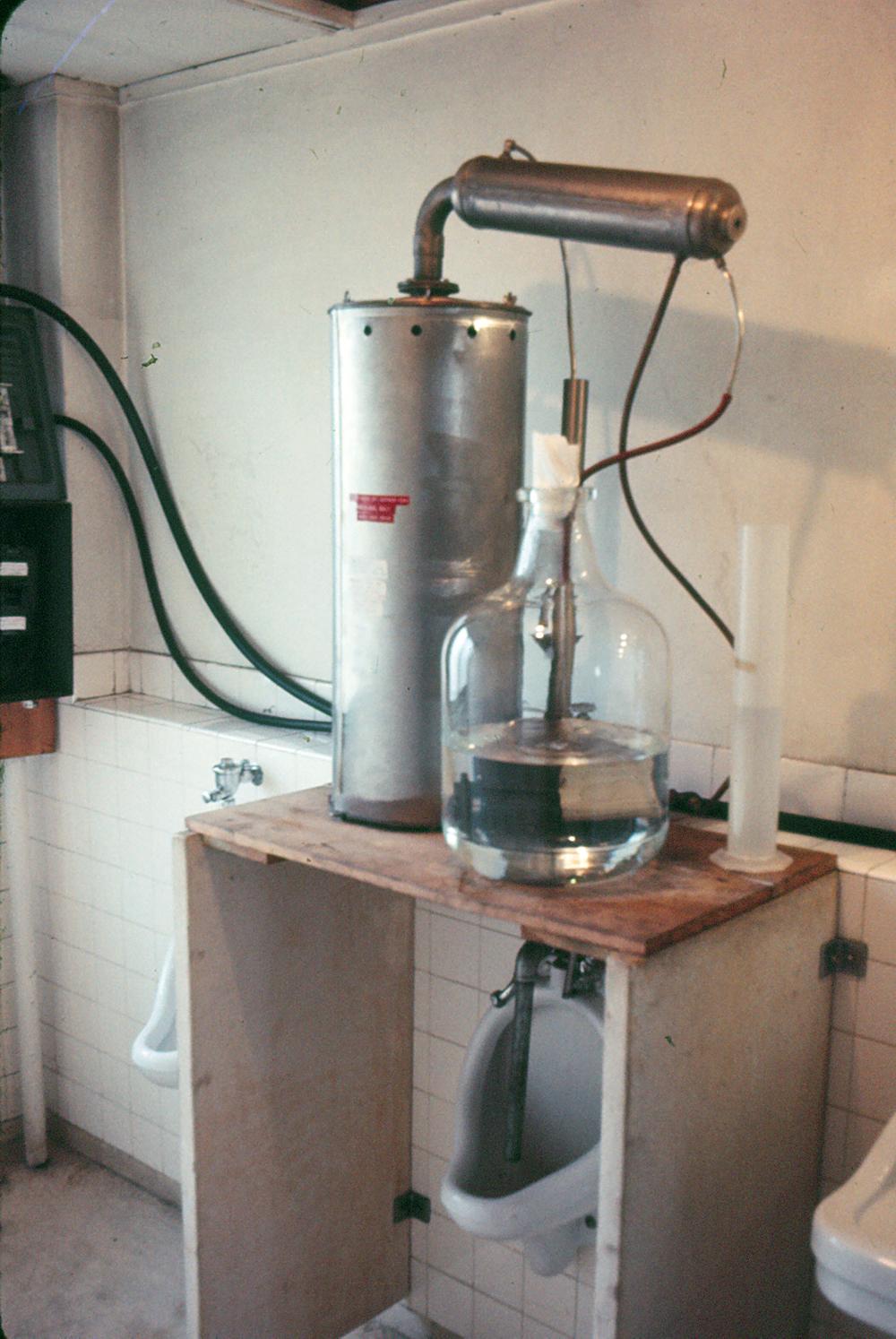

Making do

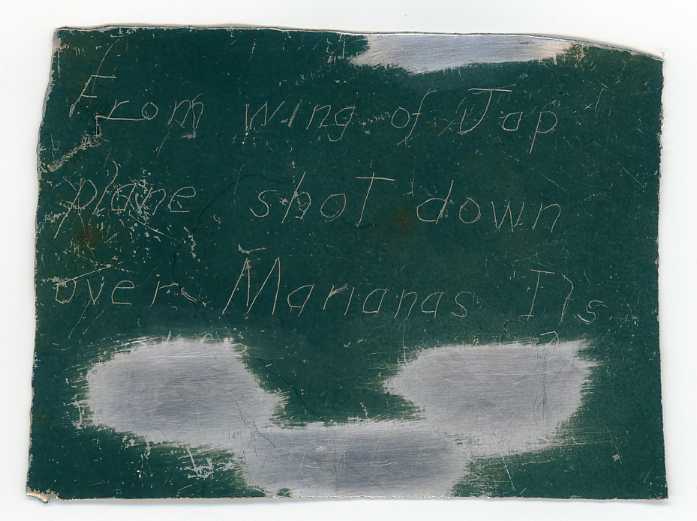

The small box from Japan

Looking back

Crossing the tees and dotting the eyes of a life half lived half a century ago

Kishine Barracks and the 106th General HospitalWar, protest, and urban legends in

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

File Unit: Combat Area Casualties Current File, 6/8/1956 - 1/21/1998 Brief Scope: This series contains records of U.S. military officers and soldiers who died as a result of either a hostile or nonhostile occurrence or who were missing in action or prisoners of war in the Southeast Asian combat area during the Vietnam War, including casualties that occurred in Cambodia, China, Laos, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and Thailand. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)Record Group 330 What information is in these records? Why were these records created? [ . . . ] Well, what was it? A "war" or a "conflict"? And whichever it was, was it a "Vietnam" or a "Vietnamese" event? In Vietnam, it is apt to be called the "Chiến tranh My quốc" ("America War" �č��푈) or the "Kháng chiến chống My" ("Resistance War Against America" �ΕčR��). "Conflict" doesn't quite capture the scope and the scale of the violence. And "civil war" -- never mind that this expression is an oxymoron -- doesn't account for the extent that the war was so Americanized. |

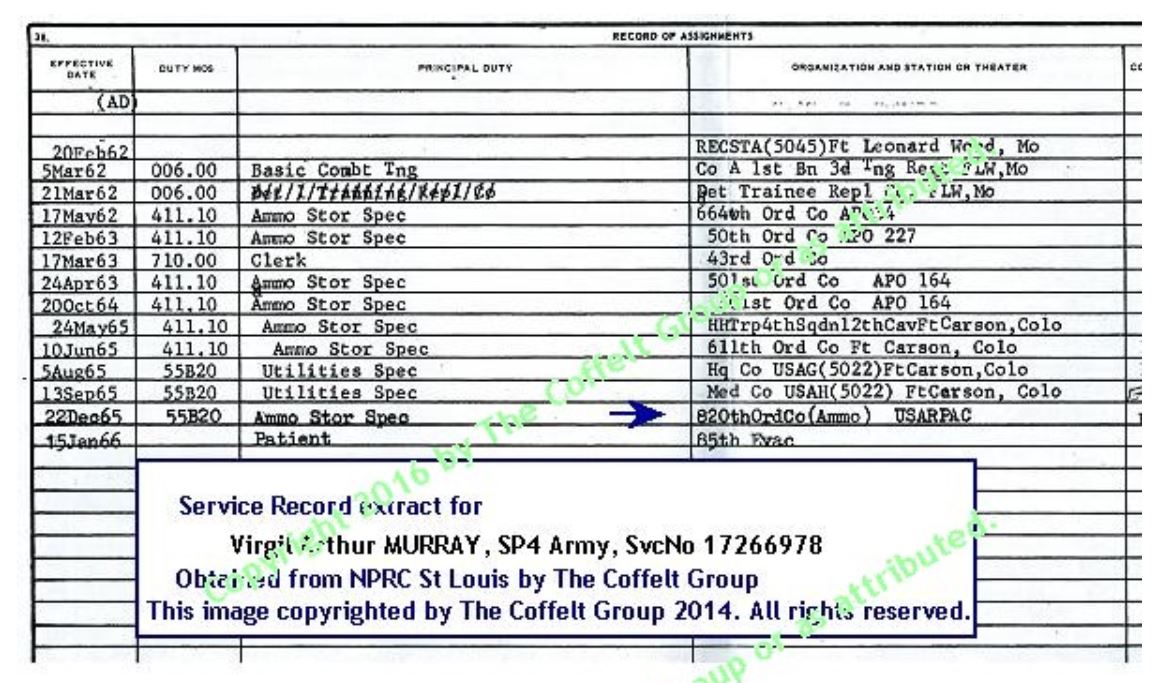

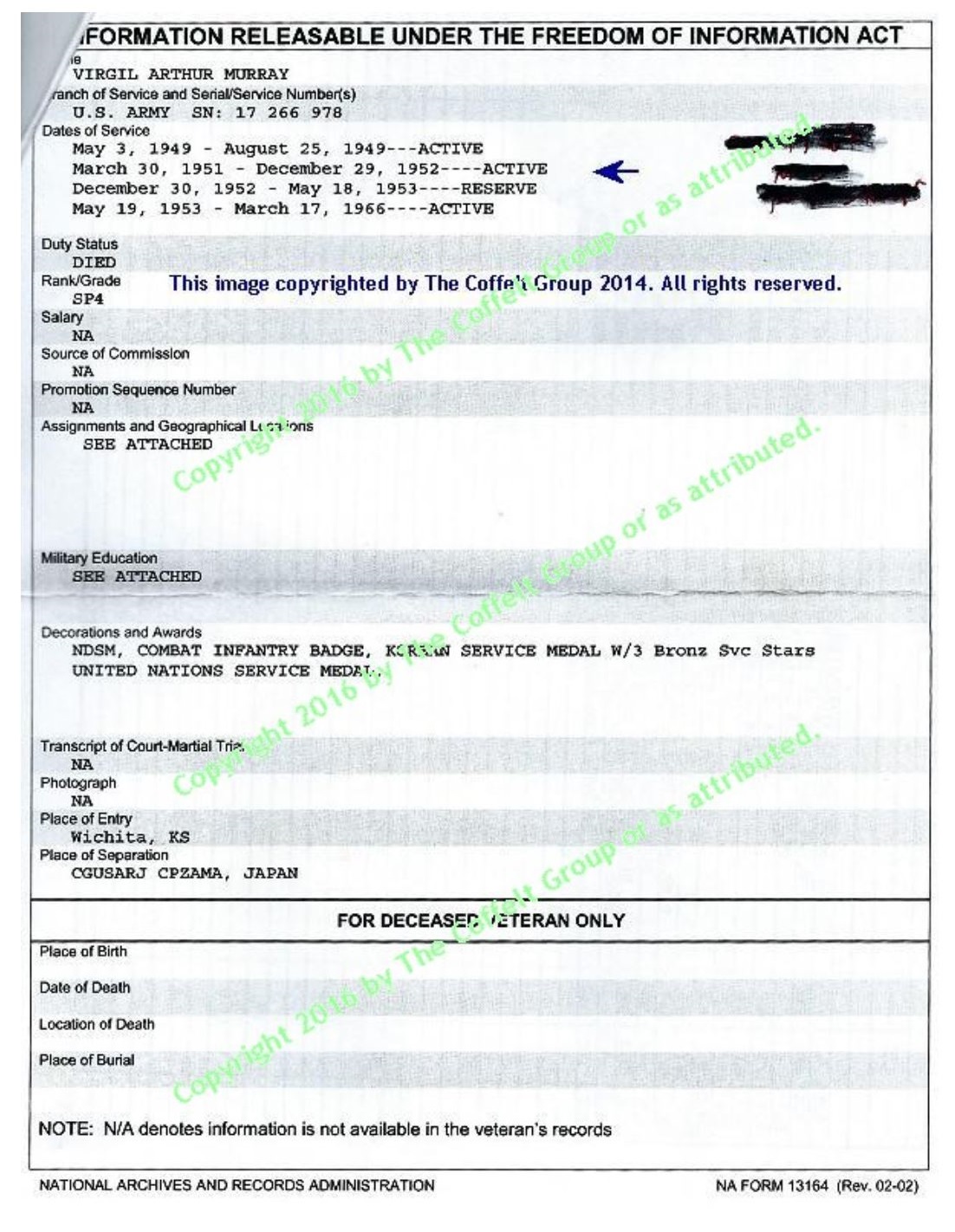

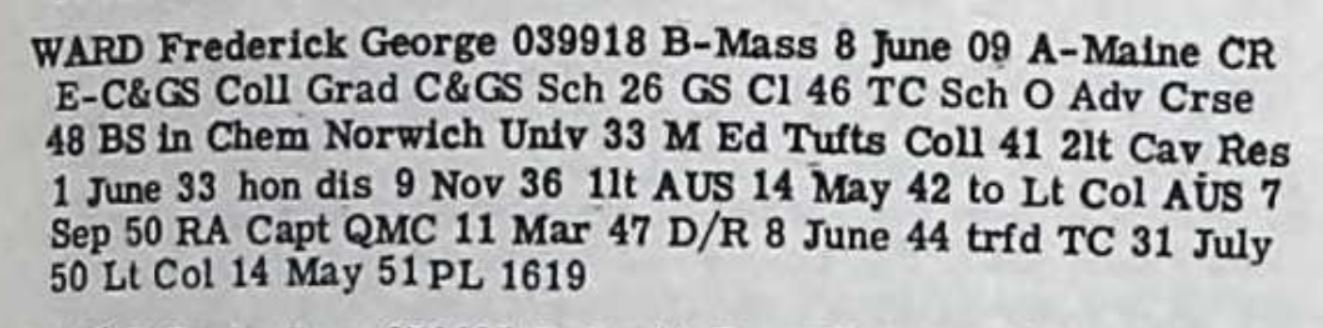

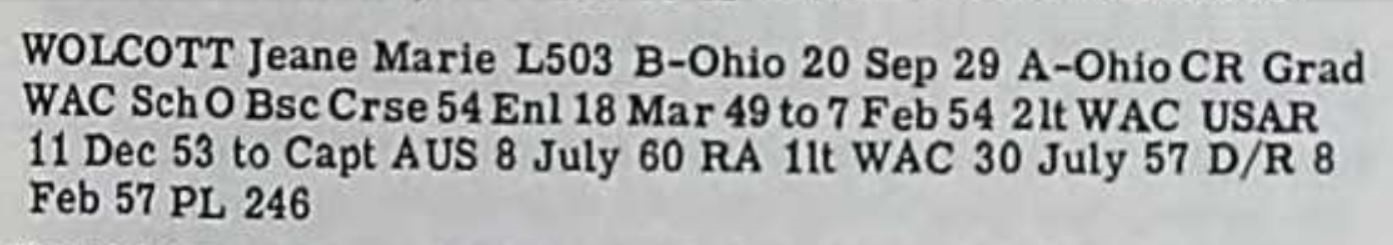

Coffelt Database

The Coffelt Database (CDB) of Vietnam casualities is the brain child, and the fruit of the labor of love, of Richard Coffelt and others. The CDB website describes him as "the first person to make a dedicated effort to identify the unit assignments of the Army's Vietnam dead, and did so with only the assistance of his wife Jo Ann Jennings until the late 1990s." From 1998, others, practically all veterans like himself, have joined him in compiling massive quantities of data on Vietnam veterans from various public records and other sources.

CDB and CACCF have many fields in common, but a few fields are unique to each. See Three soldiers in two casualty databases for a comparison of the kinds of information they contain. Two of the soldiers died at the 106th General Hospital. The third was a brother of a doctor at the 106th, who according to one account had visited the 106th on an R&R.

The strongest feature of the CDB website is the links it has to scans of primary records for not a few of the "casualties" in the database.

The Coffelt Database is also accessible through the above NARA AAD portal. The manner in which the returned data is presented, however, is somewhat different.

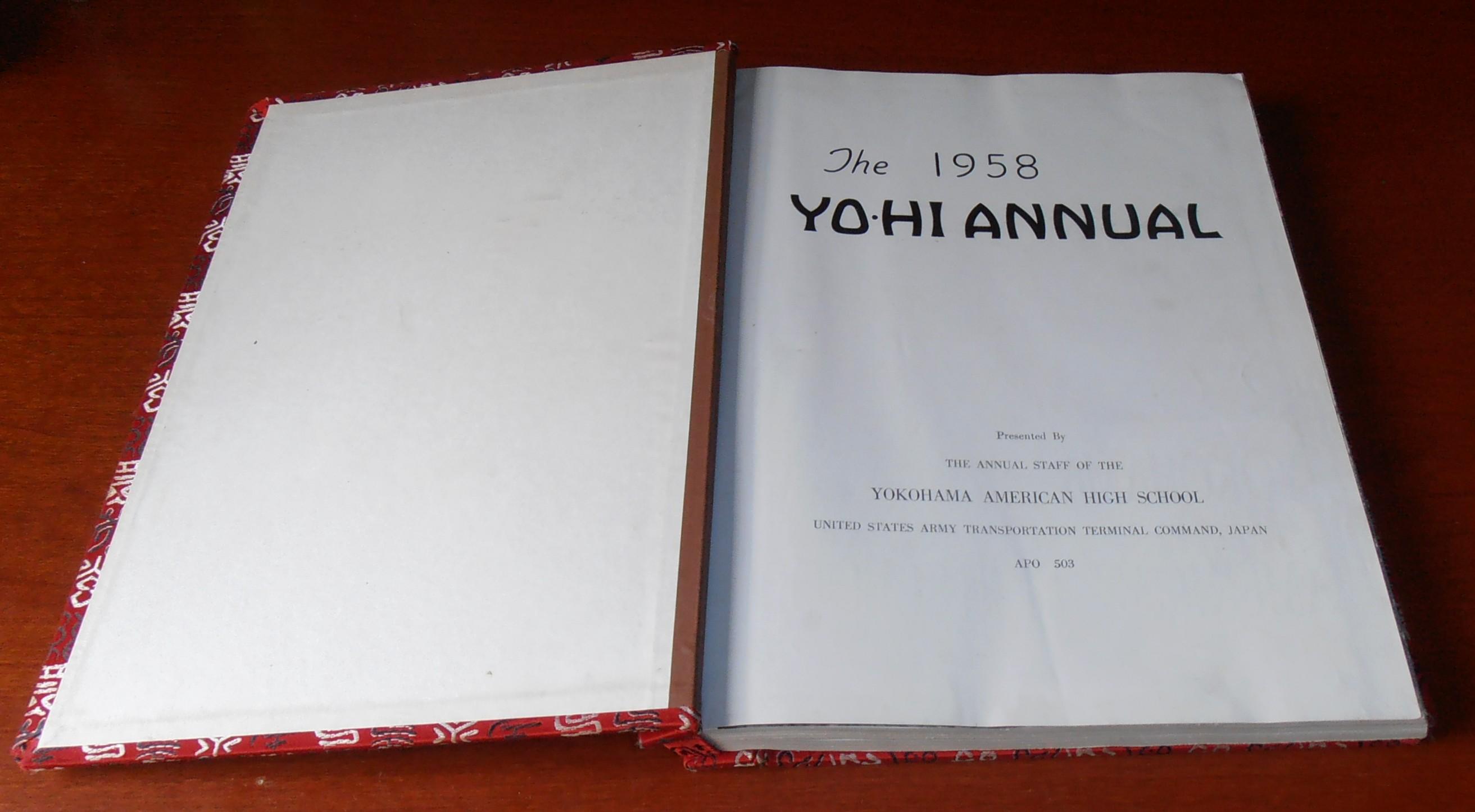

Genealogy databases

In research on historical figures, and on my own family history, I have made extensive use of Ancestry.com, a commercial subscription-based genealogy resource. Ancestry's databases include scans or transcriptions of all manner of public records, from national censuses and birth, death, marriage, and divorce records, to draft registration cards, passenger manifests, naturalization records, and other civil records, as well as newspapers, city directories, high school and college albums, and other publications that allow one to compile an enormous amount of information about some -- but not all -- individuals and families.

The amount and quality of the information available through Ancestry.com will heavily depend on when and where a person lived, as states considerably vary in their laws and policies regarding making public files available on the Internet. Moreover, the availability of information compiled by U.S. government also varies with period.

None of the information available through services like Ancestry.com is privileged. All of it is available to anyone who walks into the office of the competent state or federal agency, or the controlling county or municipal registrar, or a cemetery.

The development of computers, database software, and electronic image scanning -- and of course the Internet, which mediates access to an increasing percentage of all available information -- makes it possible for to collect and collate, in just one day, information that would have take months of expensive travel and labor-intensive thumb searching and manual transcribing of the kind I remember doing when a college student before the age of personal computers and the Internet.

Even through portals like Ancestry.com, however, information does not fall from virtual trees. You have to learn how to query their databases to find what might -- possibly -- be related to whoever you are looking for. It's easy to spend an hour or two and come up with nothing.

You need at least a family name, and a birth or death date, just to begin to get nothing. Even if your spelling is a bit off, or a date is wrong by a year or two, you might stumble across the person you're looking for. Perfect matches are nice, but you have to rule out the possibility that it might be someone else with the same or similar specs -- hopefully with independent information, even if only a fragment from your or someone's memory.

Memory

Memory is always a problem when talking about the past, even if only 5 hours ago, to say nothing of 5 decades. Some things I remember with great confidence because I have never not remembered them. Other things have faded in and out of my memory, though not always in the same manner. And many things I have entirely forgotten.

There are moments when I feel I have recalled names or experiences I thought I had forgotten. At times they appear without stimulation from related thoughts. Other times they float into my mind only after I have had related thoughts. The dilemma of memory is that you can neither ignore such recollections nor take their veracity for granted.

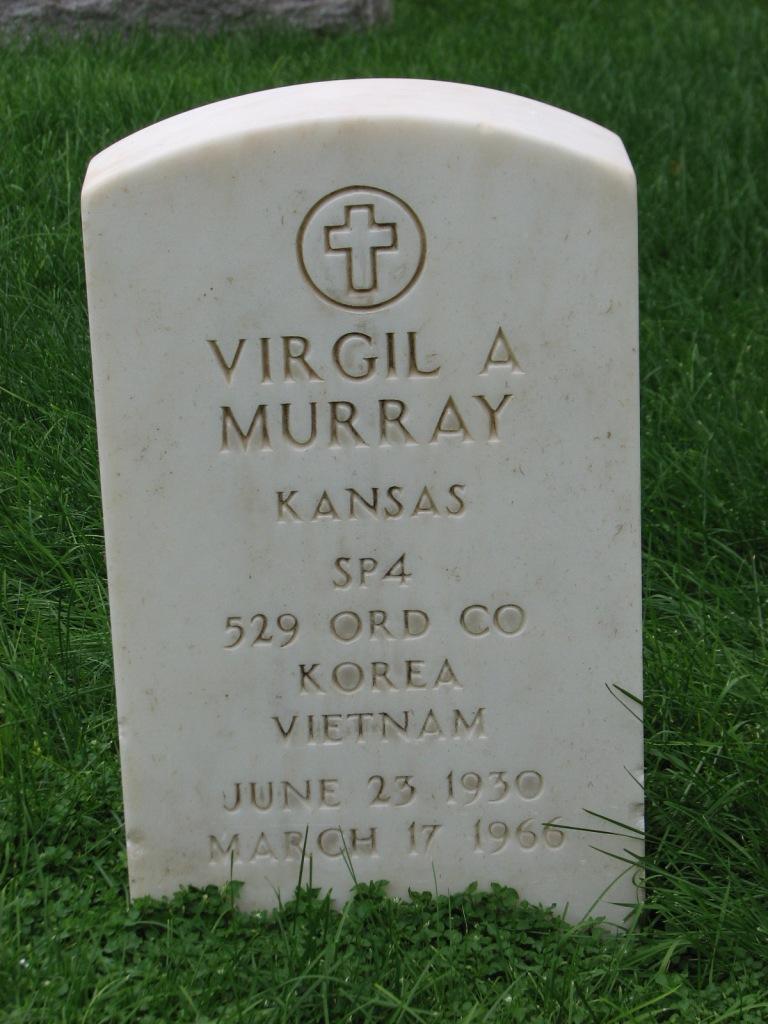

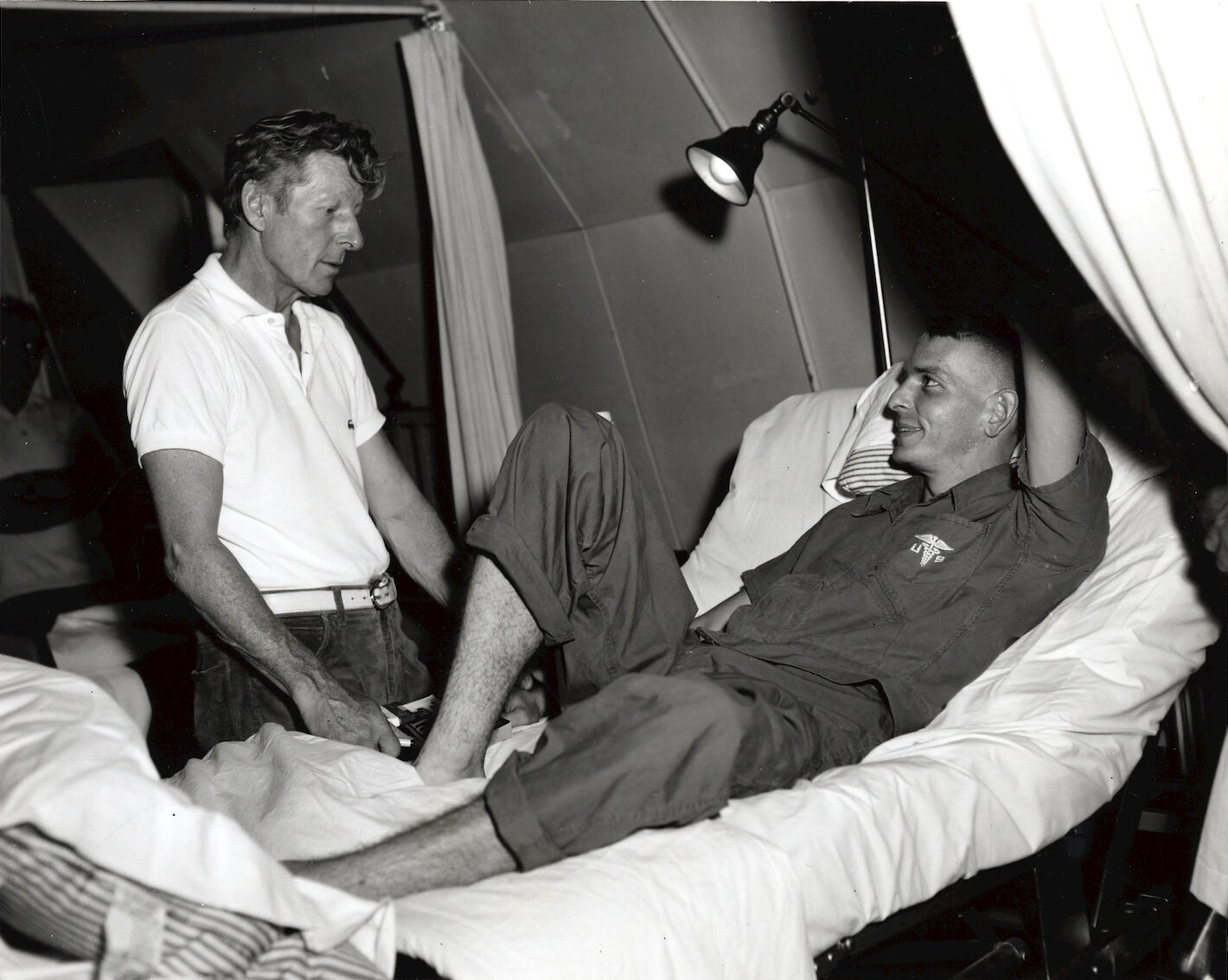

Murray

I clearly remember "Murray" as the name of the first patient who died at the 106th General Hospital. How could I forget his name? He died on my watch so to speak, in the spring of 1966. I had drawn his blood, including -- shortly before he died -- at least one blood culture.

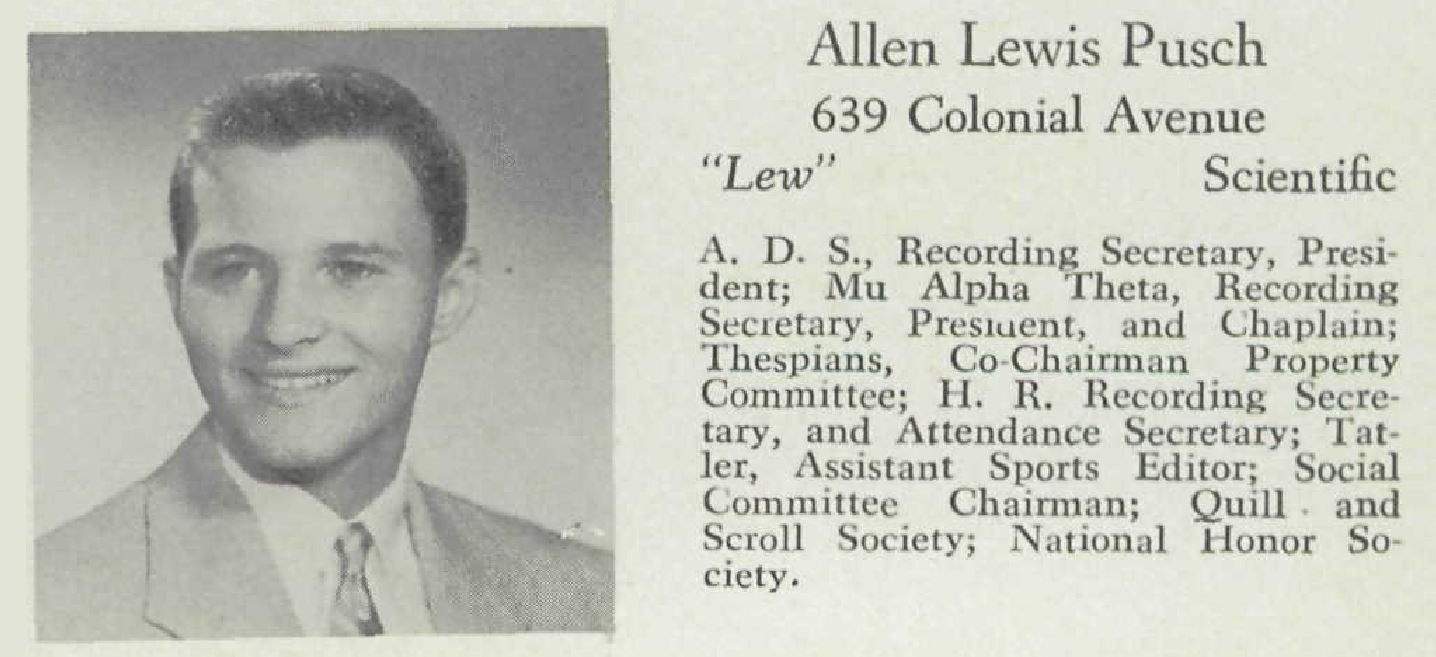

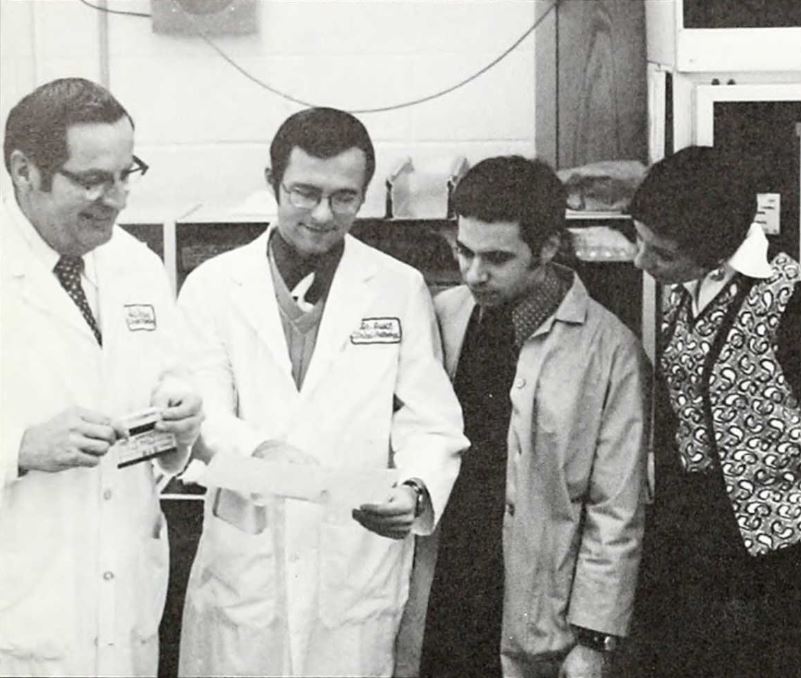

The name "Murray" is deeply etched into my memory, also because he was autopsied at another hospital by -- or with the assistance of -- Dr. Pusch, who was the head of the pathology laboratory where I worked. Dr. Pusch brought Murray's brain back to the lab and dissected it in an impromptu anatomy lesson.

I worked mainly in bacteriology but was a histopathology junkie. I obtained a set of Murray's tissue slides, which were among other slides I had collected while working at the lab and took with me when I left. The slides were in my possession until very recently. "Murray" was clearly written on the labels of autopsy slides, which had "106th Gen Hosp" printed on them.

Yet, by the time I got around to writing this history, I couldn't remember Murray's personal name or other things I had once known about him. Was it Geoffrey or Jeffry? Or another name enirely? I was fairly sure, but couldn't have sworn, that he wasn't a draftee. He wasn't old but he was older and had been in the Army awhile.

But I knew with certainly the year and place Murray died. And this, eventually, allowed me to find the Murray I had known, in the vast sea of Murrays who have died while in the miltary.

In many other respects, though, my reconstruction of Murray's difficulties at the 106th General Hospital continues to be plagued by a number of fascinating memory dilemmas, which are evident in my closer look at Virgil Murray (1966) (below).

Fact checking

The most tedious challenge when writing a history like this is "fact checking" or so it is called. This entails determining the factuality of everything you write -- not only of things based on your own or someone else's memory, but of information found in putatively reliable sources, from birth certificates to the most authoritative dictionaries.

The keyword in fact checking is skepticism. No matter how reputed the source of some information, the factuality of the information should never be taken for granted. A lot of information that passes for "fact" turns out, when closely scrutinized, to be someone's "impression" or "opinion" or "bad memory" if not "imagination".

Not only are memories tricky, but official records, and official and academic histories and other reports, can be full of misinformation. Misspellings, wrong dates, faulty descriptions, untrue allegations, and misleading or biased commentary are all "natural fauna" in the jungle of bureacratic, historigraphic, and biographical writing.

In writing this history, I have spent a lot of time trying to confirm the accuracy of the names, dates, and other matters I have written about. My resources, though, are limited, partly by the fact that I am unable to spend years doing the sort of footwork required to examine original records and personally interrogate the people I have written about or their survivors.

As it is, this history relies more on Internet sources than anything else I have written of comparable length and scope. In fact, even ten years ago it would have been impossible to write and illustrate this report as I have. In just the past decade, the Internet has exponentially swelled with data in the form of blogs and vanity sites created by veterans and unit organizations, and government records and newspapers are being scanned and uploaded to servers at accelerating rates.

Fact checking is reaching the point that, if you can't confirm the factuality of something on-line, a relatively efficient process in terms of time consumption and material outlay, you face the diminishing returns of physically exploring actual libraries, archives, and records the "old fashioned" way, with prospects of spending huge amounts of time and money to discover little of earth-shaking value.

The quality of the most carefully confirmed facts, however, can be corrupted by poor editing (next).

Editing

All texts in yellow boxes are Citations and texts in green boxes are Comments. All boxed comments, and [bracketed remarks] in cited texts, are mine. Unbracketed ellipses . . . are as received, but bracketed ellipses [ . . . ] are mine.

I have not corrected or otherwise altered the text of any citations. When necessary (and perhaps also in some cases when not really necessary), I have [brackted corrections] in the form "incorrect [sic = correct]". In some cases I have shown just [sic] to stress that the word or phrase it follows is as received and not a transcription or scanning error.

Transcripted and scanned texts

Some citations are my transcriptions of printed texts or images of such. I have endeavored to check that my transcriptions are accurate but there is always the possibility that I overlooked an error of my own making. Numbers are especially problematic.

I have also checked all citations of texts I generated with on-line OCR (optical character reader) image scanning services. When scanning pages of printed text to create electronic text, you have to check the results for scanning errors, no matter how clear the original text.

Certain letters and numbers, and combinations thereof, can be corrupted by even the better optical character reader (OCR) software.

The combination "rm", for example, often comes out "m", and sometimes with amusing consequences. Many instances of "burn" and "burns" came out "bum" and "bums" -- which spelling checkers can't detect, and even the naked eye can miss unless you read very carefully.

The number "1" and lower case "l" and upper case "I" are commonly corrupted. Numbers "3" and "5" and "8" are easily confused and need to be checked when transcribing or scanning texts. "6" and "9" are also subject to visual confusion.

I habitually compute sums and percents of all received statistics in order to confirm that I have transcribed or scanned them accurately. In the process, I sometimes find errors in the received data.

Frankly, I have less confidence in screen editing than in the sort of hard-copy editing I grew up and even old with. Today, when reading printed or electronic publications, I spot more errors than in the past -- errors that have the characteristics of what I call "word processing errors" -- by which I mean errors created by people using word processors to write and then check their writing on a monitor. Occasionally I find such errors in my own writing -- traces of phrases I intended to delete, undetected auto-correction errors, inadvertent spelling checker errors.

Spelling checkers have to be used with care. Grammar checkers are to be turned off. Writing rules are meant to be broken, though with discretion, and always with the ear, not the eye.

In the vetting process, my eyes cross and invariably I miss things. I trust everyone will forgive me, and laugh just as I did, when I first encountered expressions like "bum center" and "bum patients" and "3rd-degree bums" in scanned texts.

Corrections

I have taken the liberty of weaving the stories of many people into what is ultimately my own story. I have cited numerous public sources, but have also used personal materials, including photographs taken with my camera and letters received from correspondents, without consulting with the people they involve, some with whom I am no longer in touch, others who have passed away.

I have also depended heavily on my memory, which is not always clear, and even when clear cannot always be confirmed by independent objective evidence. No memoir of this scope is free of error, and errors will run the gamut from slight variations in spellings and dates, to confusions of names and places, and otherwise incorrect descriptions and allegations -- on my part, or on the the part of others whose errors I overlooked or was unable to detect.

I welcome all comments, suggestions, and corrections, and will honor requests for deletions of personal information, or of citations or use of any material, that related parties find unacceptable.

Please send your remarks or requests to me through the Contact form and I will reply as soon as I can.

Abbreviations of medical, military, and other terminology

Some reports and records cited in this story of Kishine Barracks contain from several to many military terms and their abbreviations. Some are common to military organizations and operations generally. Some are limited to a particular military branch such as the U.S. Army, or to a specific field su. Some are common also to military organizations in other countries where English is officially used. Many, though, are specific to a particular service, and a few are specific to a particular period or war.

I have listed here, for reference purposes, abbreviations that appear in this story of Kishine Barracks and some related terms of interest.

Abbreviations of medical, military, and other terminology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Japanese temrs

This history of Kishine Barracks and the 106th General Hospital is lightly sprinkled with Japanese words and expressions, but some Vietnamese terms, and a few Korean and Chinese terms, also appear. Here I will focus on Japanese, but at the end I will also comment on Vietnamese, Korean, and Chinese in relation to Japanese (though linguistically only Japanese and Korean are possibly related).

Japanese sources

I have cited a number of sources that are written in Japanese. All English translations from such sources are mine.

Japanese sources are likely to be faulty for the same reasons that English sources are faulty -- unconfirmed memory or hearsay, failure to check facts, unintended ambiguity, impulses to censure or slant or embellish, and over generalize. Hence I take everything I hear and read in Japanese, beginning with street directions from local residents, with the same sense of caution that I take everything I hear and read in English.

Blind faith in the accuracy of what you are told or taught or learn may get you lost. Researching this history of Kishine and the 106th has been an adventure in finding myself somewhere I didn't expect to be. At times I worried if I'd ever get to where I hoped to be, only to discover that where I hoped to be didn't exist. There were few signs. And for every sign pointing down the right road, there was one pointing down the wrong road, and one pointing into the wilderness.

Japanese words and expressions

When citing a Japanese word or expression, I have generally shown how it would be written in Japanese script and/or Chinese (Sinific, Sino-Japanese) graphs, as well as how it would usually be romanized (alphabetized). I have also of course shown its approximate meaning in English. I have glossed some of the more important words or expressions in greater detail.

Japanese as a language

Japanese is the native language of practically everyone who lives in Japan. My life in Japan, and my life of writing as a journalist and researcher, would have been impossible without learning Japanese.

A lot of people in other countries have gotten the impression that Japanese is a difficult language. But as my first college teacher of Japanese put it on the first day of class, all people in Japan speak Japanese, and half of them are stupid, so it couldn't be that difficult. Well, yes and no. But his point was well made. Linguistically it is not at all difficult. Graphically, most people who are learning Japanese as a foreign or second language have work at the writing and reading. But even that is not as difficult as it may seem at first glance.

"Kishine"

Everyone at the 106th, who stepped outside Kishine's gate, quickly realized that they had crossed a linguistic divide. Phrasebooks were common, but they didn't get one very far.

"Kishine" in some ways represents the language -- which, I would point out, is what is spoken and heard, not what is written or read. Scripts -- alphabetic and other symbols -- respresent sounds, but they don't pronounce themselves.

Linguistically, "Kishine" consists of 3 morae -- "ki-shi-ne" -- pronounced roughly "key-she-neh" if representing the sounds in aphabetic script most speakers of English will probably pronounce the way most speakers of Japanese will probably pronounce Japanese moraeic script (kana) -- ������ (hiragana) or �L�V�l (katakana) -- or �ݍ� (kanji), as the word or name would be written in Chinese script.

In English-based aphabetic representations (romanizations), the name is written "Kishine" (Hepburn system) or "Kisine" (Kunrei system). In Japan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs generally uses the Hepburn system, while the Ministry of Education generally uses the Kunrei system. However, the Hepburn system is more popular internationally and more familiar in academic and journalistic writing.

The Japanese placename �ݍ� -- read ������ or "ki-s(h)i-ne" -- is written 키시네 -- not 기시네 -- in Korean hangŭl. The former would be alphabatized as either "K'isine" (academic or phonemic McCune-Reischauer) or "K'ishine" (popular or phonetic McCune-Reischauer) -- or as "Kishine" (Revised Romanization of Korean, ROK Ministry of Culture standard) -- or as "Khisiney" (Yale). The latter would be romanized "Kis(h)ine" (McCune-Reishauer), Gisine (ROK), or Kisiney (Yale). But who would want to do this?

The IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) representations used by some linguists, Kishine would be written "ki-ɕi-ne". The approximate English values are as follows.

k k as in skate i ee as in meet ------------------ ɕ sh as in sheep i ee as in meet ------------------ n n as in not e e as in met

However, some people who passed through Kishine Barracks or the 106th General Hospital have spelled Kishine in various ways -- including Kishini, Kishina, Kashine, Kashina, and even Kashini -- apparently in accordance with how they remembered hearing the word. It's a chicken-egg question.

There is only one Google return for "Kisine Barracks", on the Facebook page of a "Bud Schofield", who states under "Life Events" that he "Moved to Yokohama, Japan / January 10, 1960 / Kisine Barracks USMC". On the surface, he would appear to have been in the U.S. Marine Corps, which contributes to the developing image of Kishine Barracks as a multi-service Army facility.

So when doing on-line research for on the history of "Kishine", I Googled all of the above "variations" just to be sure I wasn't missing anything. Most likely, though, somewhere out there in cyberspace, there's a truly odd spelling that slipped through my imagination.

Some people have remembered "Camp Kishini Barracks Hospital" as being at "Yokuska Naval". Yokohama, Yokota, and Camp Zama sometimes come out Yokahama, Yakota, and Camp Zuma, among other spellings. A few have placed Kishine in Tokyo, and one writer has located "Kashini Barracks" in Korea.

The linguistic origins of spelling corruptions

"Yokoska" is an unconventional spelling but it reflects a good ear. As spelling corruptions, "Kishini", "Yokahama", "Yakota", and "Zuma" and the like reflect bad ears or bad memories.

Native speakers master the sounds of a language before they learn how to represent it in script. One can grow up and die of old age, never having learned to read, much less write, and be a totally competent speaker of the language. As I say, writing is not language.

Non-native speakers who flirt with a language whose sounds they have not mastered through the ear, to the point that they can immediately recognize off-key or odd pronunciations, and local dialects and foreign accents, and who develop the habit of learning and maintaining the language through alphabetic script, are apt to visualize the sounds in terms of the script. And when they internalize or recall odd pronunciations of a word, they are likely to "spell" the word oddly. Hence some of the odd spellings in printed and web sources.

Some reasons some speakers of English have trouble with some Japanese words

English is notorious for its resistance to the repetition of some vowels but especially "o" (oh). Hence "Yokohama" and "Yokota" commonly come out "Yokahama" and "Yokata" or even "Yakota" in the mouths of natives speakers of English who are not familiar with Japanese.

English speakers have less trouble repeating "ah", hence the shift of "oh" to "ah". Japanese "kimono" -- key-moh-noh -- has so commonly been anglicized (accented or corrupted by English) as "kimona" that this spelling appears in some dictionaries and in the fashion industry. However, English speakers usually don't have a lot of difficulty with "yukata" (you-kah-tah) or "katakana" (kah-tah-kah-nah) because English is kinder to repetitions of "a". English speakers unfamiliar with Japanese segmentation, however, are likely to syllablize "hiragana" as "HERE-rah-GA-nah" rather than "hee-rah-gah-nah".

Japanese sounds

A non-native speaker of Japanese with a good ear -- who can memorize and write in diction the kana script (hiragana and katakana) used to represent the 46 standard mora, and the limited number of ways in which they are combined to create other sounds, which requires only a few days -- can correctly write whatever Japanese words he or she clearly hears. The only "spelling bees" in Japanese involve the writing of Chinese characters or graphs.

Spelling English words is a challenge to native speakers and non-native learners of English alike, for they have to learn multiple possible spellings of each sound, and memorize the specific spellings of each word.

Japanese sounds -- vowels and consonants -- are easy, and sound combinations are very regular. Unlike English, a syncopated stess-based language, Japanese is practically metronomic. Whereas English gives more time to stressed styllables (with full vowels) and less time to unstressed syllables (with reduced vowels), Japanese allocates about the same amount of time to each mora, meaning a vowel (V), consonant-vowel (CV), or terminal consonant (-C). Stress (emphasis by strengh) as a linguistic (rather than emotional) quality is important in English, whereas pitch (level or frequency) is more characteristic of Japanese.

Both "Toyota" and "Nikon" in Japanese are 3-morae words -- "to-yo-ta" pronounced "toe-yo-tah" and "ni-ko-n" pronounced "knee-koh-ng" or "knee-kohng" (not "knee-cone"). In English, though, these words are anglicized (syllablized and stressed) as "toy-OH-tah" and "NIGH-con" -- "nigh" as in "high" and "con" as in "convict".

The 5 vowels in Japanese are a-i-u-e-o pronounced ah-ee-oo-eh-oh -- approximately "a" as in "awe" and "saw", "i" as in "he" and "she", "u" as in "you" and "sue", "e" as in "met" and "set", and "o" as in "boat" and "so" -- but all short and crisp whether alone or following a consonant. When long they are doubled. Pitch and stress are different matters.

The consonants k/g, s/z, t/d, h/p/b, n, m, and r appear initially before all the vowels a, i, u, e, and o -- ka, ga . . . ra -- ko, go . . . ro.

The consonant y used today only with a, u, and o. In the past, it was also used with e, and may be found in fossilized romanizations like "yen" and "Inouye".

The consonant w is today limited to a and o. Historically, it was also used with i and o, and is sometimes found in fossilized romanizations. Just as older spellings of English words can be used to "antique" a word, ye, wi, and we are sometimes used, along with other historical forms, to create the illusion of older language.

The pronunciation of terminal -n is "-ng" but it will be "-n" or "-m" if followed by "t" or "m" -- hence "wangan" (gulf) will be wang-gang, "wantan" (wanton soup) will be wan-tang, and wanman (one man) will be wam-mang, while "wanman basu" (one-man bus, i.e., a bus with only a driver and no conductor) will be wam-mam-ba-su. Think of how the "n" in the negative prefix "in-" assimilates with the following sound in English -- "regular" (irregular), "legal" (illegal), "possible" (impossible).

Japanese "su" is reduced in some words in some dialects, hence "desu" is "de-su" in Kyoto and "des" in Tokyo. "Suki desu" (I like [something]) is "Ski des" in Tokyo but "Su-ki de-su" (or "su-ki do-su") in Kyoto. "Yo-ko-su-ka" is usually "Yokoska" in the Kanto (Tokyo-Yokohama) area, hence the tendency of some English speakers to spell it this way, while people in the Kansai (Kyoto-Osaka) area who haven't learned the place name through the ear may read ���{�� (�� yoko �{ su �� ka) (�� yo �� ko �� su �� ka) as 4 morae.

Other linguistic effects in Japanese result in the doubling of some consonants -- kk, ss, tt, pp. A few other sounds also shift in specific environments. On the whole, such effects are fairly predictable.

The "f" in the Hepburn romanization of "h" as in "ha, hi, fu, he, ho" is labial (between opposed lips), not dental-labial (upper teeth on lower lip). Hence the "f" of "Fuji" is not like the "f" of "fool" but more like "who" made with the lips.

Some originally non-Japanese consonants have been accommodated by Japanese orthography. The best example is the increasing use of "v", which until recently was represented by "b".

Vietnamese, Korean, and Chinese

In this history of Kishine and the 106th, I have sometimes shown Vietnamese, Korean, and Chinese words or phrases in various scripts. These 3 languages have something in common in that none are linguistically related to Chinese.

Among these 4 languages, including Chinese, only Japanese and Korean are possibly related to each other linguistically. However, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese are commonly related to Chinese through their histories of extensive borrowings from Chinese, and their use of Chinese writing before they developed native or other writing systems.

Chinese

Chinese is written in Chinese graphs, which I generally represent in the Wage-Giles or Pinyin systems of romanization, depending on the source.

Korean

Korean today is written mainly in hangul, a phonetic (nearly phonemic) script, but may include a few Chinese (Sino-Korean) graphs. In the past, Korean writing was a heavy mixure of hangul and Chinese graphs, just as Japanese today continues to make extensive use of Chinese (Sino-Japanese) graphs along with moraic kana (both hiragana and katakana) script. I have generally represented Korean words in the McCune-Reischauer system of romanization.

Vietnamese

Vietnamese is today entirely represented in an alphabetic script first introduced in the 17th century, then more fully developed and implemented in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Until then, Vietnamese was written in Chinese graphs, comparable to the way Korean and Japanese made use of Chinese graphs, both to represent Chinese words in Vietnamese, and to represent the sounds of Vietnamese words.

Like Korean and Japanese, Vietnamese is linguistically unrelated to Chinese, but like Korea and Japan, Vietnam came under the influence of China and Chinese writing, long before it had a writing system of its own. Hence, historically, the use of Chinese (Sino-Vietnamese) graphs in what is sometimes call "Siniform" writing but which I call "Sinific" writing.

In this history, mostly from my own interest, I have shown the Chinese (Sino-Vietnamese) graphs for some Vietnamese personal names, place names, and formal expressions. I do not speak, and cannot read or write, or otherwise understand Vietnamese. But some Sinific Vietnamese words and expressions make sense as Sinific words and expressions.

"Vietnam" (�z��) means a country "south (�� nam) of Viet (�z)" -- "Viet" being a country that existed in the southern part of early China, immediately north of the present border between Vietnam and China. Migrations south from China resulted in Chinese influence and even control over the northern part of what is now Vietnam, similar to the influence and control that China excercised over Korea at times in its long and convoluted history.

"Vietnam" did not emerge as a name until around the 16th century. Before that, the names of the northern area of what is now Vietnam were Annam (����), which goes back to the 7th century, and Tonkin (����), which was an alternate name of the area, and of the capital city that later became Hanoi (��內). Depending on the period of history, and the government or governments in control of the area that became Vietnam, "Annam" has also referred to its central part, its central and southern parts, and even its entirety.

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), the northern part of what is now Vietnam was a province of China called Annam (����). During the 10th century, Annam broke away from China but remained closely influenced by China, which attempted at times to reclaim the area as a province.

The name of the capital of ancient Annam was at times Tonkin (����), which some people used to refer to Annam itself. Tonkin -- also Tonking, Tongking, and Dong Kinh -- is the Sino-Vietnamese pronuciation of ����, which means "eastern capital". In Sino-Japanese, the name can be read Tōkyō or Tōkei, or even Tōkin.

The imperial capital of Japan for over a millennium, from the Heian period (794-1185), which overlapped with the Tang period and China, to the end of Tokugawa era (1603-1868), was Kyōto (���s). In 1868, the city of Edo (�]��) became the capital, and Edo was graphically renamed ����, which some people read Tōkyō and others Tōkei. Both names appear in kana representations (such as furigana on woodblock prints) and alphabetic representations (such as postal frankings), but Tōkyō quickly became the standard name of the city.

Because ���� was historically associated with Vietnam, some publishers in Japan graphed the name of the new capital of Japan ���� instead of ����, using �� instead of ��. See Tonichi mastheads: The character of calligraphy for details.

Chinese characters were still evident in Vietnam at the time of the Vietnam War. I specifically ask a friend of mine who was then in Army and serving in Vietnam as an interrogator. See Andy Fountain (below) for his observations of Chinese calligraphy.

Cultural stereotypes

Don't expect a lot of talk about "Japanese culture" in my telling of the history of Kishine and the 106th in Yokohama. What little I say about life in Japan is intended only to clarify the meaning of something that comes up in one of my stories.

My understanding of "culture" is not what most people think of when they use the word. In my view, there is really no such thing as "a" culture in any country. "Japanese culture" is a figment of "culturalist" imagination that feeds "cultural determinism" -- the belief that a nation of people "are" whatever they are perceived to be "because" they are products of a "common heritage".

"Heritage" is ultimately a personal matter and comes mostly from family and other very local communal experiences. No humans share a heritage so "common" that they aren't first humans and second individuals. "Cultural" sharing is relatively limited, especially in a country as geographically large and diverse as Japan.

Everyone born and raised in Japan -- and everyone who has just recently stepped off the boat or deboarded a plane from another country in Japan -- shares exposure to whatever elements of life they encounter and experience in Japan -- individually. Whether or not, and to what extent, a person is affected by what he or she experiences will depend on all manner of personal factors which may or may not be shared with others. Everyone in the same family can be, and usually will be, different in many ways -- never mind their exposure to a common environment. In real life, I find I have little use for cultural stereotypes.

In the end, you mediate only what you absorb and express. As you get older, the process of becoming acquainted with something new is a bit more conscious. Awareness of everything that has already become part of you inhibits spontaneous acceptance of something new. The old and the new become rivals for mediation.

Take, for example, shaking hands, or hi-fiving, or bowing. If you're used to making decisions about whether and how to shake hands, and whether and how to execute a hi-five or other such greeting or parting or acknowledgment, but not used to bowing, then bowing will probably require conscious effort. Should you shake hands or bow? Or both? At some point, though, such decisions become reflexive.

Until your responses to new conditions become second nature, you will find yourself negotiating between new and old choices and endeavoring to avoid being awkward in situations that you are not used to -- not yet "accustomed" or "acculturated" to. Eventually, though, the "new" becomes as familiar as the "old" and you accommodate the new as appropriately as the old.

After becoming reflexively "bicultural" with respect to social behaviors like "handshaking" and "bowing" -- each of which involves choices of the kind or degree of handshaking and/or bowing -- you will still have to deal with the different ways that others will approach or react to you, on a case-by-case, one-on-one basis. For in the real world, there is no such thing as a pervasive one-size-fits-all "Japanese culture" or "Japanese way" -- but only individuals who may be nationals of Japan but are first and foremost humans with personalities and idiosyncrasies before they are "Japanese".

Not all Japanese dance to the same music. And those who do dance to the same music are likely to do so differently for personal reasons. Hence you will notice that I do not speak of things like "the Japanese", because there are roughly 125 million Japanese, including myself. If you live here, and know a lot of people who have lived here all or most of their lives (which I prefer to "life"), you will recognize that everyone is an individual, and that individuality matters when it comes to things that matter -- like friendships, partnerships, and rivalries.

I can't think of a single thing that Japanese collectively do in such unison that they can properly be thought of as "the Japanese" -- or otherwise be the subject of declarations like "Japanese people love nature". This sort of grammar is typical of generalizations that undermine the ability to recognize the diversity and variety that one ought, from the start, to expect of a country of 125 million people. Even a population of 125 or a group of 12 or 13 Japanese would defy collective "they are" generalizations other than those like "They are nationals of Japan" in which you can be sure that everyone in the class in fact shares the same trait -- in this case, possession of Japan's nationality.

So my descriptions of Japan and Japanese are full of nuancing qualifications like most, many, some, a few, few -- and I eschew the temptation to reduce the complexities of life in Japan to lock-step, all-hearts-beat-to-the-same-drummer superlatives like "all" or "no one". I reserve global cut-and-dry, black-and-white generalizations and superlatives for the very rare occasions when they might actually be warranted. I drive editors who want to keep things simple and save words crazy.

Basically, I am not especially interested in what most people consider "culture". My settling in Japan, and my acquisition of Japanese nationality, were not motivated by a desire to learn more than a survivalist minimum about Japanese foods, Japanese religions, Japanese festivals, Japanese music and dance, temples and shrines, fashions and arts, and the myriad other "things Japanese" that consume the attention of many people, Japanese and foreigners alike, and have inspired tens-of-thousands of books in Japanese and thousands in English and other languages. I take "things Japanese" in stride -- as part of my daily background and occasionally my foreground.

What little I have learned about such things has been through the agency of curiosity about the human condition in Japan -- what motivates ordinary people, as living beings, in their struggle to make sense of their lives as individuals and social animals, blessed or cursed with the capacities and qualities we call "human" in order to differentiate ourselves from monkeys, mice, millipedes, and monsters.

People ask me if I get along with my "Japanese neighbors" or if I have a "Japanese wife" or "mixed kids". I say I have neighbors -- everyone who lives in a neighborhood anywhere in the world has neighbors -- and most of my neighbors are Japanese. But I have no "Japanese" neighbors. I have only neighbors. And of course I get along with them. Isn't that what neighbors are for? To get along with? Some people then say, "I meant do they accept you?" To which I say, "I accept them, and that's all that matters to me. Whether someone accepts me is their business."

I had a wife -- a female spouse, which because we were legally married made her my wife, which is not to say that I possessed her. And she happened to be Japanese. But she was just a woman, just my wife, just the mother of our -- her and my -- children. We were just another couple, just another family.

My children, like every child ever born between two parents, are mixtures of their parental genes. I'm a mixture of my mother's and father's genes. Their mother is a mixture of her mother's and father's genes. They are thus mixtures of the genes of 4 grandparents, 8 great grandparents, 16 great-great grandparents, and 32 great-great-great grandparents. So, yes, my kids are definitely very mixed.

Journalists and scholars -- I used to say "even scholars" but along the way I realized there is no reason why scholars should know better -- from America or Germany or Korea have asked me my views of "Japanese suicide", having gotten the impression of things I've written that I am an "expert" on the subject. I quickly clarify that I have been only a "student" of suicide generally -- "human suicide" including "suicide in Japan" -- but not of "Japanese suicide". There is no such thing as "Japanese" suicide for all the reasons I have suggested in my writing on suicidal behaviors. All suicidal acts are different. All are motivated by personal human factors. Most writing on suicide as something determined by "culture" are not about suicide as a behavior, but about how people who don't commit suicide deal with suicide. Japan is far from being the only country in the world in which some dramas, films, and novels have depicted suicide as an alternative to remaining alive come what may. Such representations of suicide are in fact fairly universal. Moreover, entertainment and other media in Japan have also, over the centuries, presented suicide as something that one should not resort to. Other than in cases where "self-execution" was a prescribed punishment for members of the warrior caste who violated laws that applied to them, taking ones own life in Japan has always been a personal choice -- even when done in desperation or when under duress.

I didn't used to think this way. It took me a few years to rid myself of the "national character" stereotypes that were common in my own education half a century ago, and which most teachers in schools everywhere are still spreading. Stereotypes have the single merit of keeping things simple so you don't have to think. Belief that national "culture" or "blood" determine character is a thought-terminating concept -- if such thinking can be dignified as a "concept". Expecting that someone who happens to be Japanese knows something about "tea ceremony" or "kabuki" or "anime" or "Buddhism" -- or has an interest in such things -- is to risk being disappointed -- as disappointed as a zealous Japanese student of English literature will be to learn that their American seatmate on a trans-Pacific flight has never seen a Shakespeare play and may not even know where Shakespeare lived, or recall what they read by Hemingway. And they might not know, or care to know, about why there are U.S. military bases in Japan.

The sort of allegations I have made here fly in the face of "conventional wisdom" practically everywhere. I will humor "culture" talk to be polite, but not for long. I take advantage of, or create, openings in which I can get down to the business of warning people coming to Japan that people in Japan are no different from people anywhere. They love and kill each other, themselves, and others, and eat or starve, and laugh or cry, for essentially the same reasons that, say, British, Germans, Chinese, Nigerians, Filipinos, and Americans do -- and for the same reason, that they are human -- and no two Japanese, no two humans, are the same.

Wars like the Pacific War, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War should be proof enough that the only issues that really divide nations are the same issues that divide members of the same family or neighborhood -- territorial and economic greed and jealousy, exacerbated by the propensity to dehumanize each other. And dehumanization begins with "group-think" stereotypes.

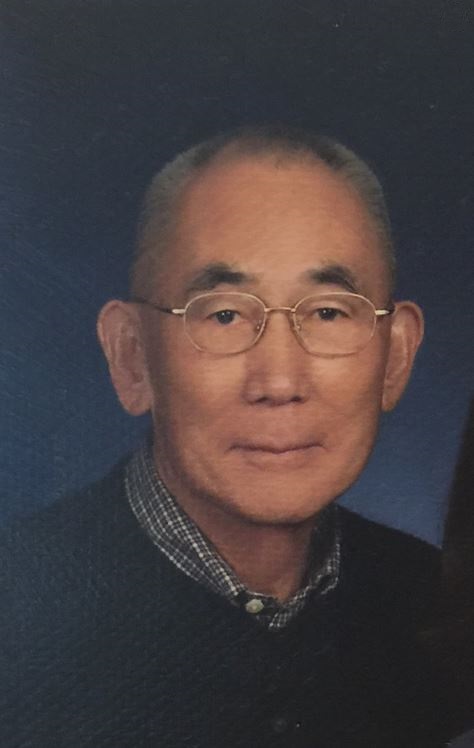

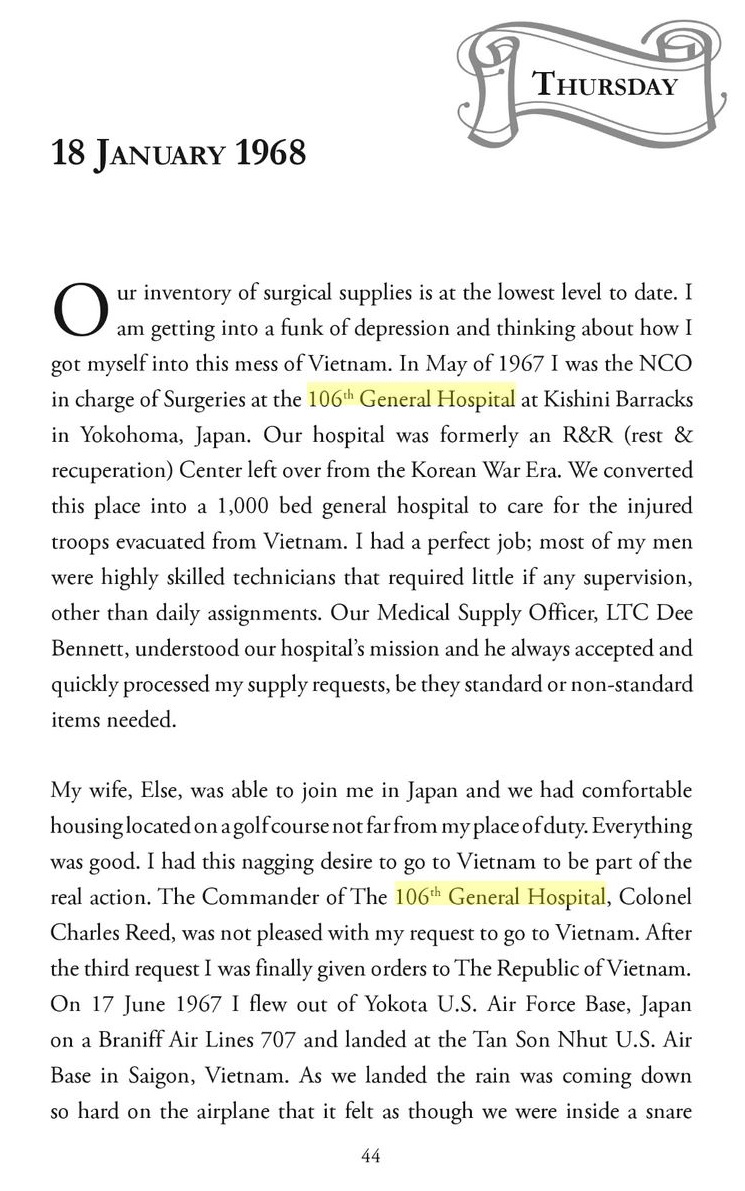

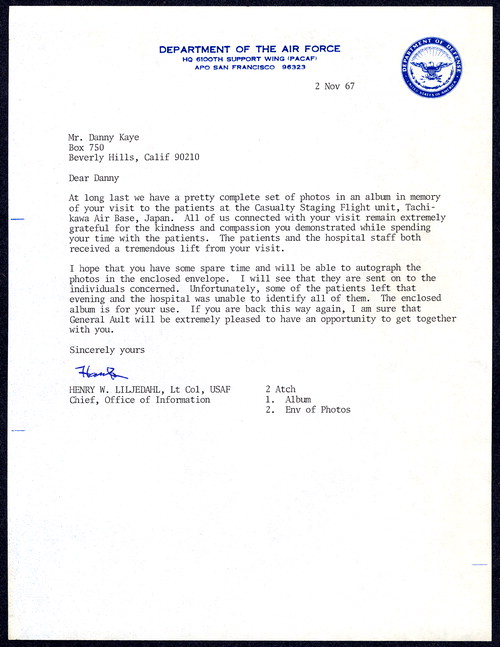

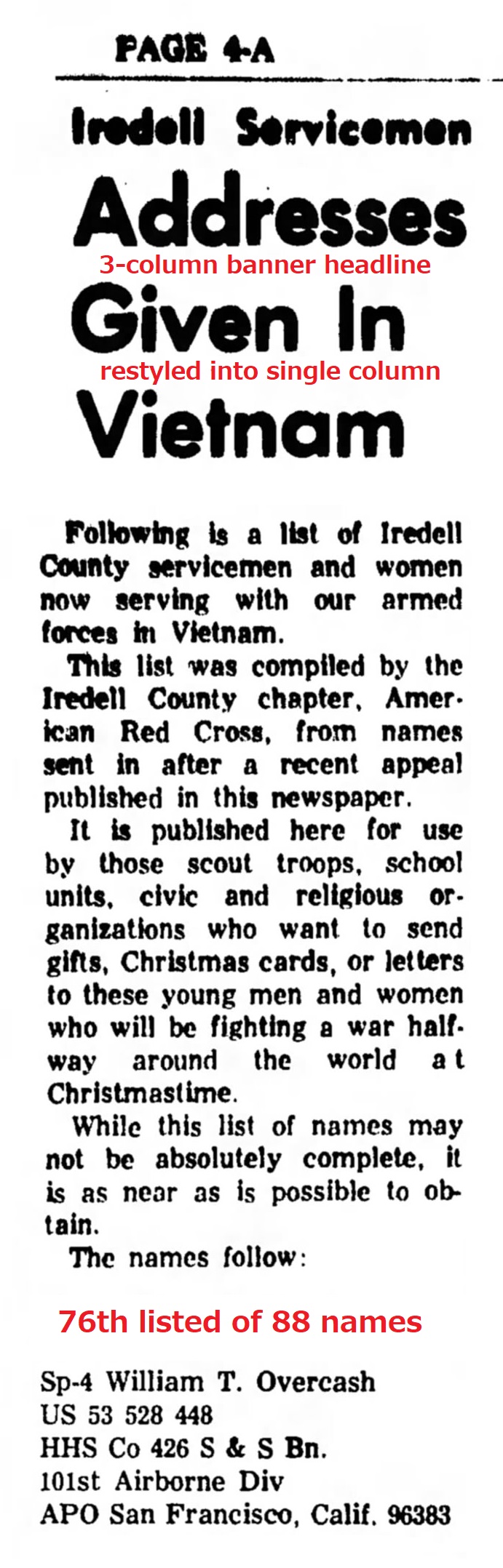

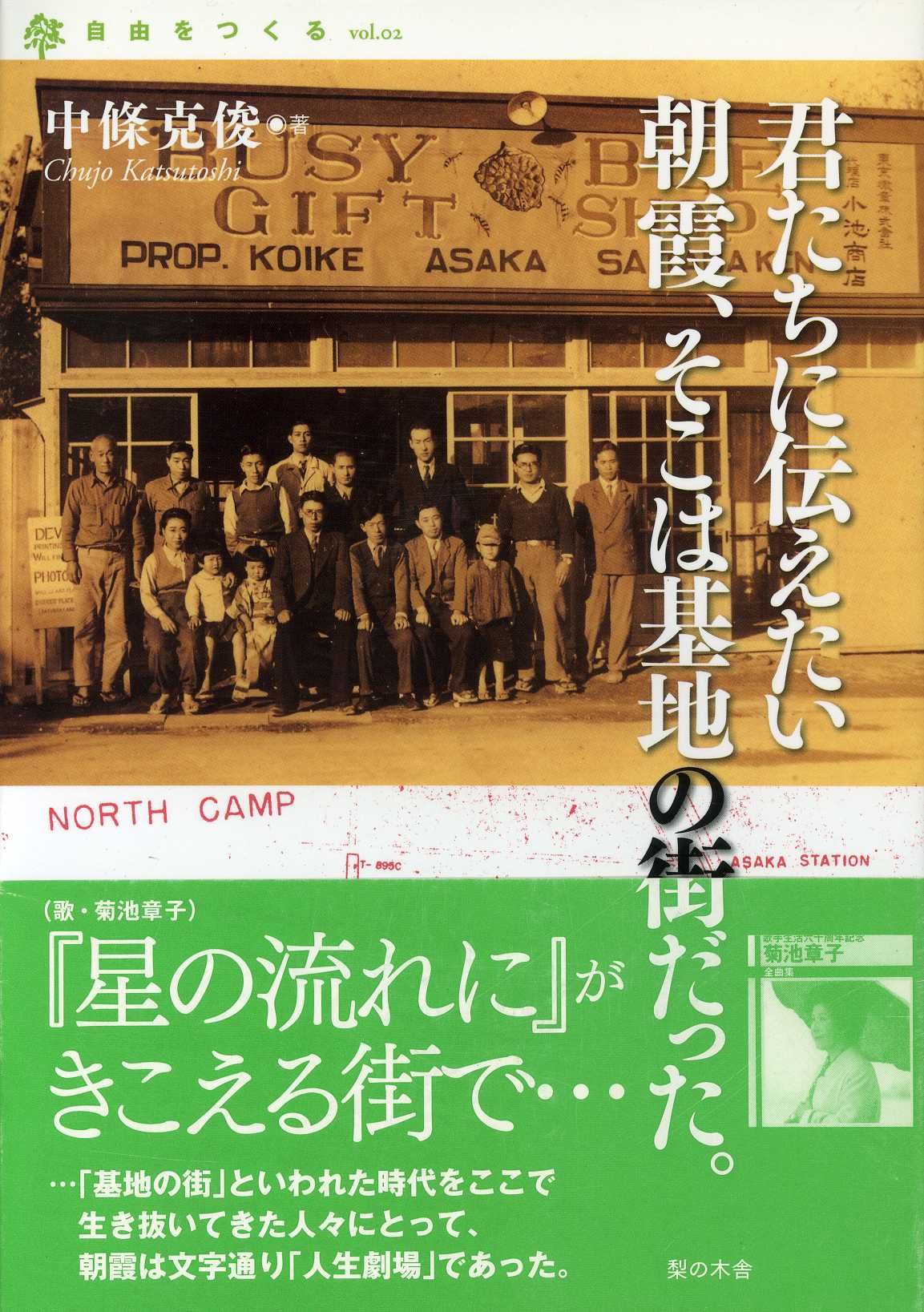

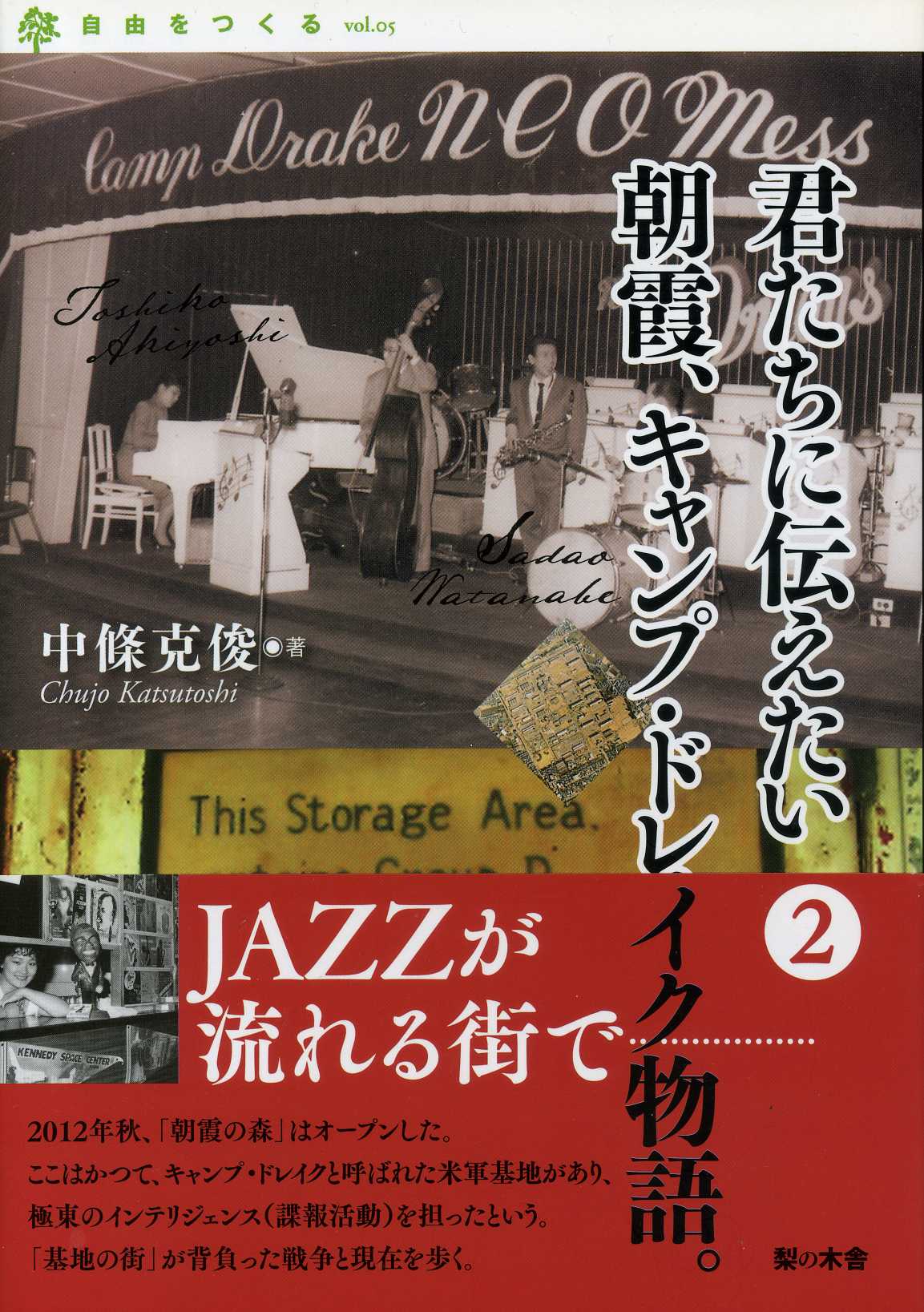

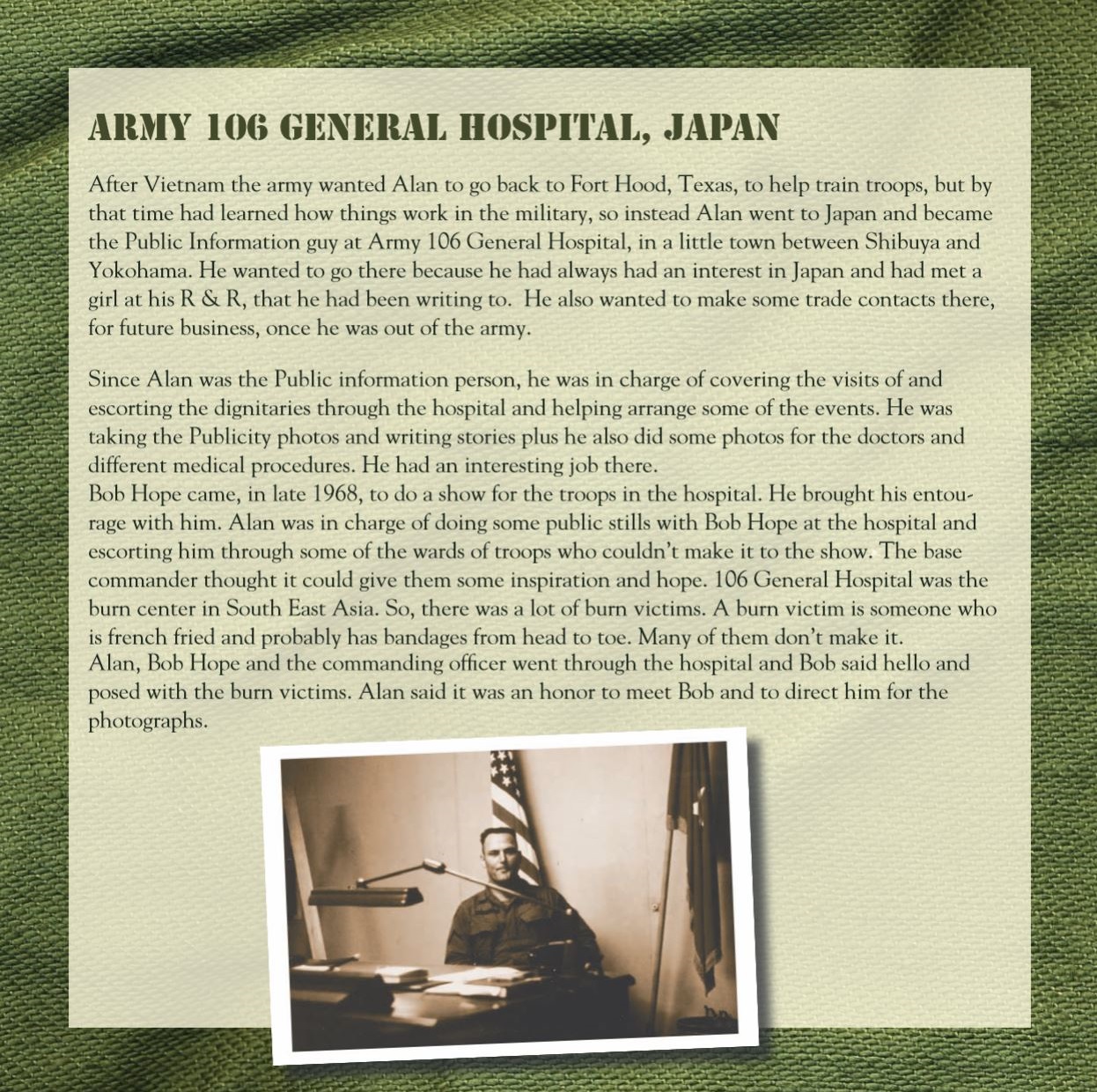

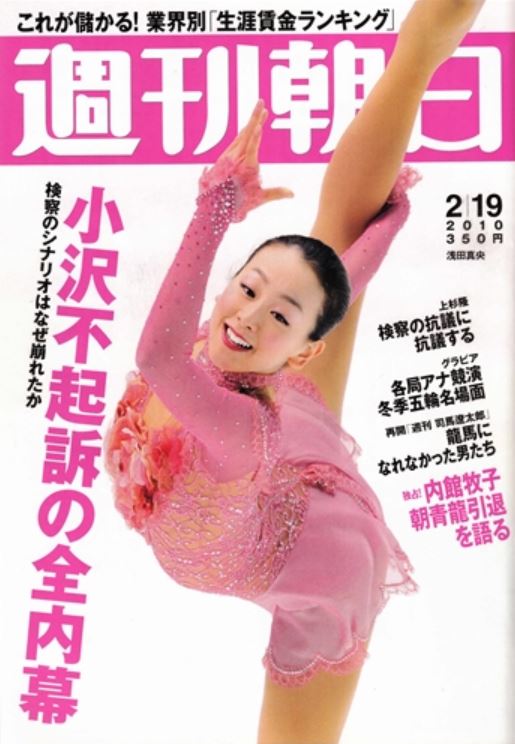

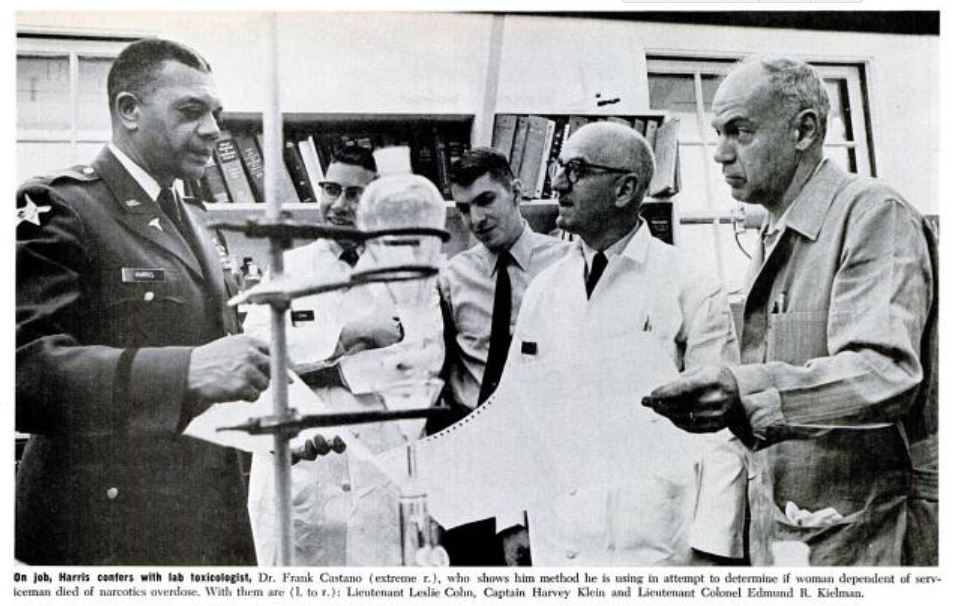

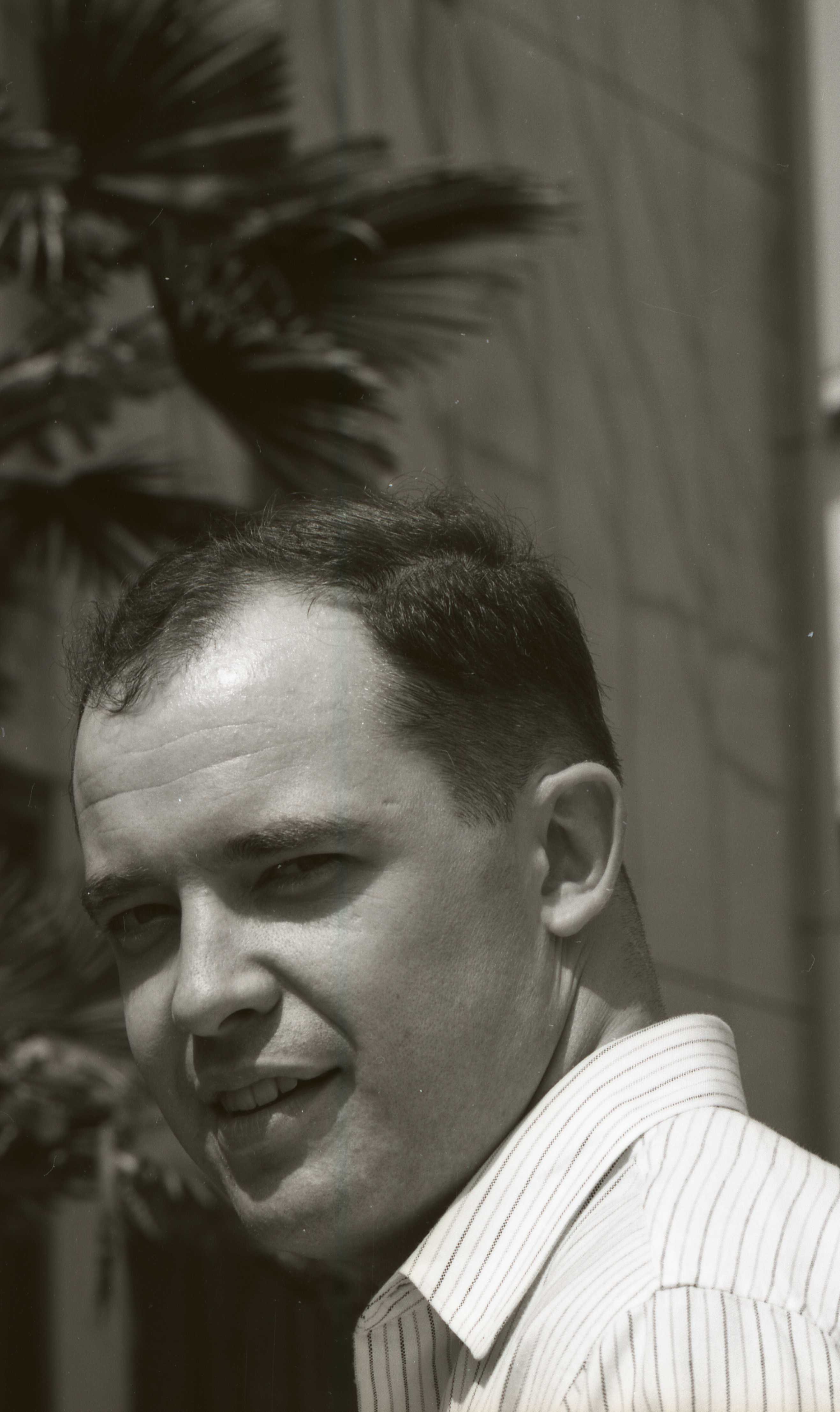

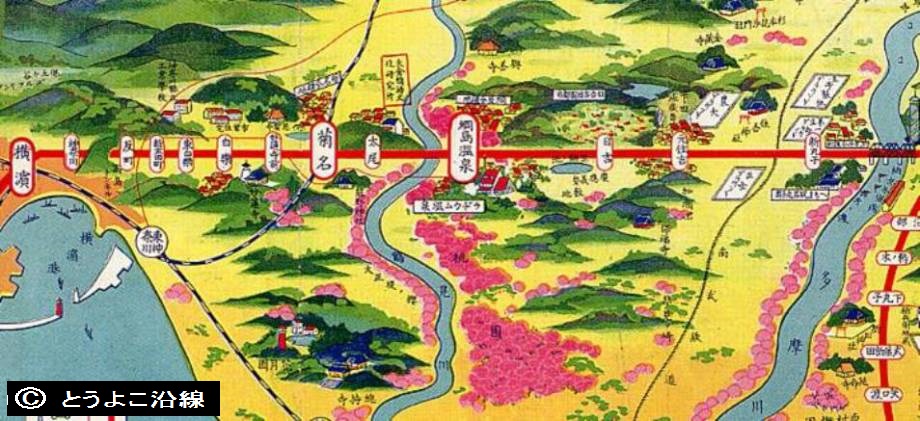

2017 Kanagawa News article on Kishine Barracks and 106th General HospitalIn July 2017 I received email from Yuuki Takahashi (Takahashi Yūki �����Z��), an editor with Kanagawa News (Kanagawa shinbun �_�ސ�V��), stating that he had seen my webpage on Kishine Barracks (the original shorter version of this expanded edition) and wanted to interview me for an article in a series he was writing on the impact of the Vietnam War on Kanagawa prefecture and the continuing effects of the presence of U.S. Forces in Japan on the prefecture. He came to my home, he ask me questions about my military service and experiences at Kishine, my views of the Vietnam War, and my opinions about a number of political issues related to how wars are remembered, and whether or not Kishine's role in the Vietnam War should be remembered. The article was published as the first of three from 8 September 2017. Mr. Takahashi shared the galleys with me to solicit corrections and other feedback, which he incorporated into the final copy. The photograph he took of me at my home was featured with the article, which also ran one of my photos of a helicopter lifting off the pad at Kishine. The article concluded with the observation that 50 years after I had been at Kishine Park as an American, I had visited Kishine Park as a Japanese national. See William Wetherall (1965-1966, 2016): "What war, what barracks, what hospital?". |

106th General Hospital official report (1969)The following texts and tables are reproduced from a copy of an official guide to the 106th General Hospital, compiled in 1968 and early 1969 and published in 1969. Most of the data is from 1968, but the personnel data is dated 9 January 1969. From paper to hypertextThe received report had 13 pages in addition to a cover. I produced the html versions shown below by first making jpg scans of each page and then creating text files by scanning the jpg images with OCR software. I then formatted the text in html and edited the text against the text of the the original report. All [bracketed remarks], information highlighted in red, and boxed comments are mine. Illegible text is represented by bracketed ellipses [ . . . ]. AcknowledgmentsI received a copy of the report from Michael Caines, who had been a burn patient at the 106th. He had received his copy from Harold Rubin, who received an original copy at the time it was issued, when he was in charge of the 106th's Pharmaeceutial Services I came across Michael's name on an Internet forum in which he stated that he had a copy of the report. I contacted him by email, and he sent me a copy and put me in touch with Harold. I am grateful to both men for sharing their time and experiences with me. Both Michael and Harold arrived after I left, and I have met them only through email. Michael had left before Harold arrived, but the two men later crossed paths and remain friends. As a laboratory technician whose rounds at times included the burn ward, I would probably have drawn Michael's blood had I been there when he was. Even if Harold had been there when I was there, I would not have had reason to make his acquiantance, for the medical librarian I liked didn't move with the medical library, from the laboratory building to the Hospital Clinic building, where the pharmacy was located, until after I left. See Michael Caines (1967-1968) and Harold Rubin (1968-1970) below for more about their service and experiences. |

Unit history

106th GENERAL HOSPITAL

UNIT HISTORY STATEMENT

The 106th General Hospital was originally activated at New Oreleans [sic = Orleans], Louisiana, on 15 July 1943, as the 286th Station Hospital. The unit was activated at 500 beds, expanded to 750 beds in ten days, and had 1,000 beds by December 1943. On 23 December 1943, the unit was redesignated the 106th General Hospital. The hospital underwent basic unit training at Fort McClellan, Alabama through June of 1944, at which time it was deployed to Britain where it was stationed outside London. The unit actively supported the European Theater during the Second World War, handling a balanced load of medical and surgical cases with a specialty in neurosurgery. The unit was returned to the United States in August 1945, and assigned to Camp Sibert, Alabama, where it was deactivated on 4 October 1945.

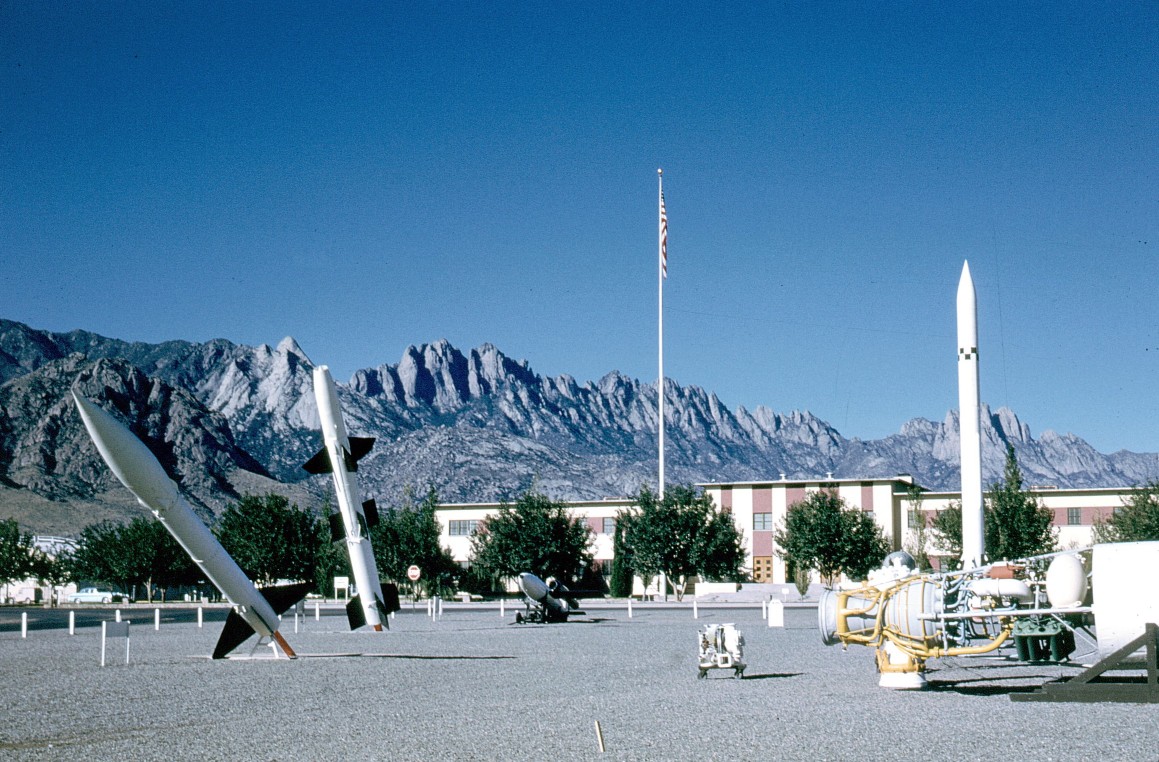

The unit was allocated to the Regular Army on 17 November 1959, and reactivated on 1 December 1959 at William Beaumont General Hospital, El Paso, Texas. During the period from activation until it was alerted for overseas movement, the unit underwent parallel training with William Beaumont. From 1959 through 1965, the hospital underwent several T0&E [Table of Organization and Equipment] reorganizations and changes and STRAF [Strategic Army Force] re-classifications. On 2 September 1965, the unit was allerted [sic = alerted] for deployment to an overseas area. The personnel of the hospital traveled from El Paso to Yokohama on four aircraft during the period from 12 through 16 December 1965. On 15 December 1965, the medical assemblage arrived at North Pier, Yokohama. The hospital was operational 72 hours later on 18 December.

During the first two and one-half years of operation the hospital has admitted and treated over 16,000 patients evacuated from Vietnam. The primary workload of the hospital has been surgical with a specialty as the Burn Center of the Far East.

Meritorious Unit Commendation On 2 December 1969, a few months after the 106th published its report, the Department of the Army awarded the 106th General Hospital a Meritorious Unit Commendation in recognition of the services it provided "in support of medical care for patients evacuated from the Republic of Vietnam during the period December 1965 to December 1968." Similar commendations were also given to the 249th General Hospital and 406th Medical Laboratory. See Department of the Army, General Orders No. 75, 2 December 1969 for the full citations.

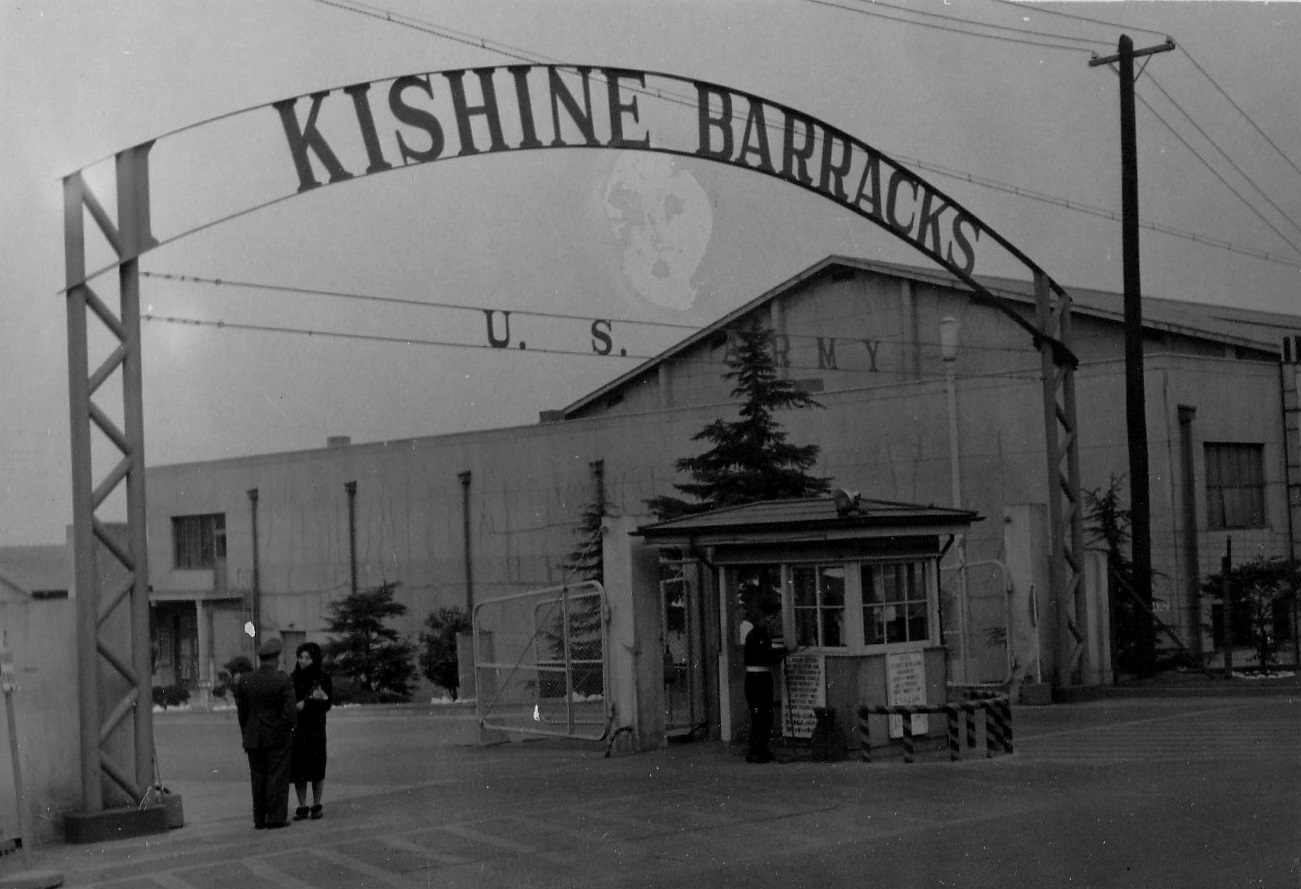

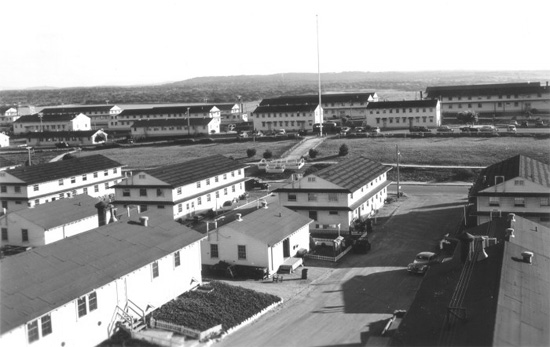

Installation

INSTALLATION INFORMATION

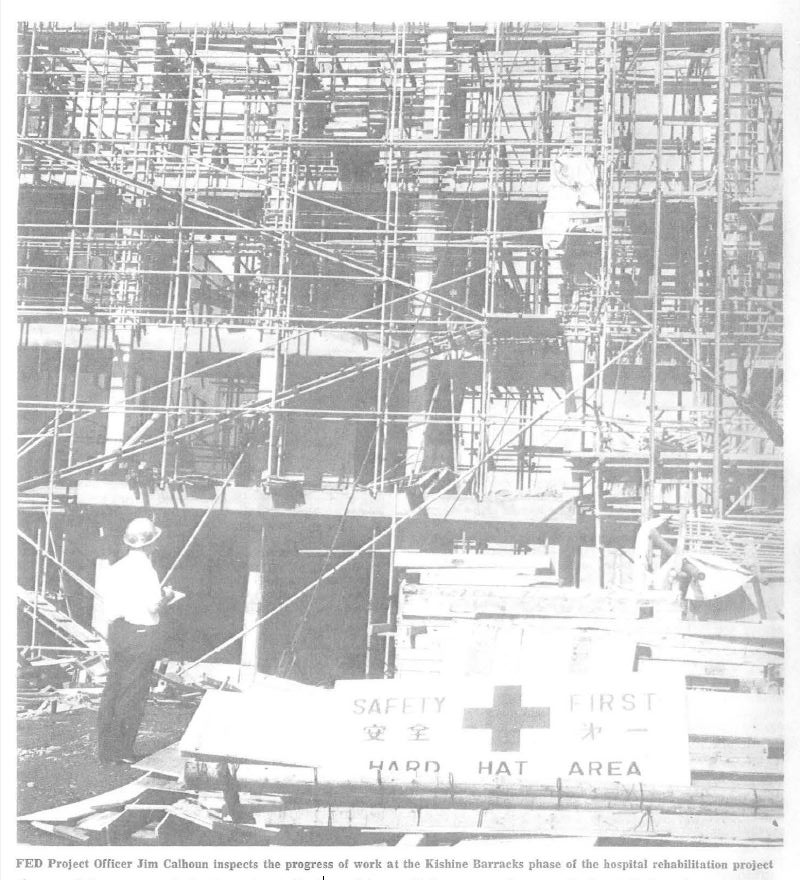

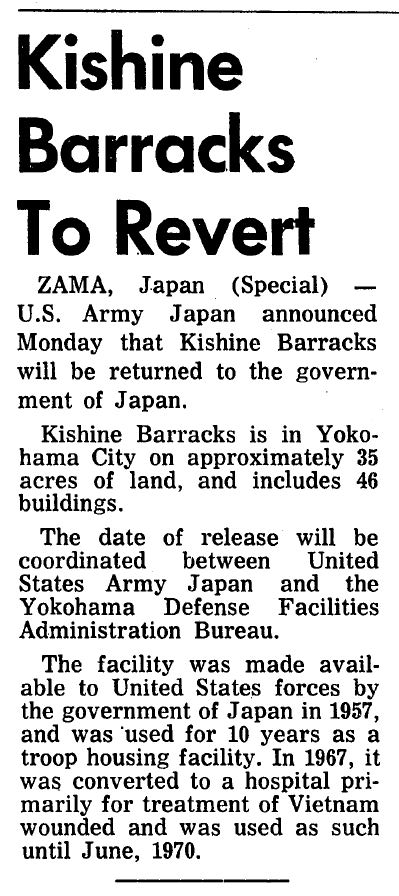

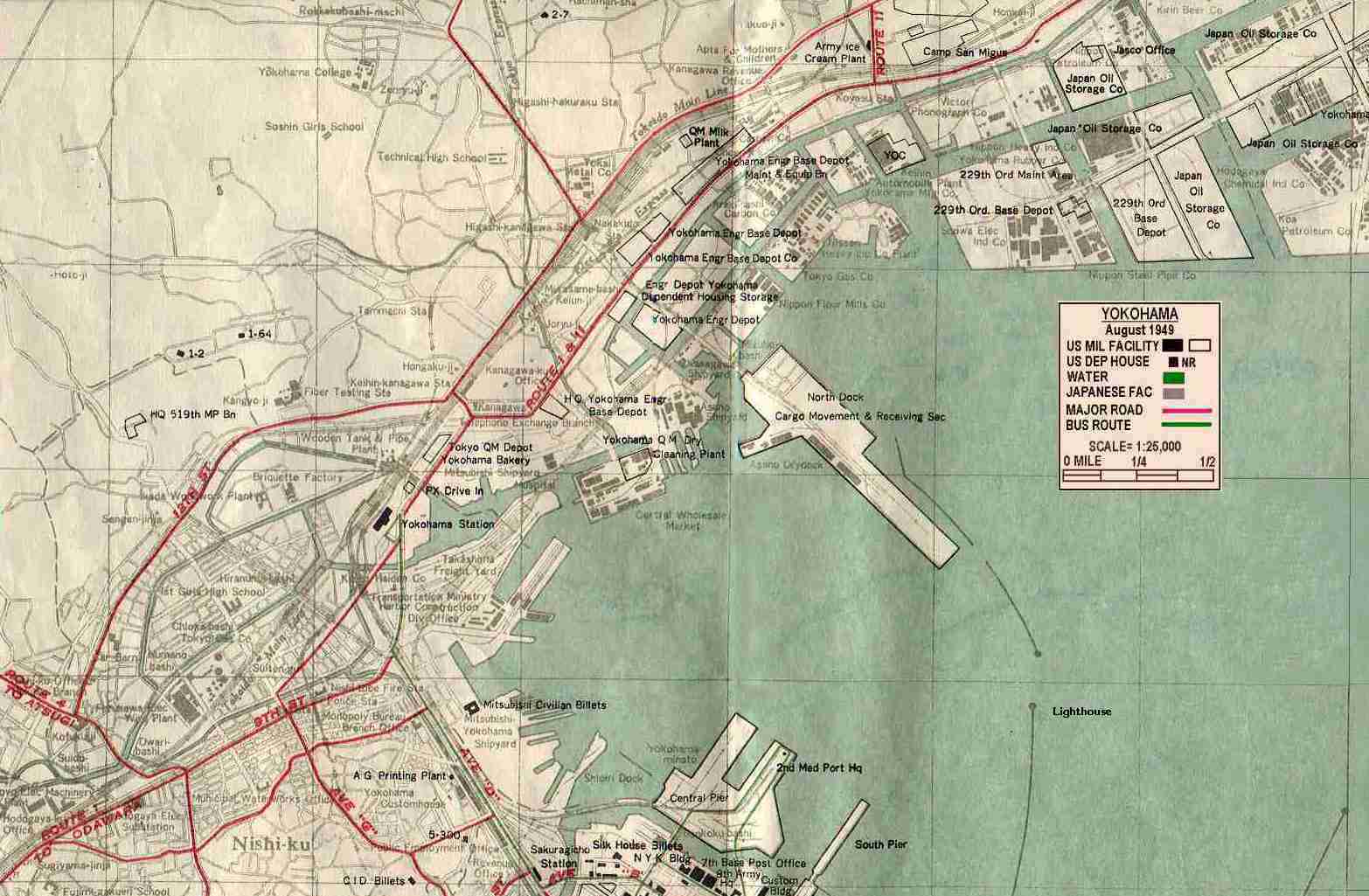

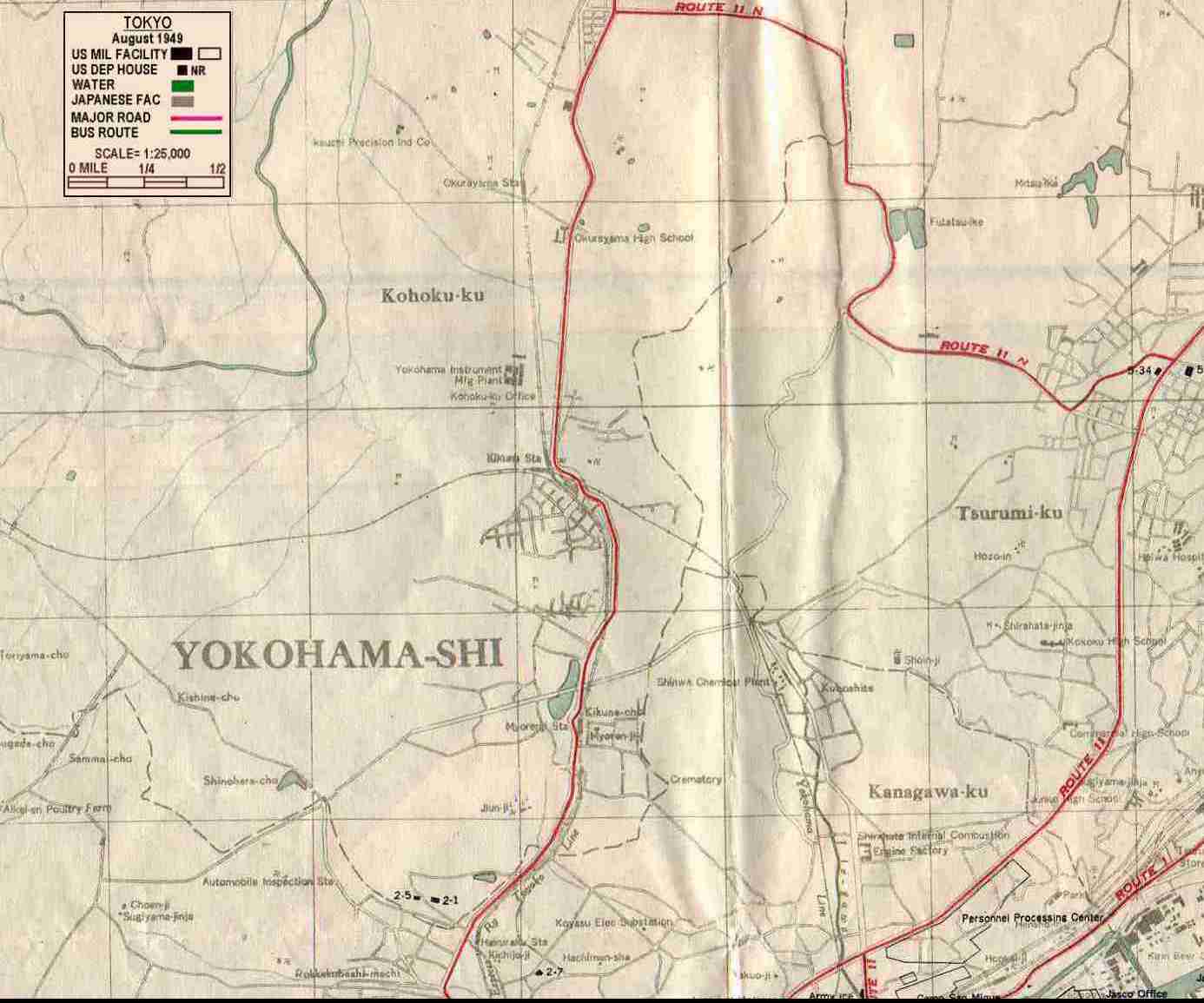

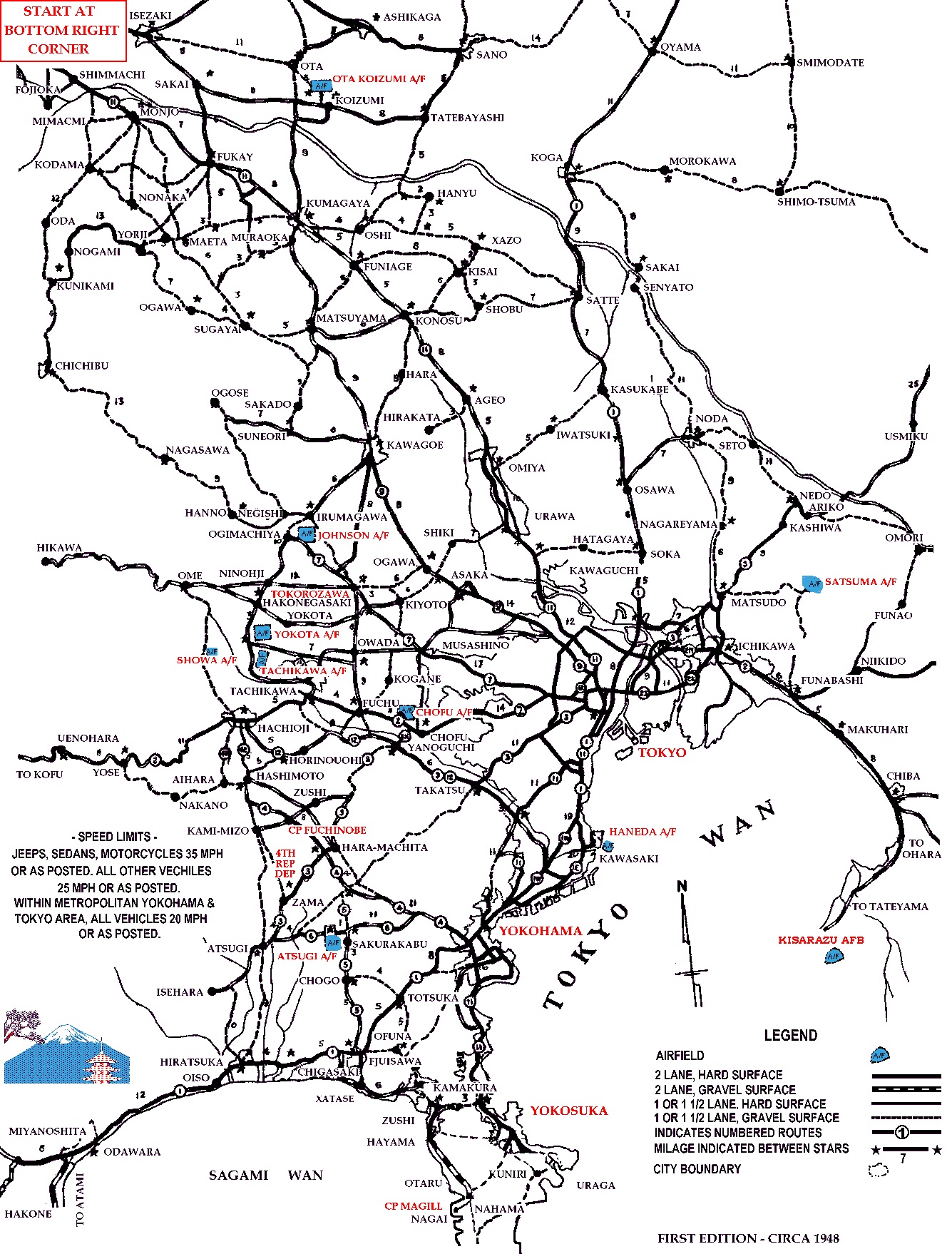

KISHINE BARRACKS -- YOKOHAMA, JAPAN

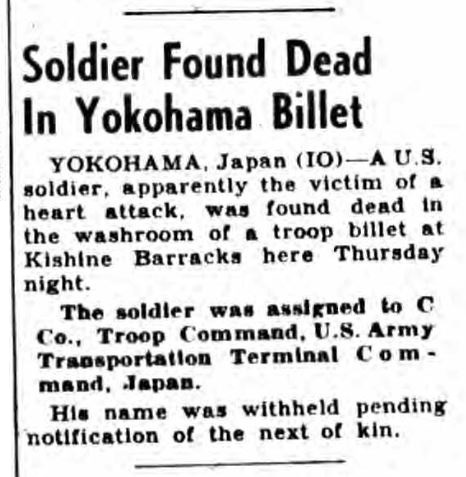

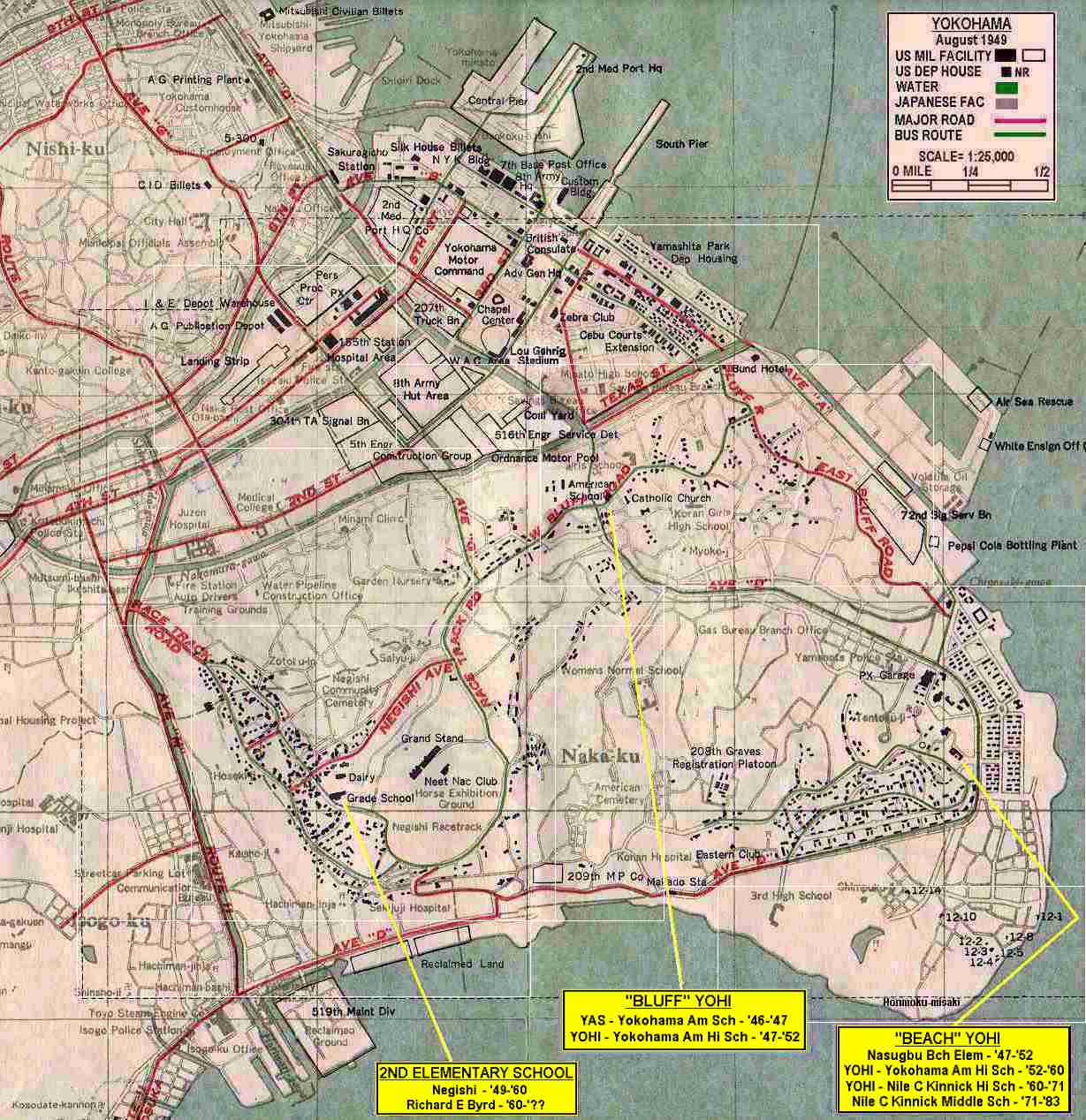

HISTORY: Kishine Barracks was constructed in 1956 and 1957 on farmland owned by the Japanese Government. The installation was transfered [sic = transferred] to the U.S. Army on 1 June 1967 in exchange for some U.S. Forces property in the Tokyo area. It was originally occupied by Troop Command, Army Transportation Terminal Command, Japan and U.S. Army Personnel Center, Far East. On 15 December 1965 the 106th General Hospital replaced the Personnel Center, which moved to Camp Zama.

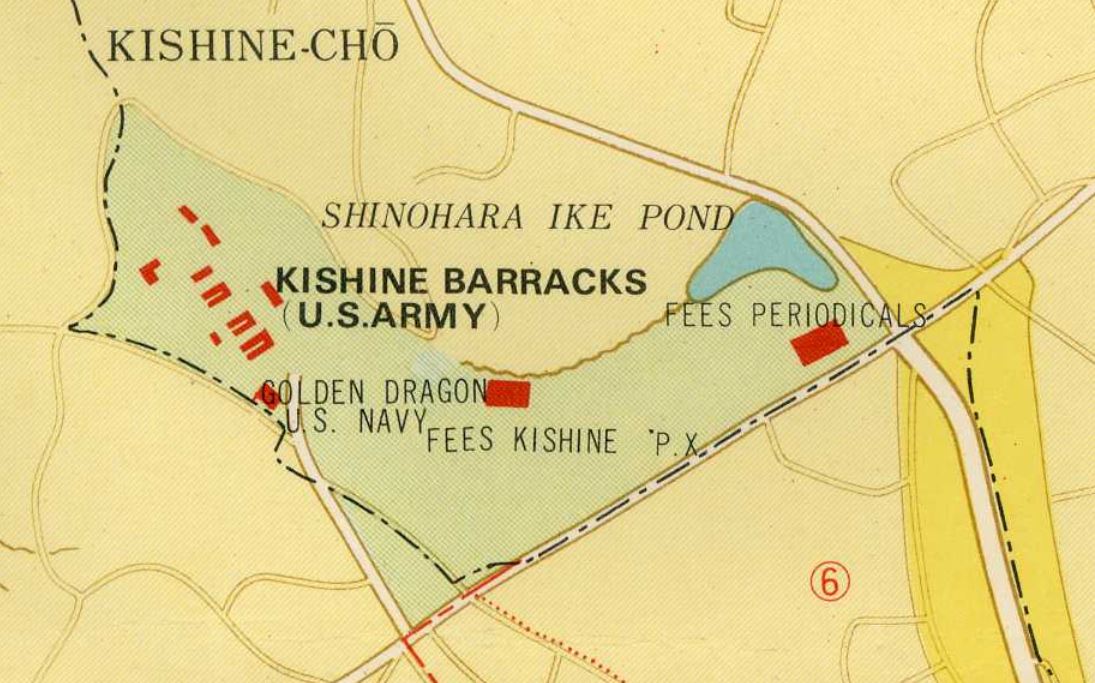

LOCATION: Kishine Barracks is located in Kanagawa Prefecture approximately 4 miles north of Yokohama and 17 miles south of Tokyo. The installation is 35 acres, triangular in shape, 0.37 miles wide and 0.18 miles long. National Highway #1 extends along the southeastern portion and National Highway #16 extends along the southwestern portion of the installation.

Latitude 35 29' N

Longitude 139 37' E

BUILDINGS: The installation consists of 18 permanent building with 325,865 square feet, and 20 semi-permanent buildings with 77,979 square feet. There are 2 temporary buildings with 167 square feet. Estimated replacement cost of land and buildings is $27,274,000. Annual maintenance and support cost is $276,300.

|

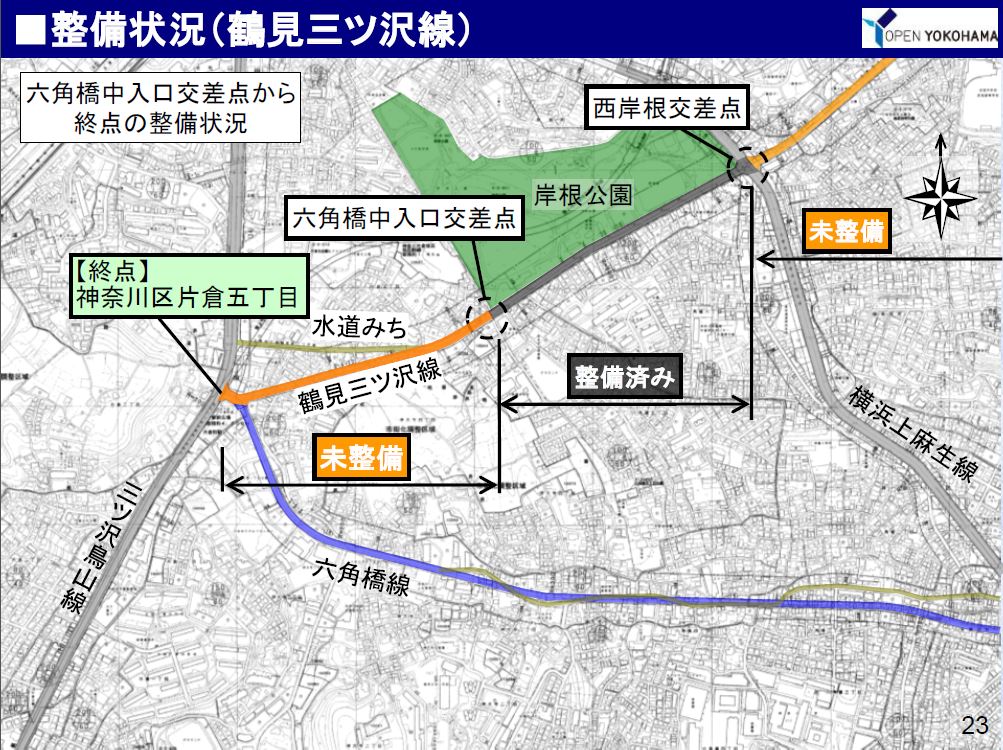

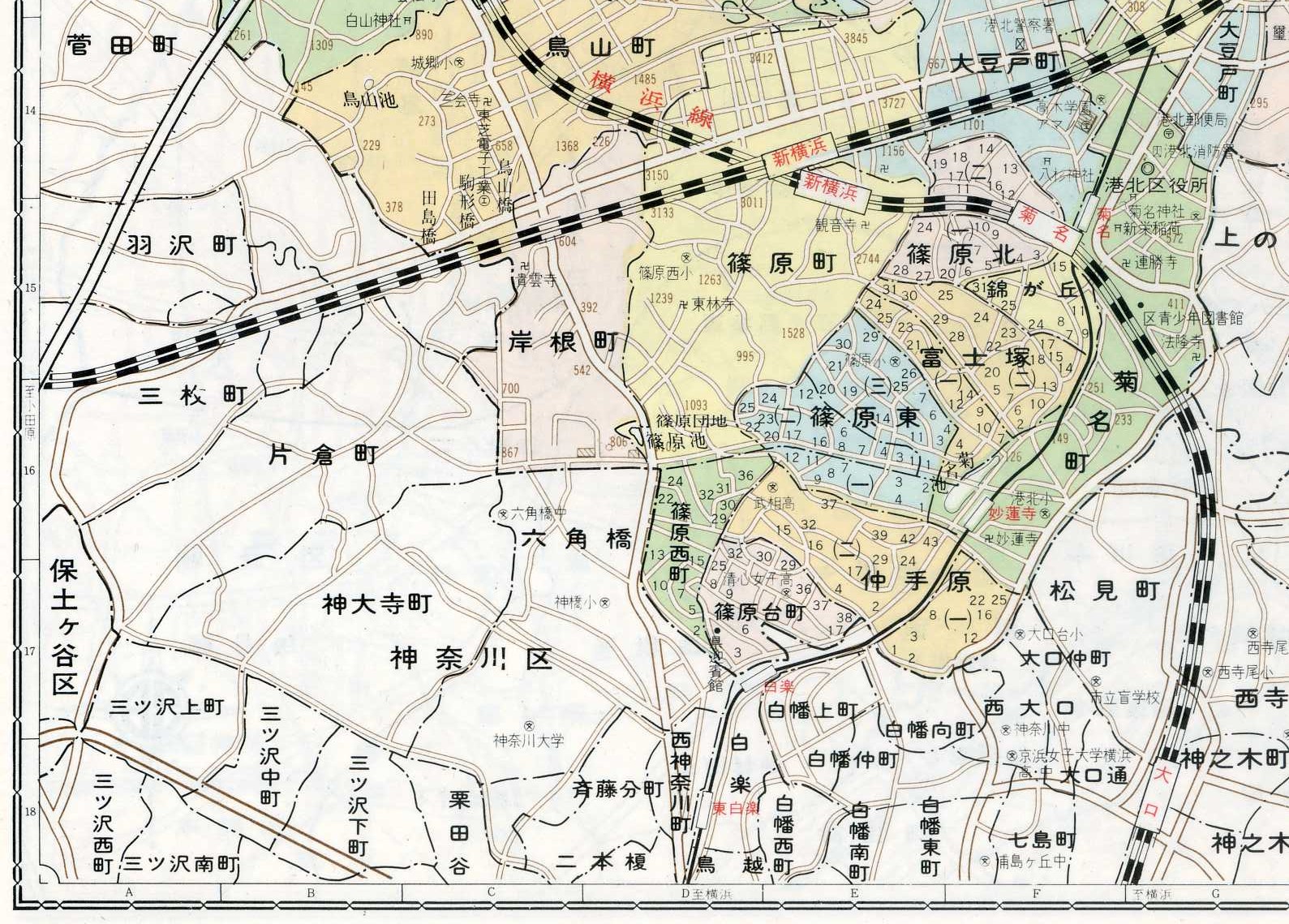

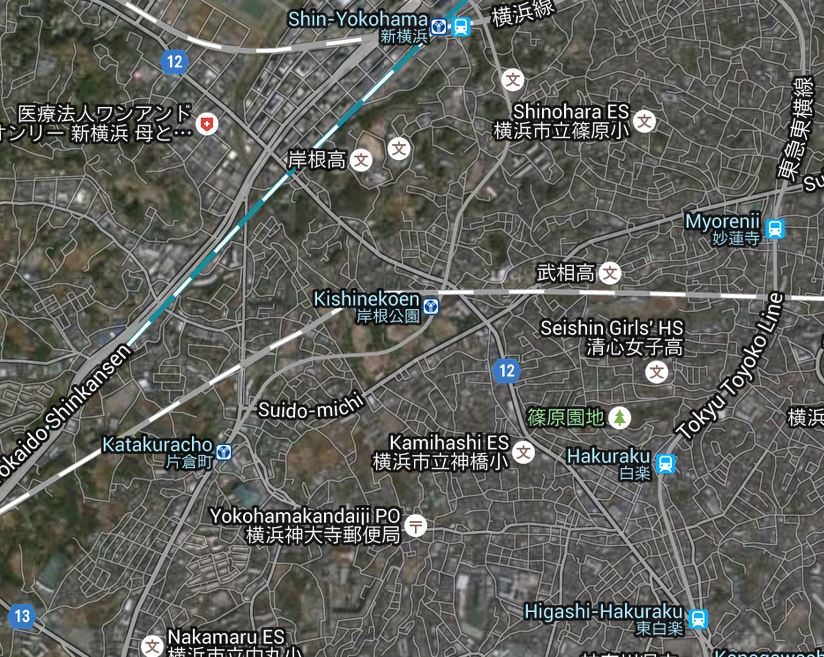

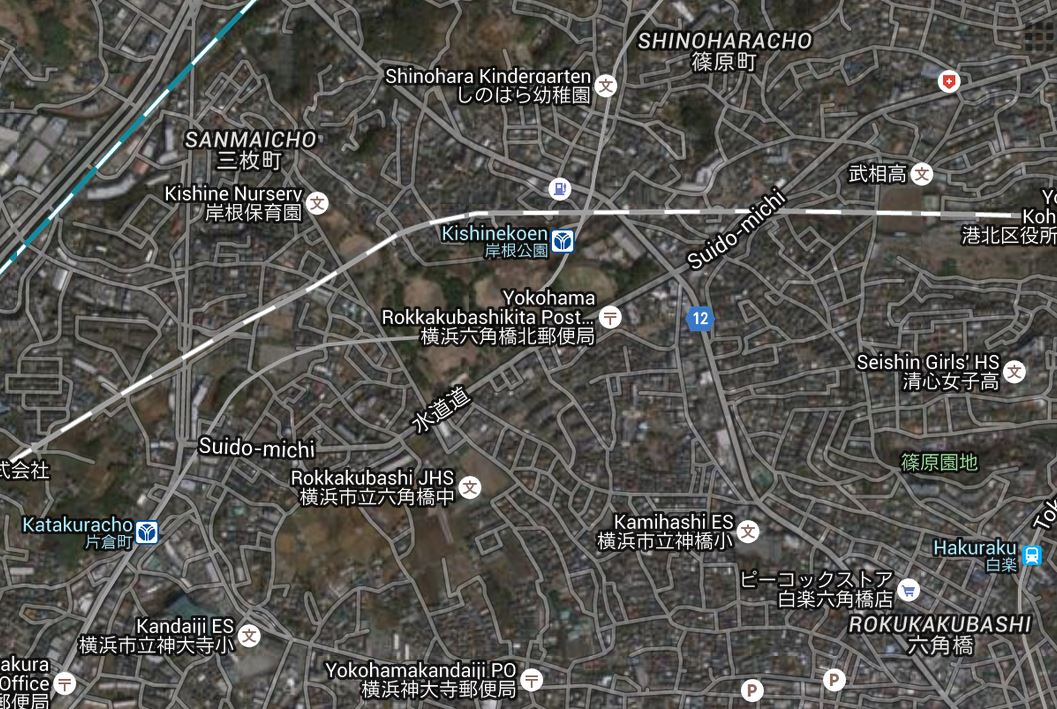

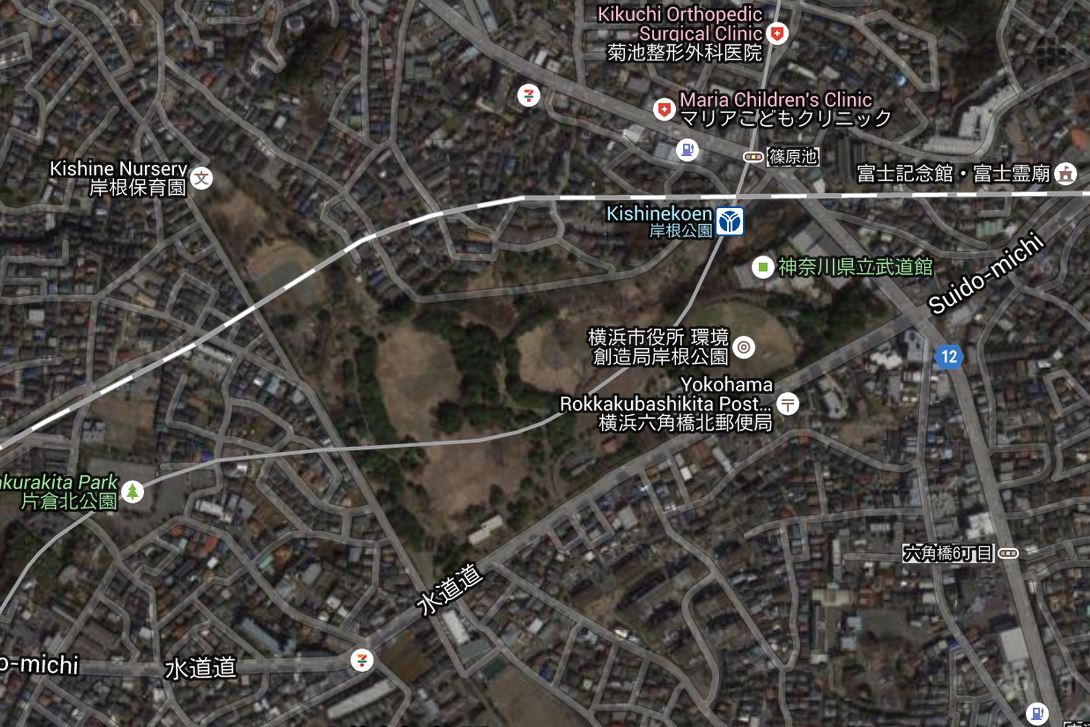

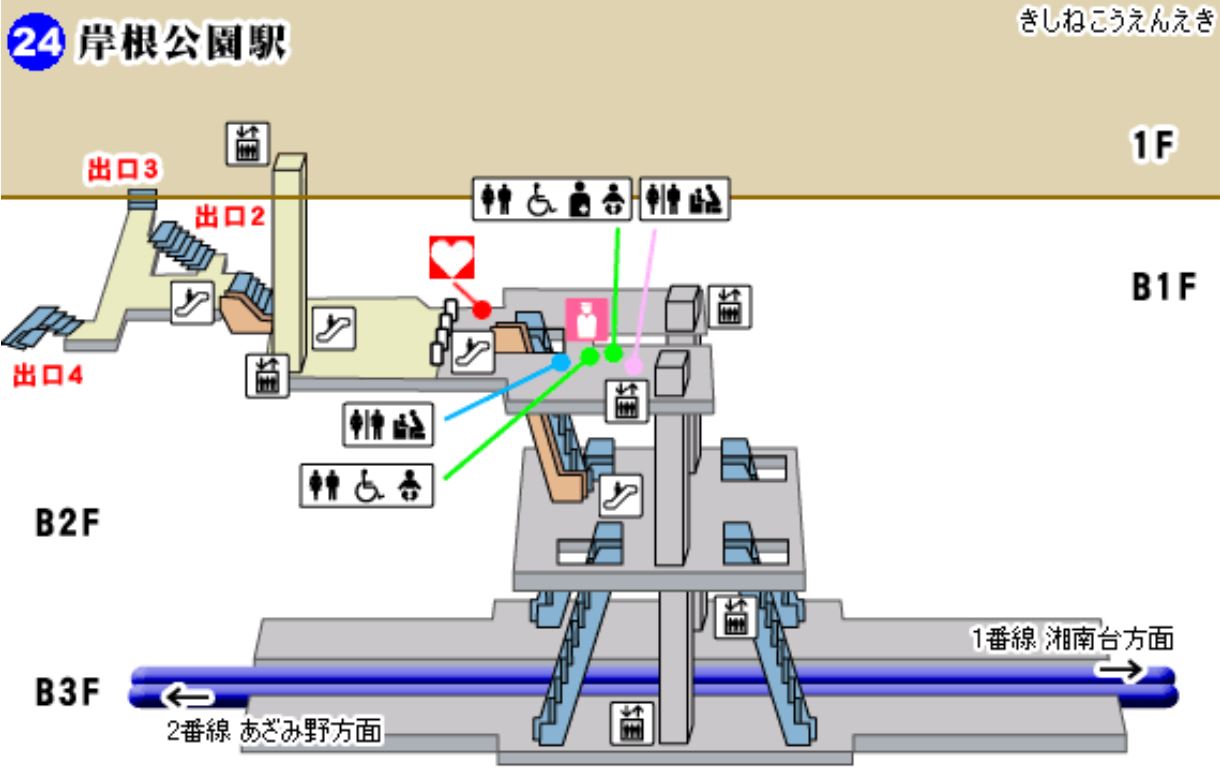

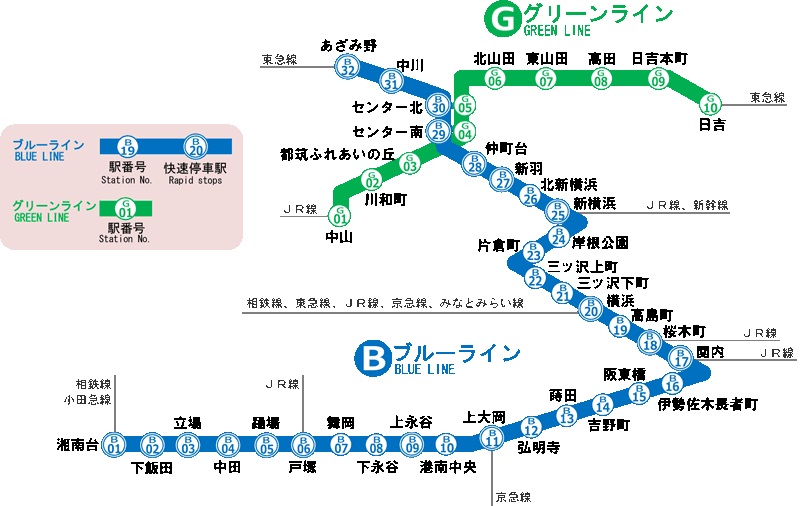

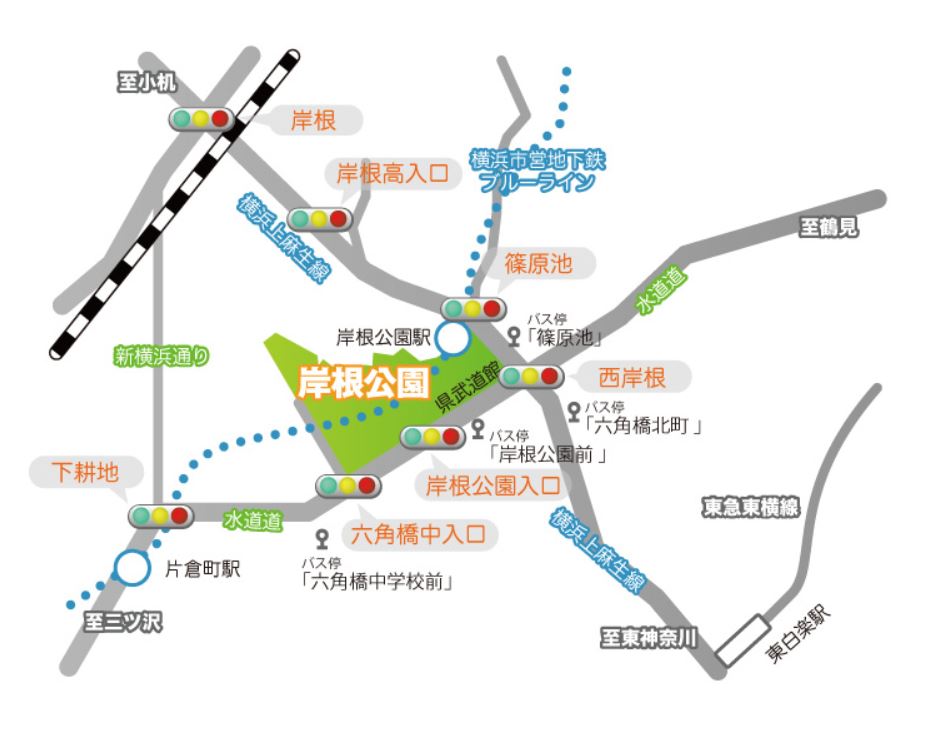

The description of the LOCATION is a bit odd. Kishine Barracks was in Yokohama -- in Kōhoku ward in the northern part of the city. The "Yokohama" that is said to be 4 miles south of Kishine refers to the older part of Yokohama along the central part of the waterfront. The "Tokyo" that is said to be 17 miles north of Kishine refers to the nearest border of Tokyo prefecture. The heart of the city is considerably farther. National Routes 1 and 16 do not extend along any portion of the Kishine area. They pass through the far-flung general area around Kishine and intersect with prefectural roads that approach Kishine. The road that climbed the hill in front of the entrance was then and is still commonly known as Suidō-michi (������) [waterway street] or Suidō-dōro (�������H) [waterway road]. The name reflects the history of the road along an old water course. This is the name of the local stretch of what is more formally called Yokohama City Road Route 85 / Tsurumi-station -- Mitsuzawa line (���l�s��v�n����85���ߌ��w�O�c���). The road intersects at the bottom of the hill with a stretch of Kanagawa Prefecture Route 12 (�_�ސ쌧��12��) known as Yokohama Kamiasao Line (���l�㖃����). The intersection is known as Nishi-Kishine (���ݍ������_). |

Mission

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL

MISSION STATEMENT

1. To maintain and operate 1000 hospital beds for definitive inpatient treatment, to include medical and surgical care in support of military personnel evacuated from SEA and local Army personnel assigned to Kishine Barracks and North Pier, Yokohama under a 60-day evacuation policy.

2. To provide outpatient medical, surgical, and dental care for authorized personnel assigned to North Pier, Yokohama and Kishine Barracks.

3. To operate an intermediate burn center.

4. To provide consultation service covering the various medical and surgical specialties, as requested or directed.

5. To accomplish physical examinations (less flight physicals) for personnel authorized primary medical support.

6. To provide only emergency treatment to authorized dependents. Make such arrangements as necessary to transfer or refer such patients requiring such treatment to the US Army Hospital, Camp Zama or other appropriate militaryPathology (hematology, urinalysis) facilities.

7. To provide medical instruction and training support to USARJ [United States Army Japan] non-medical units in the Yokohama vicinity as requested.

8. To perform the functions of installation commander for the CG [Commanding General], USAMCJ [United States Army Medical Corps] as outlined in USARJ Regulation 10-1.

9. To provide such other medical support as may be directed.

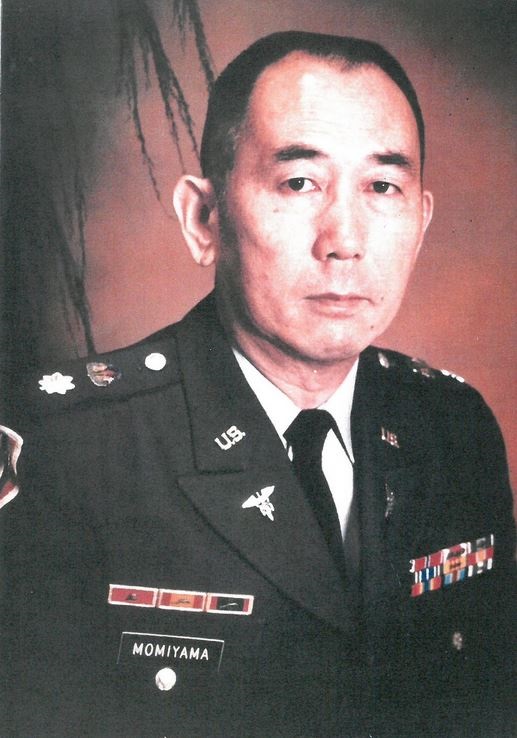

Officers

|

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL KEY PERSONNEL |

||

|

COL Alexander M. Boysen, MC COL Paul A. LaVault, MSC CPT David D. Gibson, MSC COL Harry B. Burkett, MC LTC Raymond J. Bagg Jr., MC MAJ Jerry D. Ballard, MC LTC Helen L. McCormick, ANC LTC James L. Andrews, DC CPT Henri C. Theodore, MC CPT John J. Gisvold, MC CPT Harold Rubin, MSC LTC Joe B. Gipson MAJ William M. Collyer, MSC LTC Lyman Blakesley, MSC MAJ Dorothy Mount, AMSC LTC Hugh J. McKenna, CHC CSM Robert C. Dalehite |

Commandlng Officer Executive Officer Adjutant C, Prof Svc C, Surg Svc C, Med Svc C, Nurs Svc C, Dental Svc C, Path Svc C, Rad Svc C, Pharm Svc C, Pers Div C, Reg Div C, S&S Div C, Food Svc C, Chaplain Command Sergeant Major |

RANKS, CORPS, AND TITLES COL Colonel LTC Lieutenant Colonel MAJ Major CPT Captain CSM Command Sergeant Major MC Medical Corps DC Dental Corps ANC Army Nursing Corps MSC Medical Service Corps AMSC Army Medical Service Corps C Chief |

Organization

|

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL |

||||||

|

COMMANDING OFFICER EXECUTIVE OFFICER |

||||||

|

SPEC STAFF CHAPLAINS |

ADJUTANT | |||||

|

CHIEF PROF SVCS |

CHIEF ADMIN SVCS |

|||||

|

DEPT OF MED SERVICES: General Med Dermatology Gastro Chest & Comm Disease Neurology Psychiatry Cli Psych Social Work Cardiology Hospital Clinic |

DEPT OF SURG

SERVICES: General Surg Opthamo Otolaryn Orthopedic Neurosurgery Thorac Surg Urology Anes & Opr Physical Med |

RADIOLOGY SVC

SECTIONS: Diagnostic |

MGT SVC OFC

BRANCHES: None |

PERSONNEL DIV

BRANCHES: Mil Pers. Medical Co. Med Hold Co. Welfare & Recreation |

REGISTRAR DIV

BRANCHES: A & B Med Records & Reports Hosp Treas. |

|

|

NURSING SVC

SECTIONS: Medical Surgical Hosp Clinic CMS OR Nursing Anes Nursing |

PATHOLOGY SVC

SECTIONS: Anatomical Clinical |

DENTAL SVC

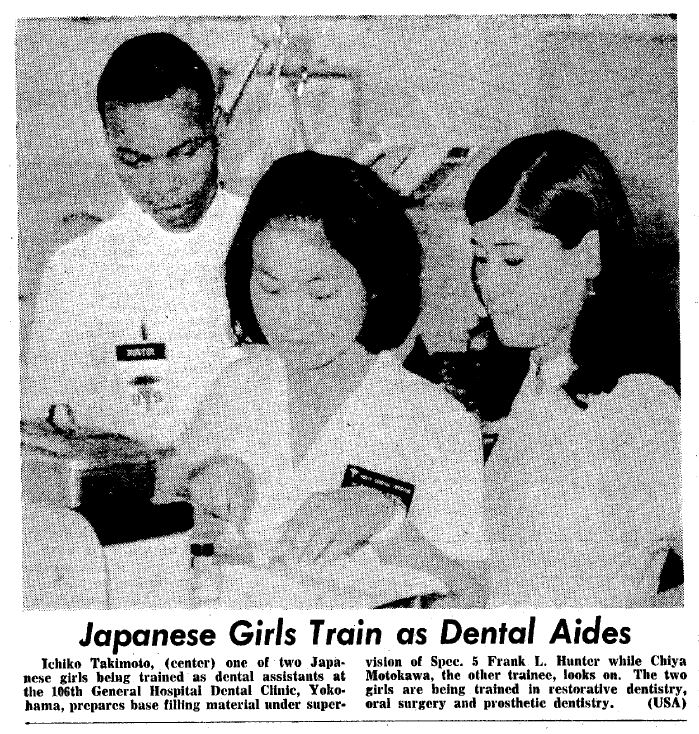

SECTIONS: Oral Dg Periodontia Restorative Dentistry Oral Surgery Prosthodontia |

SUP & SVC DIV

BRANCHES: Property Mgt Service Supply |

PLAN & Tng Div

BRANCHES: Plans Training |

FOOD SVC DIV

Diet Therapy Production & Service |

|

|

PHARMACY SVC

SECTIONS: Dispensing Manufacturing |

||||||

Operation

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL

OPERATIONAL DATA

THROUGH 31 Dec 68

AVERAGE DAILY BASIS

Everyday during the past year the 106th General Hospital has:

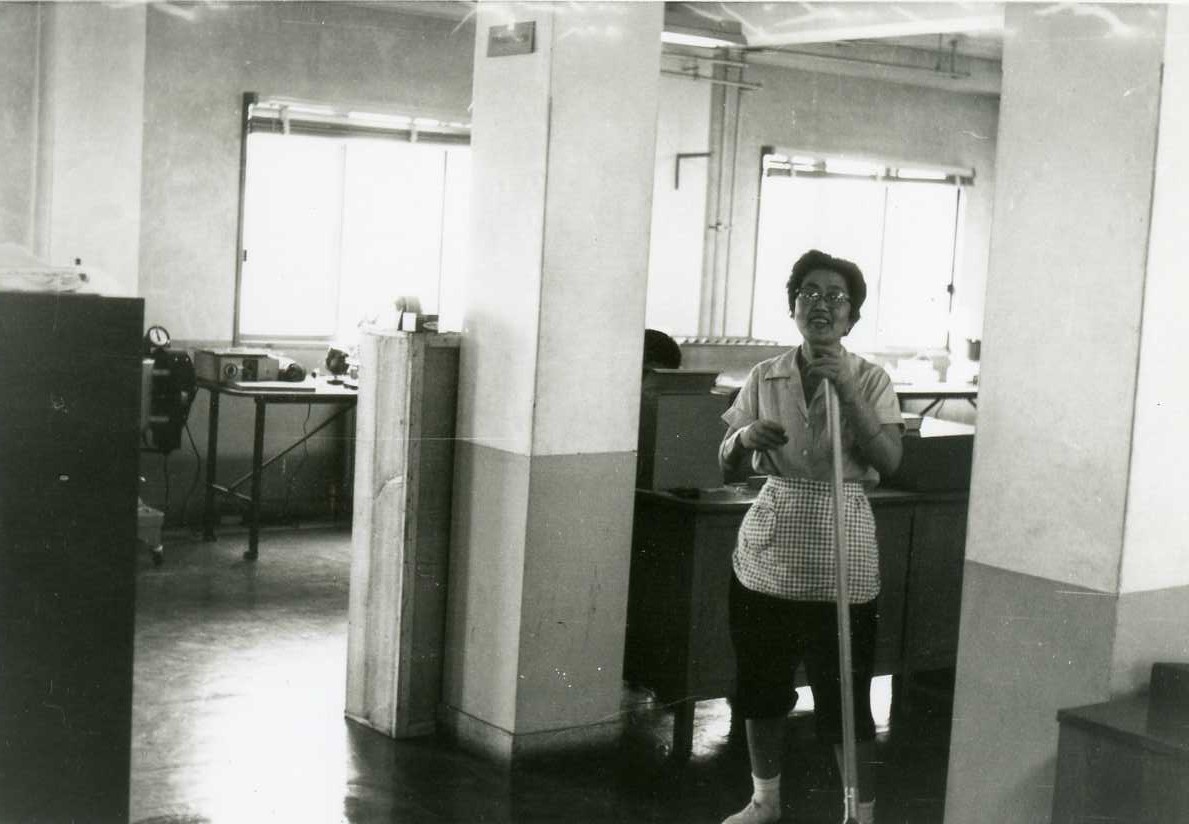

Admitted 37 patients from Vietnam of which 30 were surgical cases and 7 were medical. 23 of these patients were injured as a result of hostile action. Each patient was hospitalized 21.9 days. The hospital discharged 37 patients of which 28 were Army and 9 were Navy/Marine. 29 of these patients were transferred to CONUS [Continental United States] hospitals and 8 were returned to duty. In treating these patients, 30 Operating Room procedures were performed, 258 X-rays were taken, 2014 Lab procedures were performed, and 33 units of blood were prepared. The Dental Clinic treated 44 patients, and the mess hall served 2261 meals. 4487 pieces of mail were delivered and 38 personnel records were received and processed. $2335.00 was sent [sic = spent] on consumable medical supplies and $604.00 was invested in medical equipment. In providing this service 5395 permanent party man-hours were expended.

I found this especially interesting. I would never have thought of comparing the number of lab procedures performed every day to the number of meals the mess hall served. Judging from the variety and volume of work that was done at the pathology lab when I was there in 1966, I would guess that most of the lab procedures in 1968 were also related to blood work. A request to draw blood would typically call for several procedures -- from routine blood cell counts, and differentials and hematocrits, to one or more specific blood chemistry tests. The number of meals served seems low -- considering that the report says the operating strength was 649 military personnel and 258 civilians, and an undisclosed average number of patients on any given day. Presumably the civilians packed their own lunches. But surely the patients, and most of the military personnel, ate on base, and I would think they most likely ate food prepared by the mess hall.

Hospitalization

|

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL LENGTH OF HOSPITALIZATION, SELECTED CASES 1 Jan - 31 Oct 68 |

||||||

| DIAGNOSIS |

PATIENTS |

AVERAGE LENGTH OF STAY |

TOTAL DAYS LOST |

ABBREVIATIONS |

||

|

MAJ AMP (Lower Extrem) Fx Femur Fx Tibia Thoracic Wds ABD Wds W/Gu Involvement ABD Wds W/Colostomy ABD Wds W/Liver Inj Craniotomy Malaria Hepatitis Psychiatry Maj Vascular Inj Maj Burns Maxillo-Facial Inj Totals |

365 252 377 416 193 222 147 201 214 221 304 112 298 129 3,451 |

12.76 32.50 19.02 15.21 15.34 15.52 13.88 12.37 21.70 26.94 21.09 16.85 8.69 20.81 18.12 |

4656 8189 7169 6326 2961 3546 2040 2487 5643 5953 6411 1887 2591 2685 62,544 |

|

||

Labor costs: Consumables but not expendablesThe red figures are mine. I calculate an overall average of 18.12 "days lost" per patient (65,544 total days lost / 3,451 total patients). At face value this would seem to mean about 2.5 weeks of hospitalization per patient. The "days lost" metaphor suggests that Army statisticians view soldiers as employees who provide labor in return for pay -- which, in a sense, they are. What is not reflected in such figures is the "days lost" in the name of the labor required to evacuate and care for the sick, injured, and wounded. Presumably this cost is higher than the average per-capita cost of maintaining an average soldier in the war zone. The costs of providing the long-term, even life-long care that the seriously injured and wounded have require is of course another "cost factor" that government bean counters and fund allocators have to consider. Soldiers and veterans may still be "consumables" but they are no longer "expendables". The more serious the conditions, the shorter the stayNotice that the hospitalizations of malaria, hepatitis, and psychiatry patients -- all medical rather than surgical admissions -- are longer than all of the surgical conditions except fractured femurs. Patients that presented more difficult conditions, that would require longer periods of convalescence and rehabilitation, tended to have the shortest hospitalizations at Kishine. |

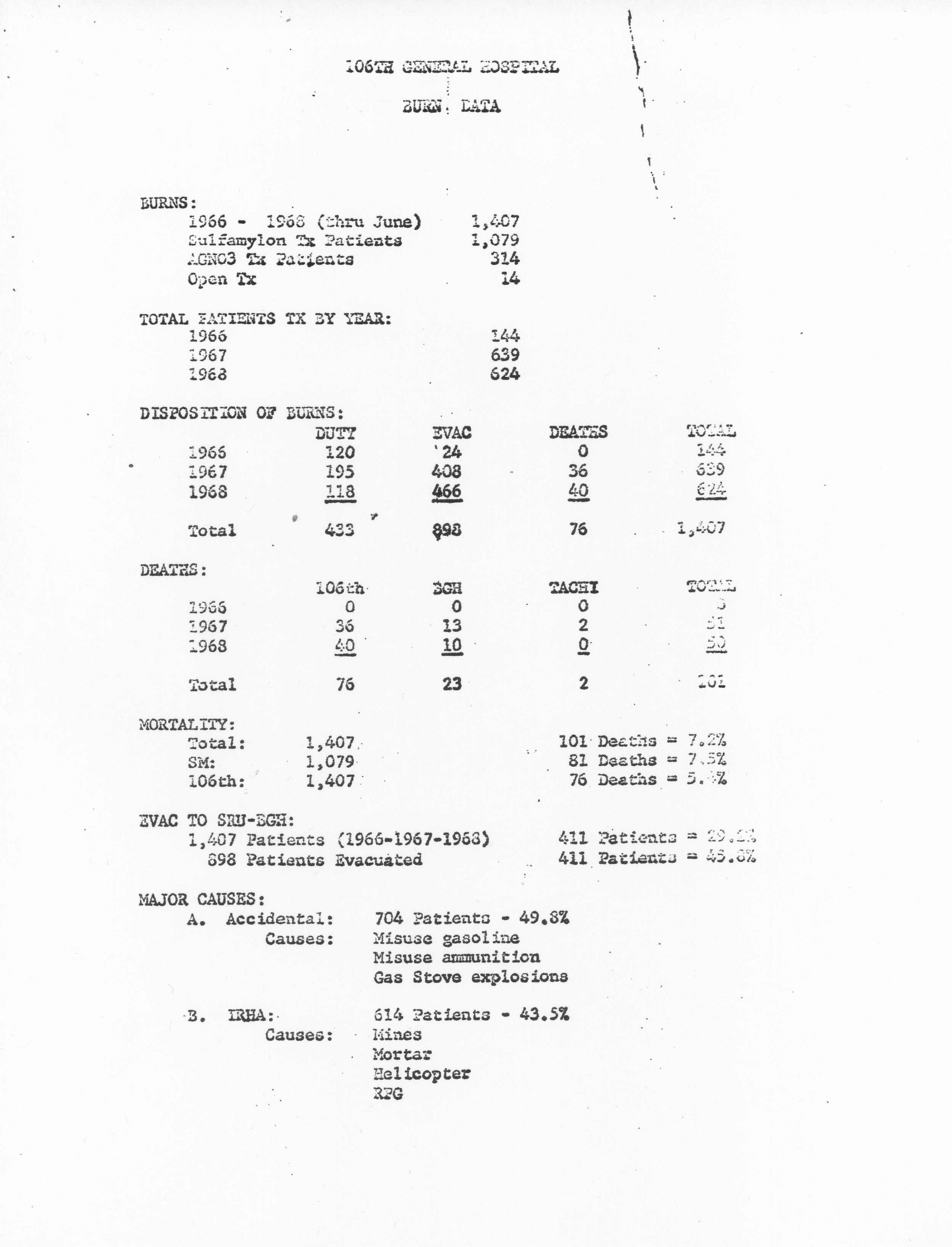

Burns

106th General Hospital burn statistics

106th General Hospital burn statistics1966, 1967, and 1968 through June Page 8 of 1969 report as scanned |

|

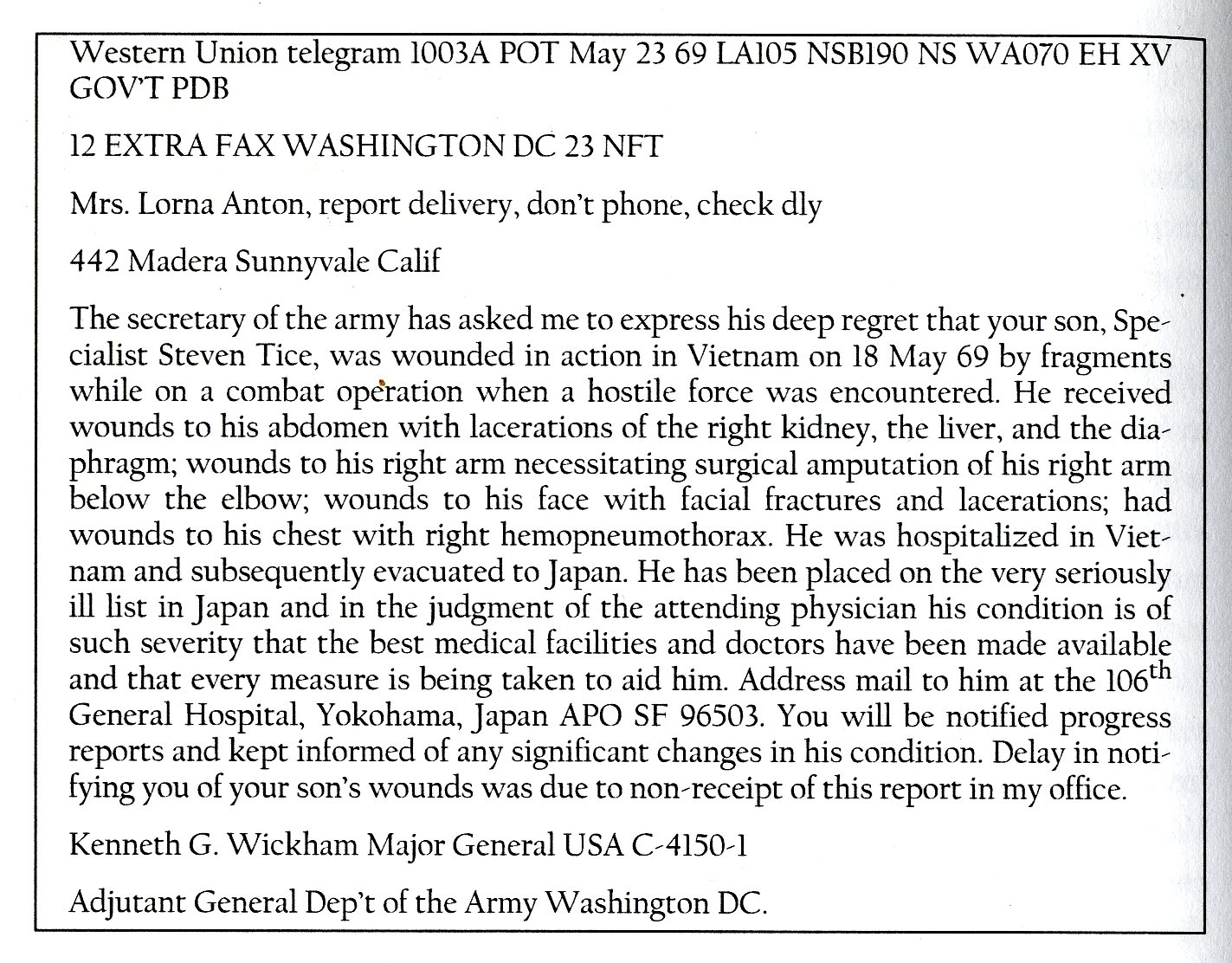

Treatment �� "Tx" means "treatment". At the time, the two most common approaches to controlling infections in open burns were silver nitrate (AGNO3), a more traditional treatment, and sulfamylon (mafenide acetate), which had been more recently introduced. Both were topically applied in various ways -- silver nitrate in the form of soaks, in which gauze soaked with silver nitrate was placed directly on an exposed burn -- and sulfamylon in the form of an antimicrobial cream. "Open Tx" was just that -- leaving the burn exposed with no topical treatment. Disposition �� More burn patients were evacuated from the 106th to facilities in the United States than were returned to duty. Deaths �� 101 of the 106th's 1,407 major burn patients died -- 76 at the 106th, 23 at Brooke General Hospital (BGH) at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, and 2 at Tachikawa Airbase presumably en route to BGH. Evacuation �� 411 or 29.2 percent of the 106th's 1,407 major burn patients were evacuated to the Surgical Research Unit (SRU) at Brooke Army Hospital (BGH), which amounted to 49.8 percent of all patients evacuated from the 106th. The Surgical Research Unit (SRU) at Brooke General Hospital (BGH) treated patients with infected burns and other wounds on a special ward. This evolved into today's U.S. Army Burn Center at the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research at Brooke Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston (L.C. Cancio and S.E. Wolf, "A History of Burn Care", in Marc G. Jeschke et al., editors, Handbook of Burns: Volume 1: Acute Burn Care, New York: Springer-Wien, 2012, page 8). Causes �� That more major burns in Vietnam were caused by accidents than by "injury resulting from hostile action" (IRHA) has often been cited as an example of the tragedy of war zone injuries that could have been prevented. See other reports (below). Among the causes of IRHAs, "RPG" refers to "rocket-propelled grenades". |

|

U.S. Army reports on medical support in Vietnam made the following observations about the role of the 106th General Hospital concerning "secondary care" for surgery patients, especially those that required orthopedic surgery, and "burns" [bracketed remarks mine].

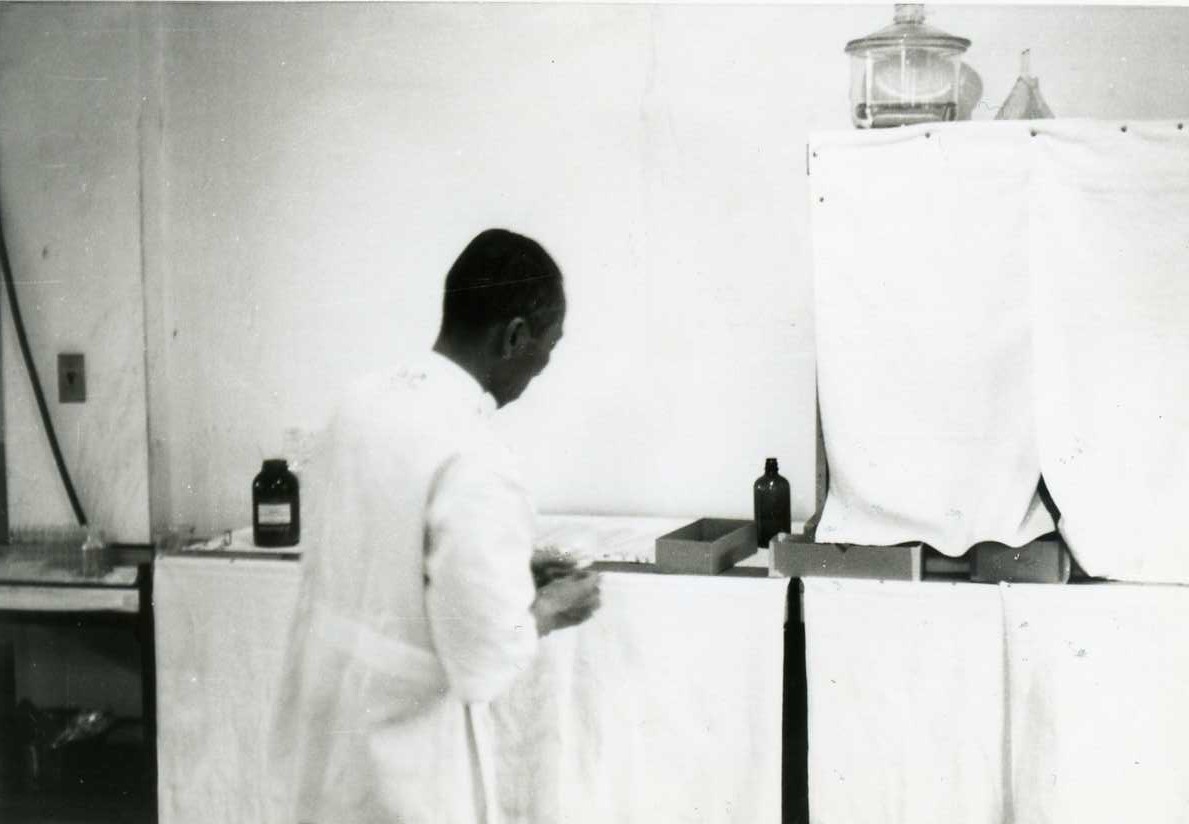

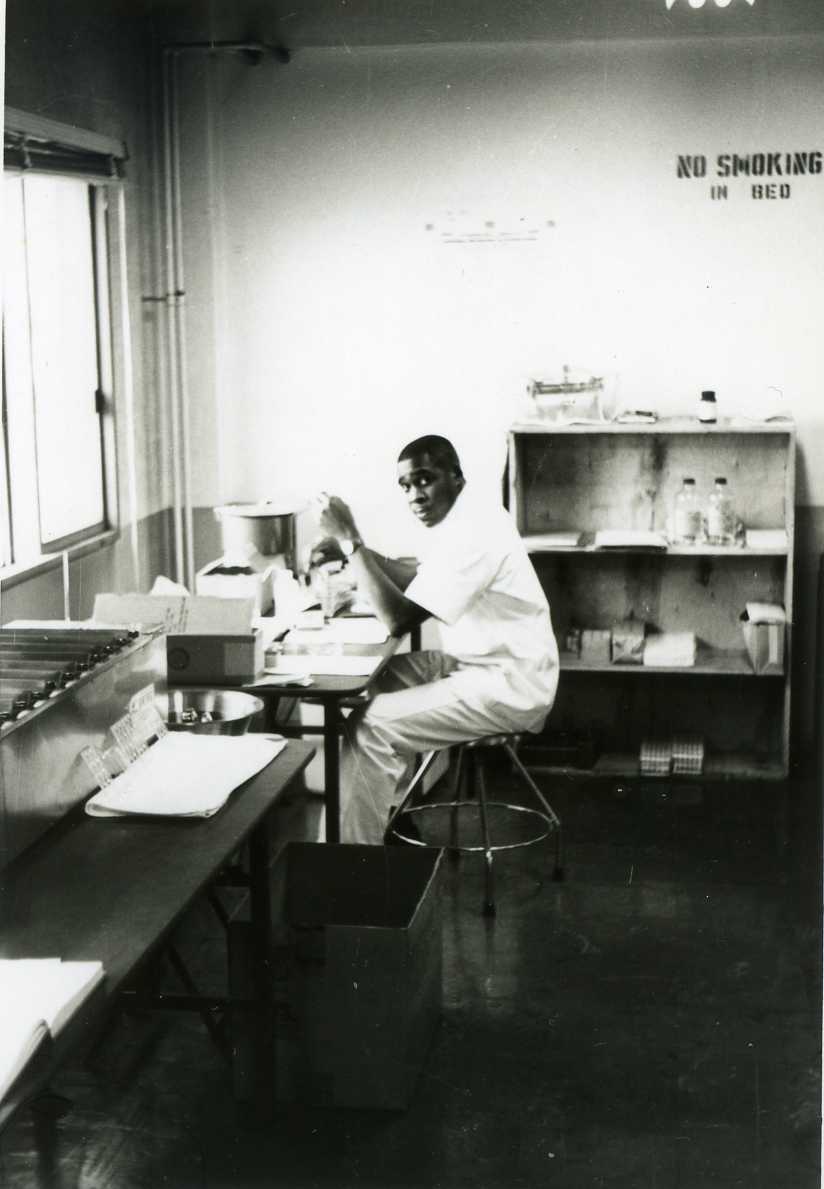

|

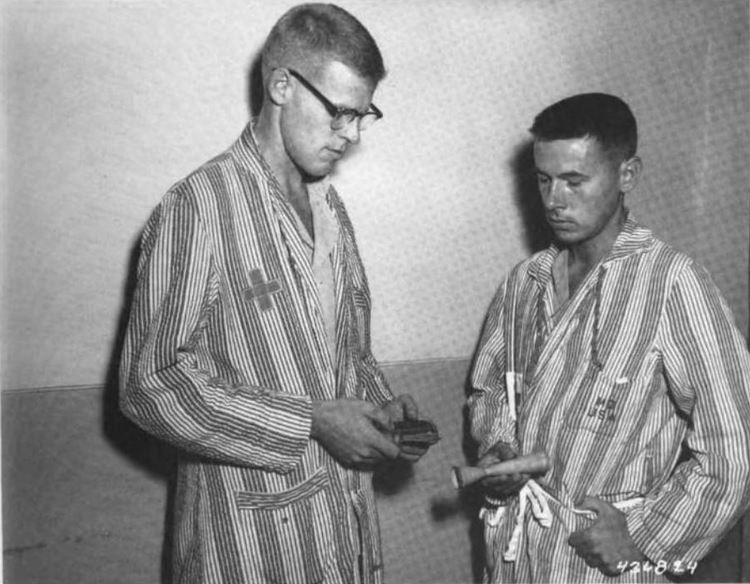

Confessions of a vampire on the burn wardThough I ended up working mainly in the microbiology (bacteriology and parasitology) section of the lab, I did my share of rounds drawing blood, on all wards, including the burn ward. When I was at the 106th in 1966, the burn ward -- as I recall -- was on the 2nd floor of Building C, just a few steps across the way from the lab, which occupied the small building between B and C after provisionally setting up in Building B. Every ward presented different challenges in terms of the types of patients. All patients were the same, though, when it came to the first rule of drawing blood -- to make the patient feel at ease, especially if we were meeting for the first time. Second and subsequent draws were easier if the first draw left the patient feeling that I could be trusted to do relatively painless work. What's different about burn patients is, of course, the burns -- "thermal injuries" to body tissue caused by heat or chemicals. I'm not talking about the minor burns you get touching a hot kettle, spilling boiling water, or getting a sleeve too close to a flame. I'm talking about burns caused by explosives, ignited fuels and chemicals, the kind you get from incendiary weapons, white phosphorus munitions, napalm, gasoline, jet fuel -- major burns that cover substantial parts of your body, all the worse if they also involve your head and face. Before I could begin to try to make a patient feel at ease with a stranger wielding a needle, though, I had to make myself feel at ease with the patient. After the 106th began operating, I quickly enough got used to the commonality of the mangled bodies that occupied many of its beds. The sights were very different from those I'd seen in the surgery and recovery wards of the hospitals where I'd worked in the United States. While located in the peaceful suburbs of a country that was several thousand miles from Vietnam, the 106th was nonetheless a battlefield hospital. The most difficult challenge for me, at Kishine, was to tame my natural curiosity about not only a patient's medical condition, but the conditions that caused the injuries or wounds -- in this case the burns. If the patient volunteered to tell his story, fine. If not, then I would hesitate to ask unless I saw signs that the patient might actually like to talk about what happened. Some patients did, and some didn't, voluntarily related what had happened to them. At times a ward nurse or corpsman would intercept me and alert me as to which patients were having emotional difficulties on top of their physical injuries. These included patients who had been involved in severe combat and were unable to get any information about other men in their unit -- how their wounded buddis were doing, who had been killed. These also included patients who, in addition to their extreme pain and discomfort, were dwelling on certain or probable prospects of lifelong disfigurement. I hated saying things like "How are we doing today?" to patients who were obviously miserable. I was more apt to say something like "You don't look like you're having fun" -- in a way that would be taken as a sincere acknowledgement of the patient's difficulties. I was generally good at what I did, but some patients were tired of being pin cushions. Some had experienced failed attempts by others -- a lab tech, corpsman, nurse, or doctor -- who were having a bad day or were careless or unskilled. But no matter how much confidence I had in my own abilities and tried not to show occasional doubts, there were times when I couldn't guarantee that it wouldn't hurt -- or that I wouldn't bungle an attempt to hit a vein. There's a saying in Japanese -- "Even monkeys fall from trees" (Saru mo ki kara ochiru �������痎����) -- and yours truly considers himself just another monkey. Bananas happen to be -- I'm not kidding -- the Wetherall "family fruit". The point is, though, I always went into a vein with an awareness of a small but real probability of failure. I was supposed to remain calm and give the patient the impression I knew what I was doing. But sometimes I'd joke about it. "Don't worry. I'm as nervous as you are." And take it from there. It could go in all manner of directions. Some patients called phlebotomists vampires. "I've got to draw some more blood." "Is it that good?" "Some post-op tests and another blood culture. I hear your surgery went well." "They gave me some blood. And now you want to take it back." "From the blood bank, right? "Right." "You can keep the blood, but you gotta pay interest." Most vampire jokes are of the kind you can tell your mother and not get your mouth washed out with soap. Two blood cells loved in vein. A red cell asks another for a date, and the other says, "Sorry, you're not my type." A psychiatrist tells a B- blood cell suffering from depression to be more positive. Artistic vampires are good at drawing blood. Vampires go fishing in the blood stream. Sometimes I did have to fish for a vein, or fish around inside one. The arms of some patients were so badly injured that I couldn't draw blood from a conventional vein. Or the conventional veins were intact but had collapsed from excessive punctures. An alternate site might be indicated on the patient's chart. Or a nurse might bring such a site to my attention. If I didn't immediately spot a suitable vein, I'd look for one. I might ask, "Where have they been drawing your blood?" Or I might look at a bunch of puncture marks and joke, "Do you have any good veins left?" -- while meeting the patient's eyes, which invariably would be watching me, most likely with considerable anxiety. When I found a possible site, I'd prepare the needle and tubes, while talking to the patient about anything other than something I thought might upset him. I resorted to light humor if possible. But some patients were in no mood for levity. Or they were burned or otherwise injured in such ways that made smiling or laughing painful or even impossible. Drawing from veins that could not clearly be seen or palpitated increased the likelihood of failure. Obesity increased the likelihood of having to go for a vein I suspected (or hoped) was there but couldn't actual feel. Unlike some of the patients I had drawn at stateside Army hospitals, which also treat dependants, patients from Vietnam were rarely fat. Even with lean patients, however, some sticks are harder than others. I sometimes sought advice, and was always prepared to admit defeat, but I never encountered a patient whose peripheral blood I couldn't somehow draw. At times I had to draw from a vein on the back of a hand, or leg, ankle, or foot. Such draws can be painful even for the person wielding the needle, who vicariously experiences being in the patient's skin. If no one is able to draw blood using conventional methods of venipuncture, then a doctor has to perform a venous cutdown. I have never witnessed one. As much as I sometimes wanted to, there wasn't a lot of time to linger and talk with patients. When especially busy, I had no choice but to minimize conversation. And even when there was time to talk, there were times when I concluded that the kindest I could be to a patient was to go about my work in silence. |

Personnel

|

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL PERSONNEL DATA 9 January 1969 |

||||

| CATAGORY | AUTH STRENGTH |

OPERATING STRENGTH |

ABBREVIATIONS | |

| OFFICERS | ||||

|

MC DC MSC AMSC ANC CHC WO TOTAL OFFICERS TOTAL E.M. TOTAL MILITARY |

42 4 18 11 92 3 1 171 405 576 |

43 4 19 12 85 3 1 167 482 649 |

MC DC MSC AMSC ANC CHC WO EM |

Medical Corps Dental Corps Medical Service Corps Army Medical Service Corps Army Nursing Corps Chaplain Corps Warrant Officer Enlisted Men |

| CIVILIAN | ||||

|

RN (Part Time) JN DAC TOTAL CIVILIAN |

12 268 12 292 |

10 239 10 259 |

RN JN DAC |

Registered Nurse Japanese National Department of the Army Civilian |

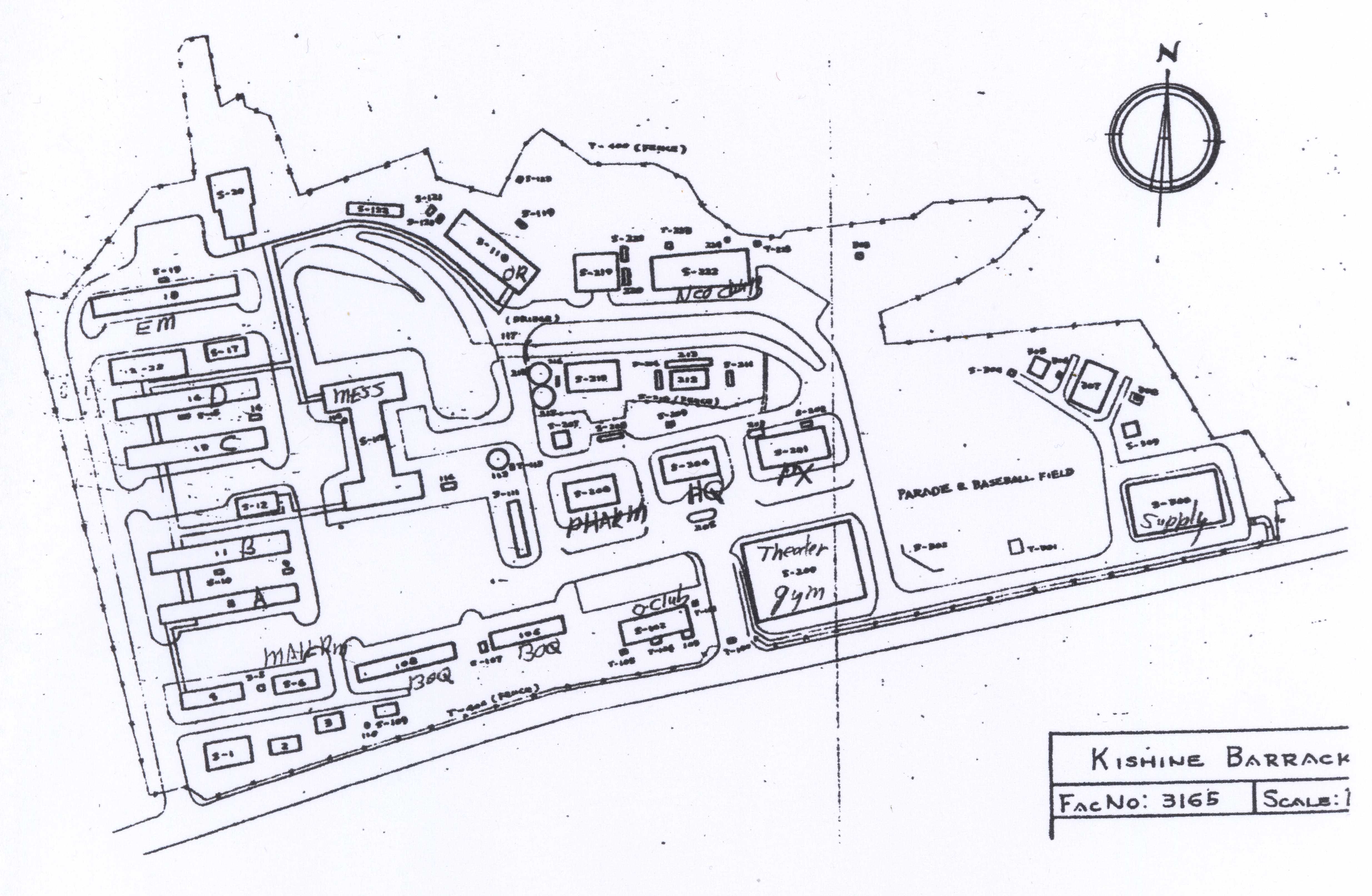

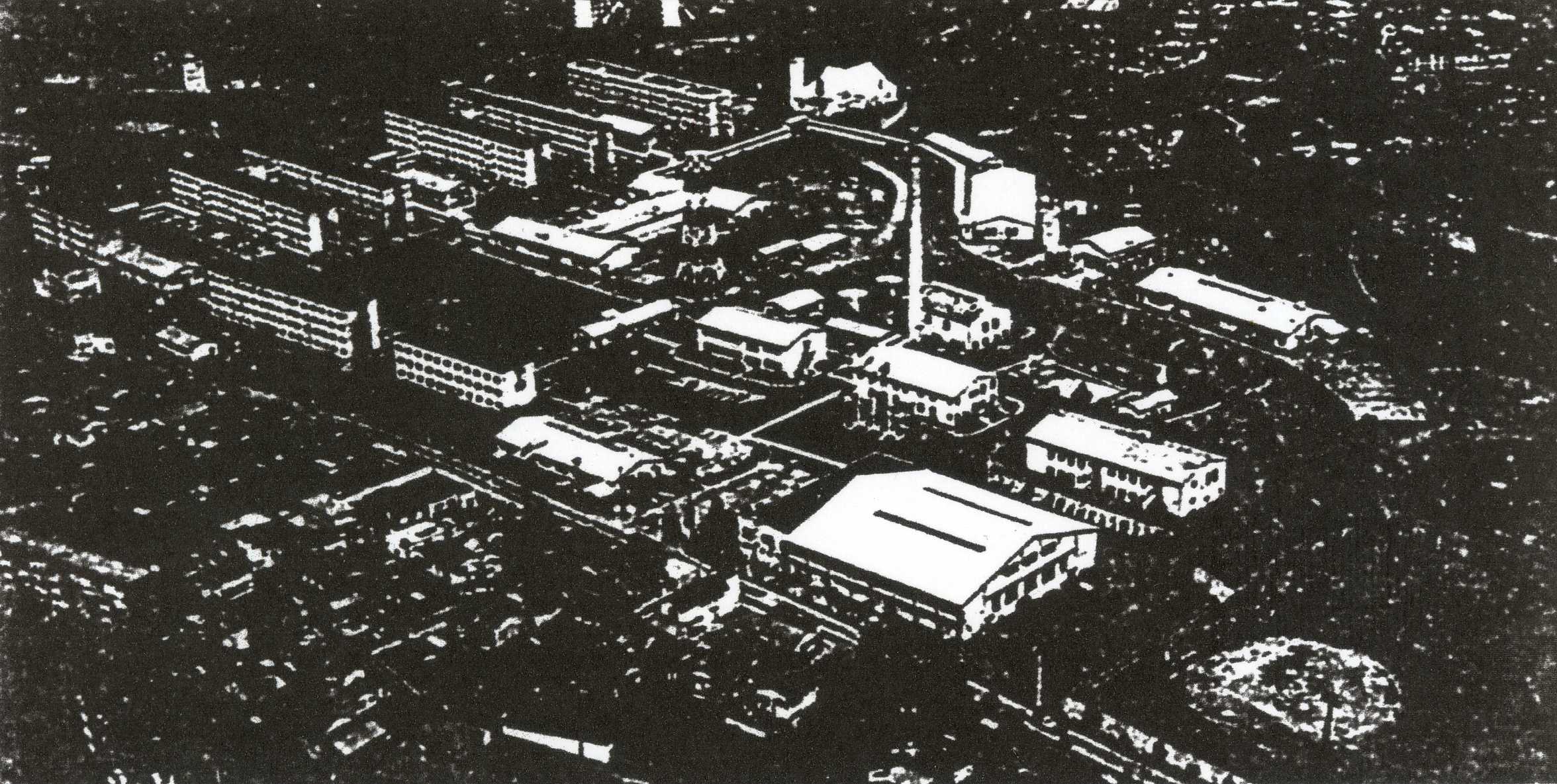

Map

Click image to enlarge

Click image to enlargeMap of 106th General Hospital installations Page 10 of 1969 report as scanned |

The numbers of the buildings on the above map are explained in key on the following page. The numbers are difficult to read but some can be better made out by enlarging the image. The scan is 600dpi -- the highest definition that was meaningful. The handwritten information is as marked on the received map.

Buildings

|

106TH GENERAL HOSPITAL INSTALLATION MAP KEY TO MAJOR BUILDINGS |

|||

| BUILDING NUMBER |

CONTENTS |

ABBREVIATIONS |

|

|

4 S-6 8 11 S-12 13 16 S-17 18 S-20 S-23 S-102 106 108 S-111 S-115 S-118 S-122 S-200 S-201 S-204 S-206 S-207 S-208 212 S-215 S-219 S-222 S-300 303 307 |

Registrar and BEQ Mail Room, APO, Linnen Exchange, and Unit Supply "A" Wards "B" Wards Pathology "C" Wards "D" Wards Radiology Enlisted Billets Chapel Baggage Room Officer's Club [sic = Officers Club] BOQ BOQ Dental Clinic Mess Hall Operating Room and Recovery Room Central Material Supply Theater and Gymnasium Post Exchange, Snack Bar, Barber, Tailor and Bowling Alley Headquarters, Personnel, Finance Hospital Clinic, Pharmacy, Medical Library, EENT Clinic, and Education Center Telephone Exchange Local National Dispensary and Snack Bar Swimming Pool Power Plant Fire Station and Security Guard NCO Club Supply and Service Ammunition Bunker Sewage Plant |

BEQ APO BOQ EENT NCO EM OR HQ PX |

Bachelor Enlisted Men's Quarters Army Post Office Bachelor Officer [Officers] Quarters Eye(s), Ear(s), Nose, and Throat Non-Commissioned Officers Enlisted Men Operating Room(s) Headquarters Post Exchange |

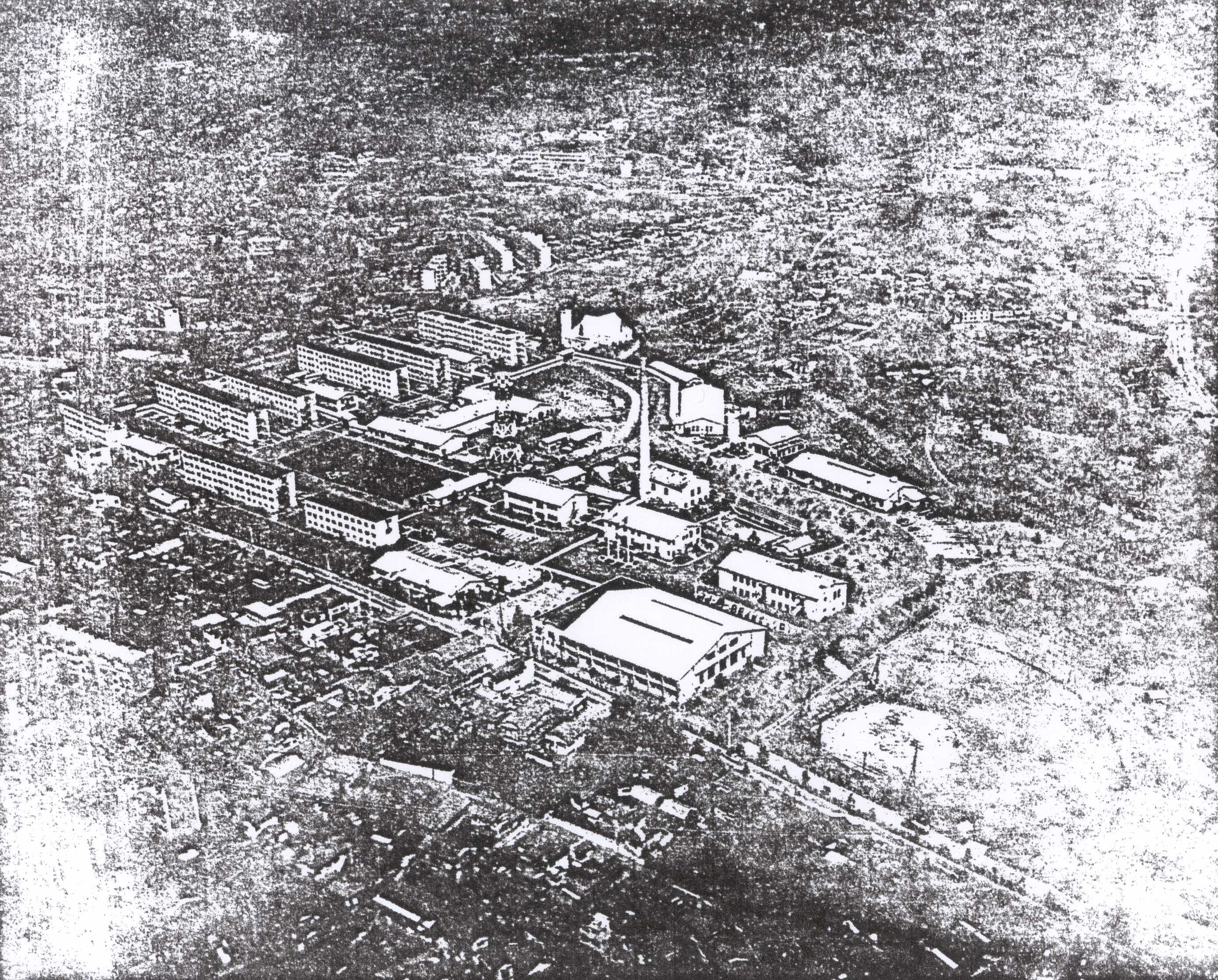

Photographs

|

|

|

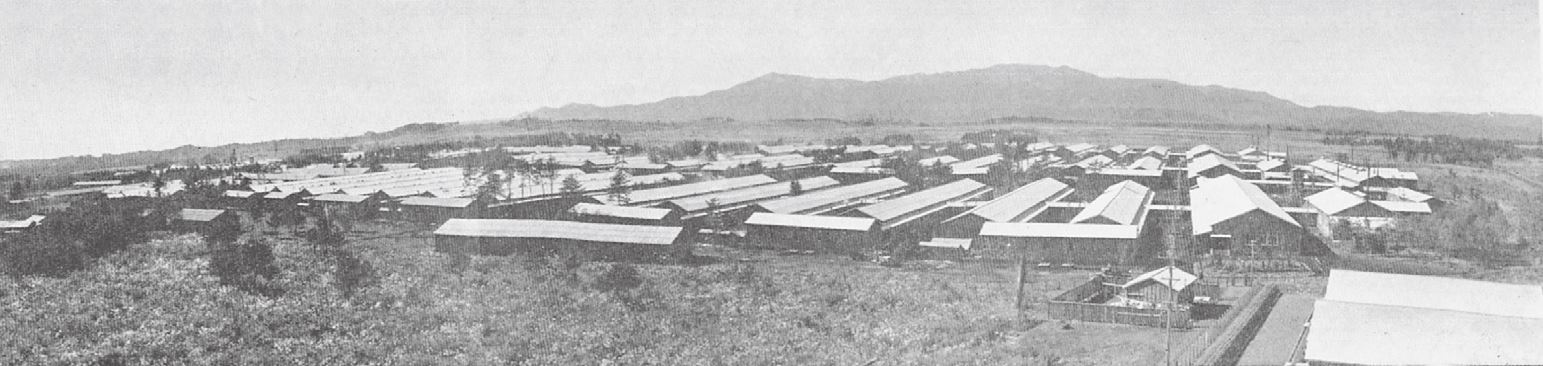

|

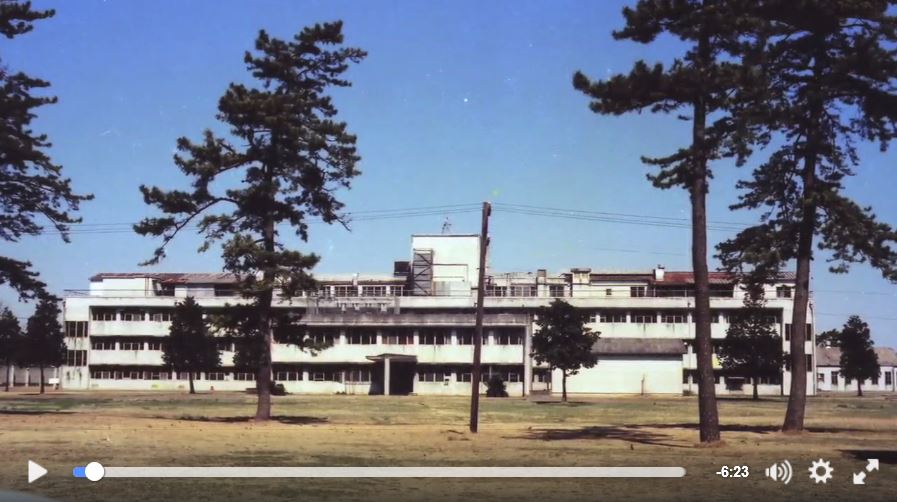

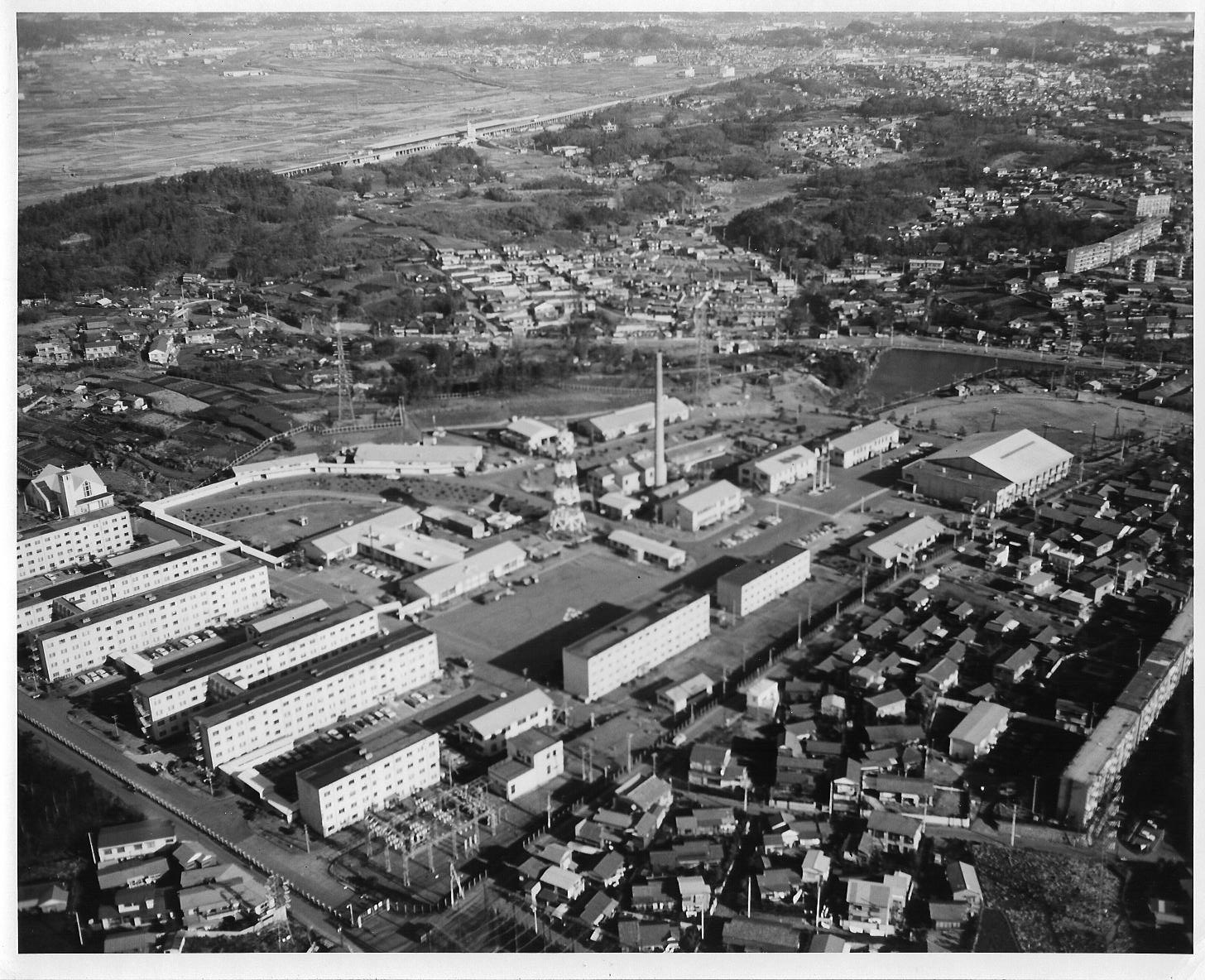

Click on images to enlarge Aerial views of Kishine Barracks from southeast Scans from copies of pages 12 and 13 of 1969 report as received. Dates and photographers unknown. Probably around 1968. Compare with similar photgraph to right. |

Click on image to enlarge Aerial view of Kishine Barracks from southeast Date and photographer unknown. Probably around 1967. The water tower has been painted white and red. See Tenney (1967) for details. |

|

The black-and-white photographs on the left came at the end of the received 1969 report on the 106th General Hospital. The darker second photo to the right appears to be a crop from the first photo. The baseball field is in the lower right corner. The large building to its left is the theater and gymnasium. The entrance gate is just to their left, and just to its right is the Officers Club. The white building top and center is the chapel.

The color photograph to the right was taken from almost the same aspect as the black-and-white photograph but a bit further to the west (left), which made the tower and chimney appear more to the east (right) of the view. See Tenney (1967) below for story that this picture was attached to by a soldier who was evacuated to the hosptial from Vietnam.

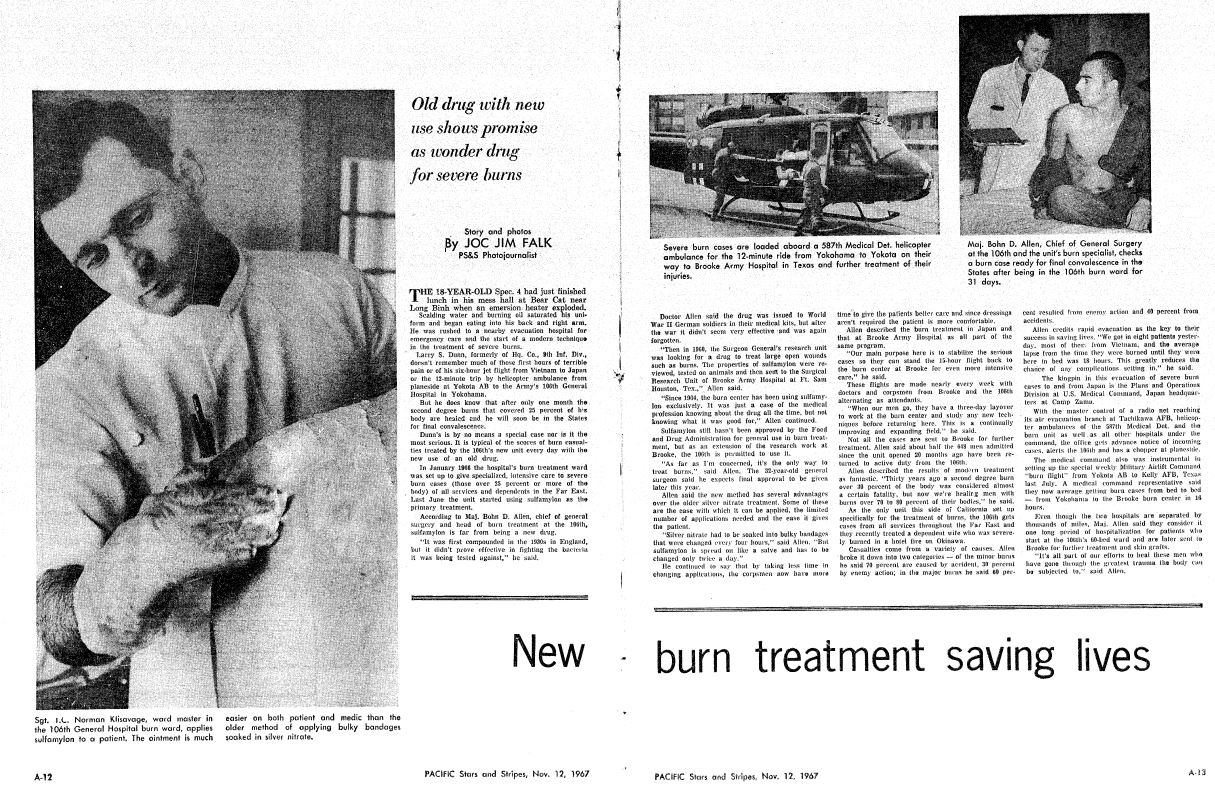

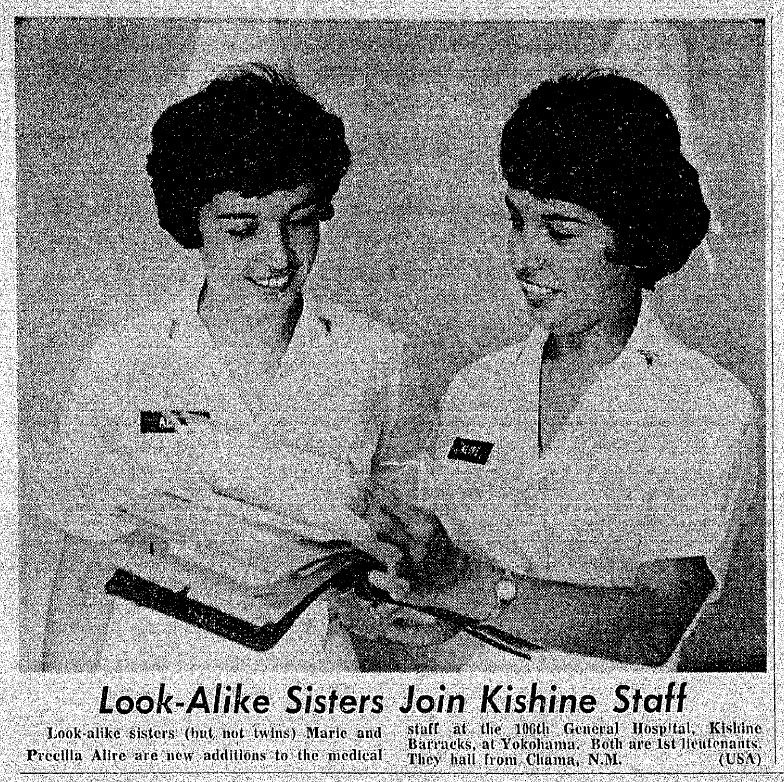

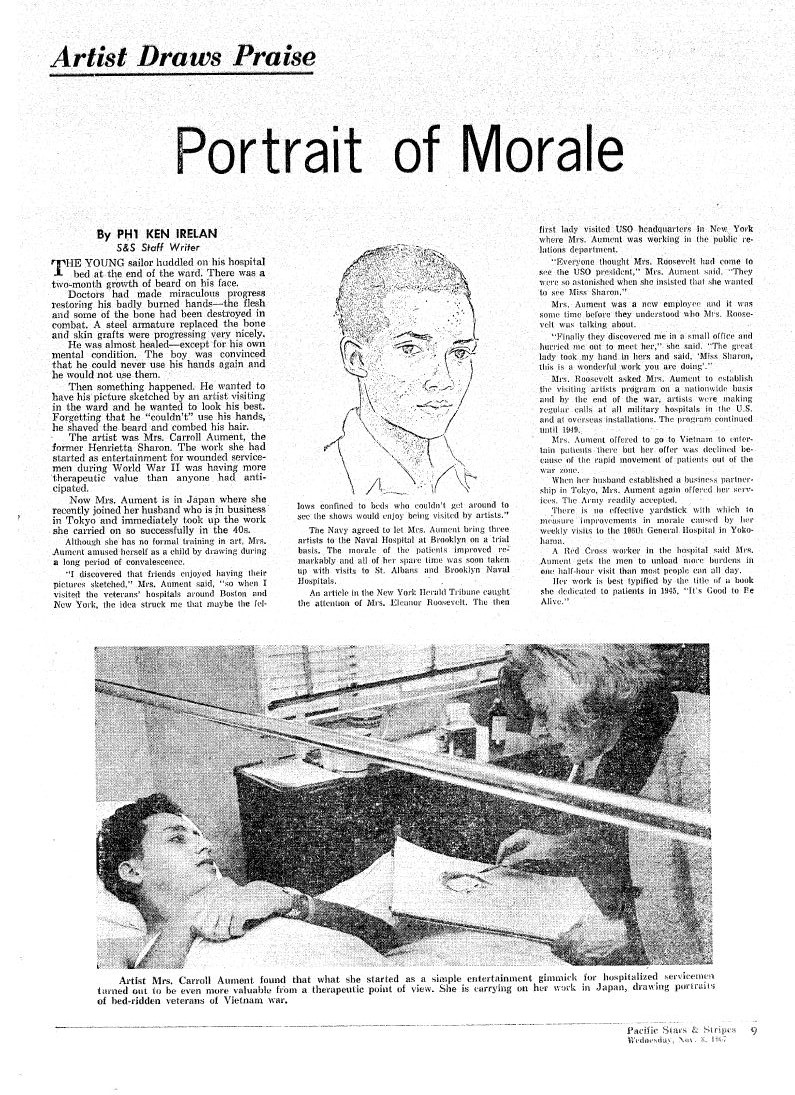

The 106th General Hospital in the Pacific Stars and Stripes

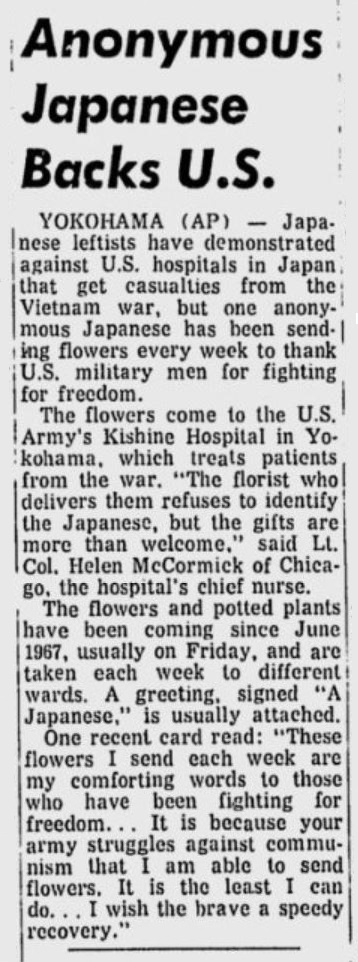

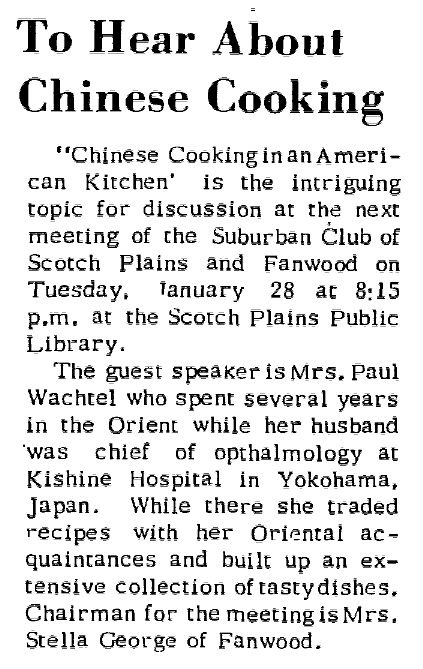

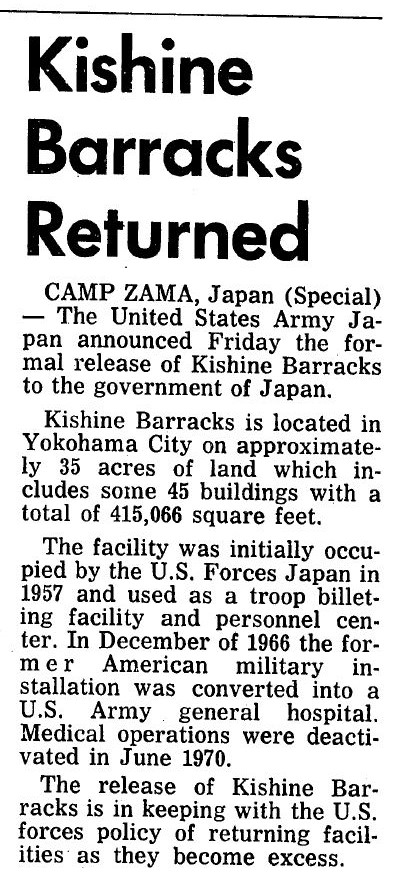

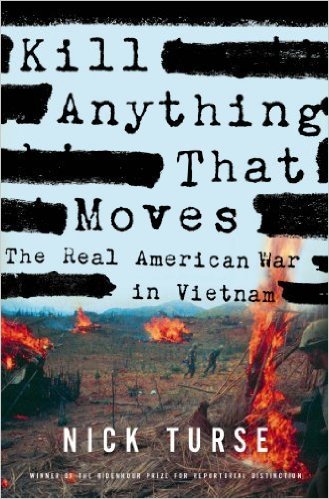

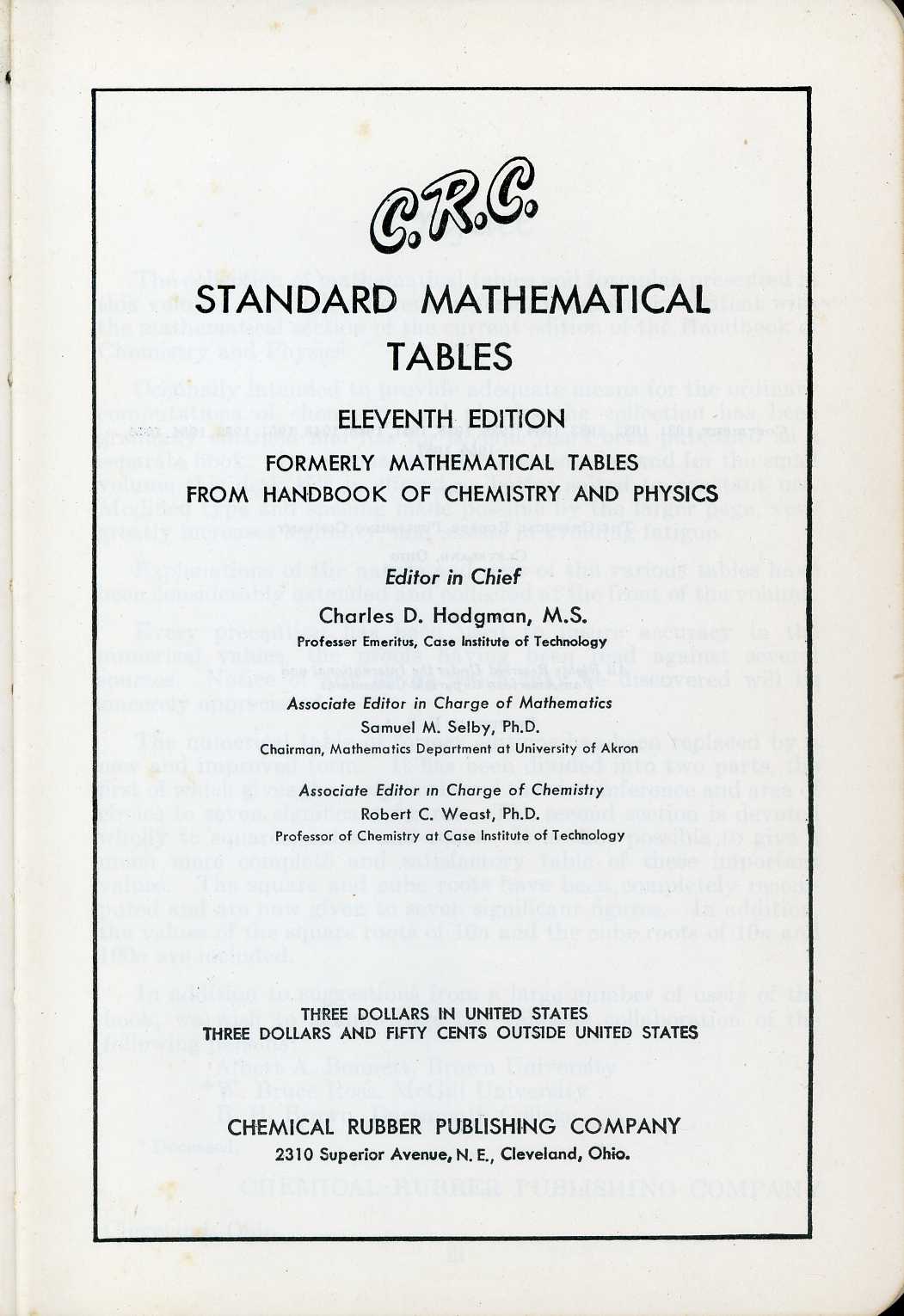

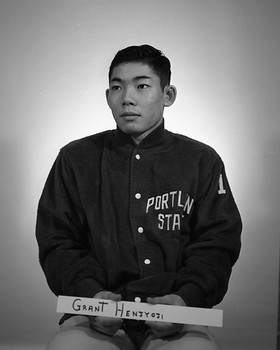

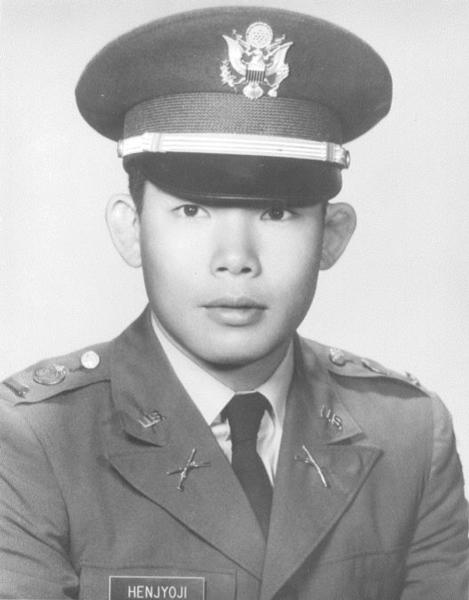

The Pacific Stars and Stripes is the most logical source of reports about Kishine Barracks the 106th General Hospital during its deployment there. I have integrated reports about Kishine Barracks -- from its start in 1957 to the arrival of the 106th General Hospital in 1965, and from the departure of the 106th in 1970 to the reversion of Kishine Barracks to Japan in 1972 -- in the "History of Kishine Barracks" section (below). Here I have organized selected clippings of reports about the 106th under several broad categories that taken together seem to cover all the "bases" as it were.